As a student and teacher at Mount Holyoke, Cornelia Clapp had studied William Smellie’s Philosophy of Natural History, but her summer at the Anderson School of Natural History on the island of Penikese in Buzzards Bay, Massachusetts was the first time she really learned to study nature itself. Decades later, she described the experience as “an opening of doors,” the moment when she entered the biological world.

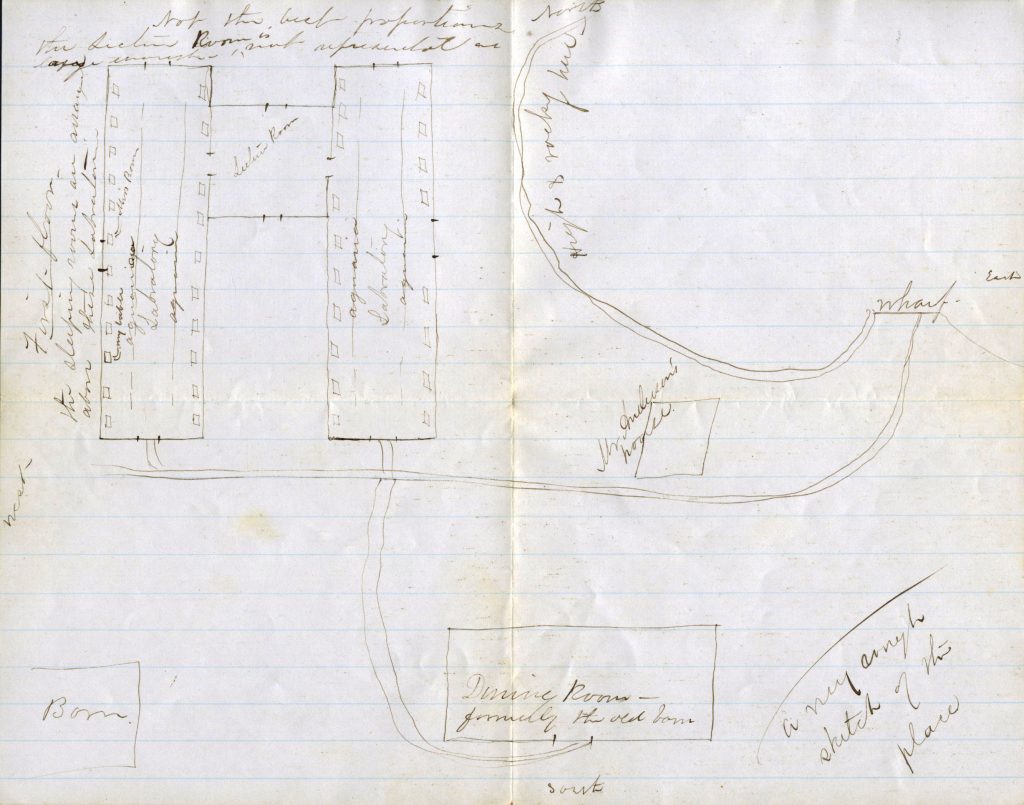

In her first letter home that summer, Clapp included this “rough sketch” along with her enthusiastic account of her experience so far. She marked her work table in the laboratory, the lecture room where the “real, genuine old German drawing teacher” gave her an impromptu lesson on scientific illustration, and the rocky shore where she went to watch the glow of the jellyfish that she had only read about before.

Clapp “became a fish woman” on her first summer tramp with David Starr Jordan, an ichthyologist she knew from Penikese, and his party in 1878. She had spent a few summers collecting specimens when Jordan decided he would take a party of students and friends on a collecting trip on foot across the American South.

