Caroline Louise Ransom Randolph Williams, daughter of John and Ella Randolph Ransom, was born on February 24, 1872 in Toledo, Ohio. She was born during the early stages of women gaining their voice and power in the United States which would greatly define how accomplished of a scholar she truly was. She first attended local Erie College until her aunt, Louise Fitz-Randolph, who a professor of art history at Mount Holyoke College, convinced her parents to attend Mount Holyoke.

Caroline Louise Ransom Randolph Williams, daughter of John and Ella Randolph Ransom, was born on February 24, 1872 in Toledo, Ohio. She was born during the early stages of women gaining their voice and power in the United States which would greatly define how accomplished of a scholar she truly was. She first attended local Erie College until her aunt, Louise Fitz-Randolph, who a professor of art history at Mount Holyoke College, convinced her parents to attend Mount Holyoke.

She graduated in 1896, the year the Supreme Court ruled “separate but equal” legal. She accompanied her aunt on a grand tour of Europe and Egypt where she fell in love with antiquities. At the time, Egyptology had just become a degree program at the University of Chicago. Chicago was a new coeducational school that easily connected to her home in Toledo by train. She taught at Erie College for a year and then began her graduate studies at the University of Chicago in 1898 under Professor James Henry Breasted. In 1900, she received an AM in classical archaeology and Egyptology and was regarded by Breasted as a promising scholar. He encouraged her to continue studying abroad and with his strong recommendation, she was accepted as a student in Berlin and was a student of Professor Adolf Erman. She was one of the first women in continental Europe to study Egyptology at a university. She was given an assistanceship position in the Egyptian Department of the University of Berlin in 1903, but decided to return to Chicago.

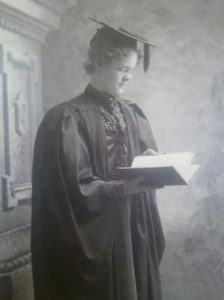

She returned to Chicago to write her doctoral dissertation which was later published and in 1905, she was rewarded a Ph.D. and was the first American woman to receive an advanced degree in Egyptology. Her dissertation was later published as “Studies in Ancient Furniture.” Although she had a suitor at home, Caroline decided to focus on her career and stayed single. That fall, she became an Assistant Professor in the Department of Archaeology and Art and eventually became the head of the department. Both these achievements were great feats because one of the biggest challenges for pioneer-generation women in archaeology was male chauvinism which made men incapable of accepting authority of women. And in publishing, women were often refused by male establishments.

In 1910, she accepted an appointment as Assistant Curator in the Department of Egyptian Art of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. During her time there, the Metropolitan allowed her some time to return to Germany to further her research which was about the time of the beginnings of World War I. During her stay in Germany, she worked on her research as well as helped her aunt, Louise Fitz-Randolph, examine various casts to be added to Mount Holyoke College’s Collection. Due to the war, the Metropolitan Museum put a temporary halt to its overseas operations and made some cut backs in staff. It is unclear whether she returned on her own accord or was let go, but it was then when she returned to Toledo in 1916 and accepted the proposal of Grant Williams.

She had many jobs studying Egyptian collections at museums, and some of them overlapped. In 1916-1917, She spend time studying the small Egyptian collection at the Cleveland Museum of Art and the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. In 1918, she became honorary curator of the Egyptian collection at the Toledo Museum of Art while in 1917, she was offered the curatorship of the Egyptian Collection of the New York Historical Society. She was asked to prepare a scientific catalogue of the thousands of Egyptian objects of the Abbott Collection, a task which women then and now are most often assigned. This whole collection was purchased by the New York Historical Society.

Caroline Ransom was later elected to be a life member of the New York Historical Society in appreciation of her work for them. Acknowledgement of her help was often mentioned in many publications that she helped with which was an uncommon occurrence for women of those times. Of the publications that she had helped with, she identified a papyrus scroll in the Society’s collection which Breasted later published a piece on. This scroll was the Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus.

While she was in her fifties, around when women were given the right to vote, she accepted an offer by her former professor and mentor Breasted to become a member of his fledgling Epigraphic Survey in Egypt. The subsequent directors had many reservations about including a woman as a member of this staff, a problem many early women archaeologists faced. She was mentioned in the records of Breasted as well as others which was a time when women were not often referenced in histories of archaeology or biographies. He described her as one of his “ablest students.” In 1926-1924, she worked as an epigrapher in Egypt for the Oriental Institute at the mortuary temple of Ramses III. She worked in Cairo, Egypt again in 1935-36 for the Coffin Texts project at the Egyptian Museum.

Between her jobs away from home, Caroline represented the state of Ohio on Ohio Day at the Sesquicentennial Celebration in Philadelphia and taught Egyptian art and the Middle Egyptian phase of the ancient language at the University of Michigan. She was the first person to teach those courses at that university. She was elected president of the Mid-West Branch of the American Oriental Society in 1929, becoming the first woman to hold office in that organization. She was also a member of many Egyptological and archaeological societies such as the Archaeological Institute of America as well as the German Institute.

On Christmas Eve of 1942, she lost her husband, Grant, after a long illness. She became very ill later, but soon after recovering, she donated her collection of Egyptian antiquities to Mount Holyoke College in 1943. She moved into Toledo’s Park Lane Hotel which was the address she gave to the “Directory of American Scholars” to whom she lists her career interests as both Classical Archaeology and then Egyptology.

Caroline Louise Ransom Williams lived as a widow for 10 years in Toledo. She died on February 1, 1952 after being ill for a week. It is clear that she was a woman who dedicated her life to her love and passion for education. She set herself apart from the conventional woman of her time and broke through many barriers to get to the place of recognition in which she was at. She was a woman of wit and sarcasm who hated questionnaires and had no problem expressing how they bore her and that she feels they are a waste of time. She is remembered for her devotion to “family, church, each Alma Mater, to friends in all walks of life at home and abroad.”