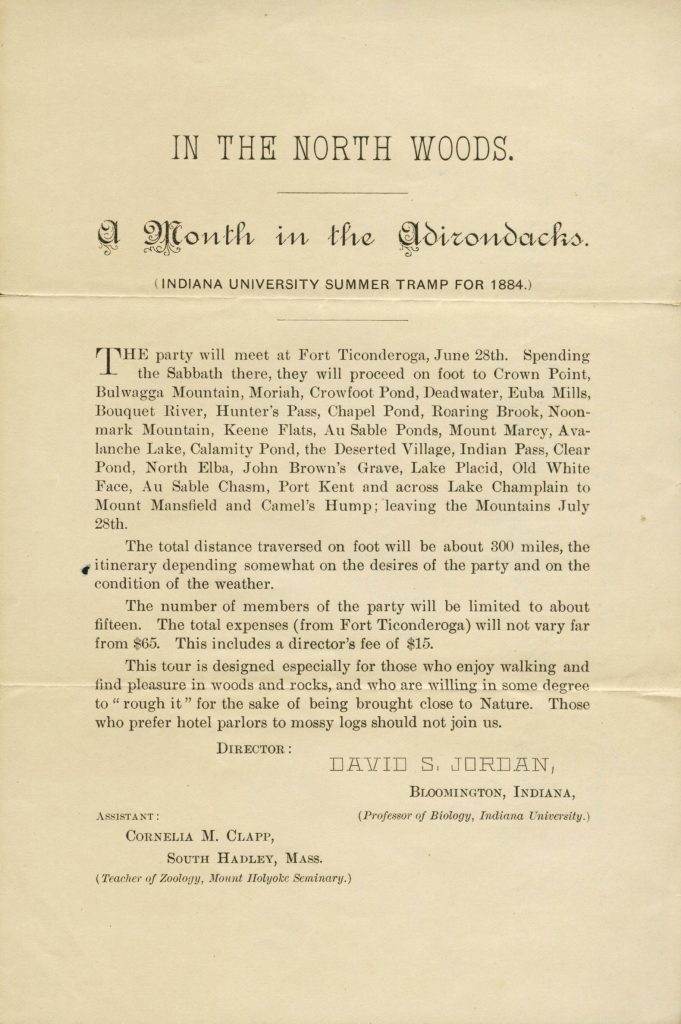

For most of the next decade, Clapp spent her summers in this party of “tramps,” traveling on foot across different regions of the U.S. and Europe to observe and collect animal specimens. While she helped Jordan coordinate most of these tramps, this was one of the few trips where she was formally listed as an assistant.

Clapp was ready for the Marine Biology Laboratory at Woods Hole, Massachusetts, before the lab was ready for her: when she arrived, it was still under construction! Soon after, though, the tables were all built and the work of the first summer could begin.

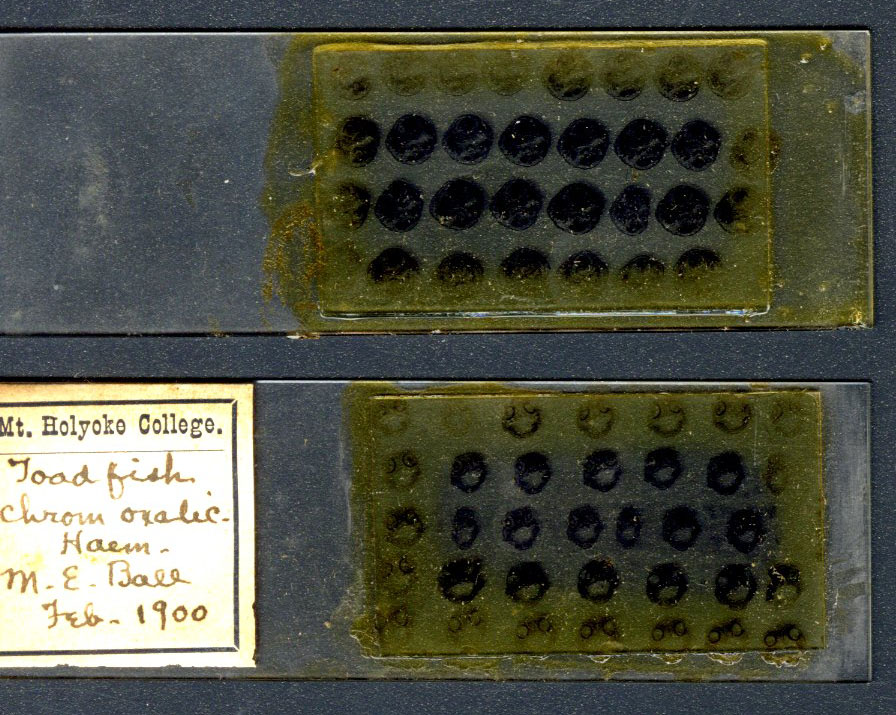

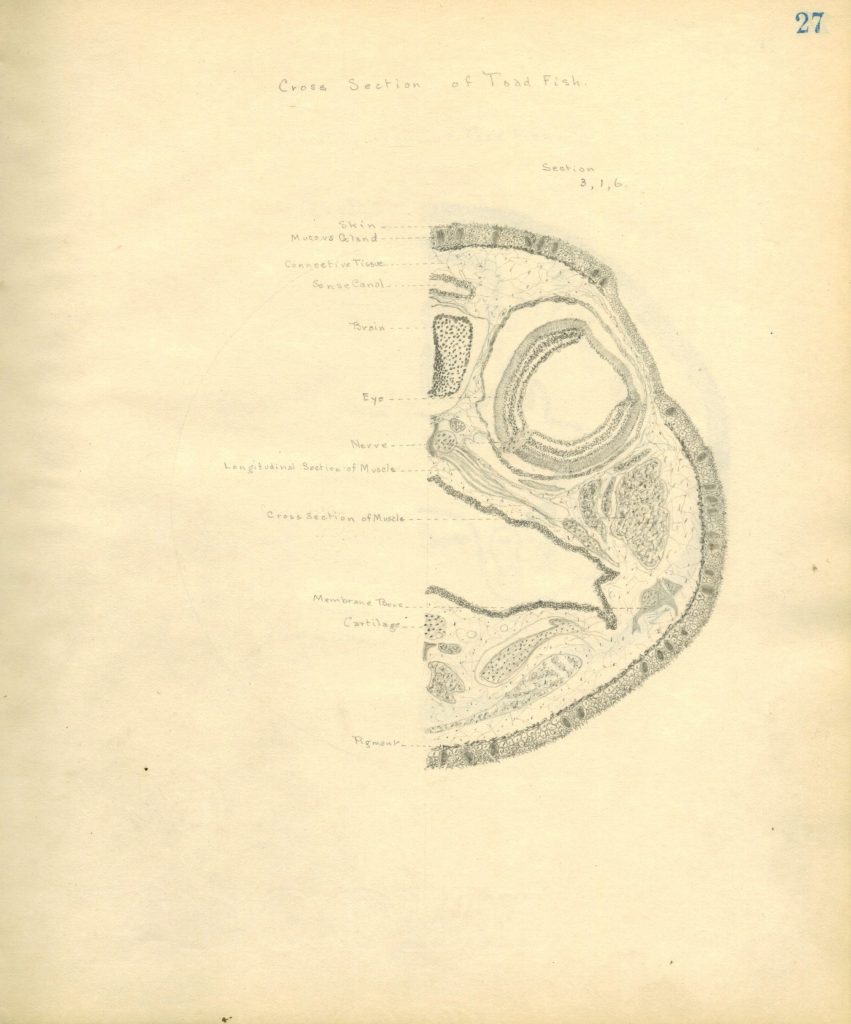

Clapp, now nearly 15 years into her whole-hearted embrace of zoological inquiry, received the very first research problem assigned at Woods Hole: she was going to study the toadfish and try to understand its lateral line. When this photograph was taken in 1893, she was still working steadily on the toadfish and its senses.

What is a lateral line? Clapp and her contemporaries weren’t sure. By 1888, when Clapp started her research, most scientists agreed that the lateral lines of fish sensed something, but most of them assumed that they helped the main sense organs detect either sound or touch.

From her close observations, however, Clapp disagreed, suggesting that the lateral line was actually its own specialized sensory system – and she was correct! In the mid-20th century, scientists confirmed that fish have a specific “lateral line sense” for movement and pressure that is distinct from the other senses.

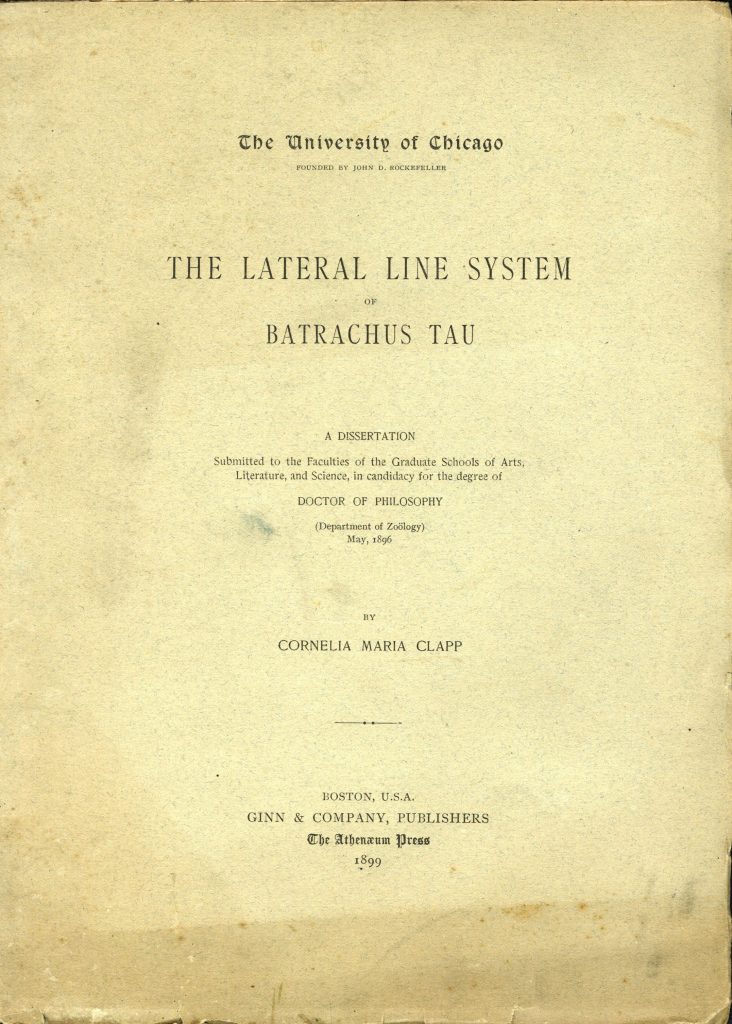

Clapp earned her second Ph.D. in 1896, making her the first American woman to hold two doctorates in the same subject area, and the only woman to do so in the 19th century.

She earned her first Ph.D. from Syracuse University in 1889. She did so based on an examination and the work of her first summer at Woods Hole. Likely wanting a more dedicated research degree, she elected to take a leave from Mount Holyoke to study the toadfish full-time for a Ph.D at the University of Chicago from 1893 to 1896.

“There is,” Clapp’s doctoral thesis began, “something singularly grotesque in the appearance of the toadfish.” Despite her harsh assessment of its appearance, it’s hard to imagine anyone appreciating the toadfish more than Clapp. In countless minds, she was forever tied to the creature she studied. For decades, Opsanus tau was known at Woods Hole as “Dr. Clapp’s fish,” and it was best known at Mount Holyoke for its starring role under the microscope in her histology class.

Clapp always referred to her fish as either “the toadfish” or Batrachus tau, but there are close to a hundred different species of toadfish, and Batrachus tau is no longer considered a valid species name. Luckily, her descriptions clearly indicate that the species she studied was the oyster toadfish, Opsanus tau, which is common near Woods Hole.

“During the summer of ’91,” Clapp explained at a talk in 1893, “the fascinations of embryology held me captive.” Then later she began studying how the lateral line developed in relation to the rest of the individual toadfish embryo, and she quickly learned that her subject was especially well suited to this line of study: its eggs were large, transparent, and fixed in place, which made observing each embryo’s development easier.

This paper, which was printed in the Journal of Morphology later that year, was the first of her two scientific publications, both discussing the toadfish.

By the 1910s, Clapp was one of the only figures at the Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL) who had attended since that first summer in 1888. She was a continuous presence for nearly 50 years, and she carried the spirit of the “Old Guard” at the MBL with her commitment to collaboration, education, and genuine wonder for generations of Woods Hole scientists.

After 23 years as a pillar of the MBL, Clapp was elected to the Board of Trustees. She was the only woman to be granted this level of recognition and influence at Woods Hole from her appointment in 1910 until well after her death in 1934, and she used her unique position to ensure that the laboratory remained open to women when many scientific institutions did not.

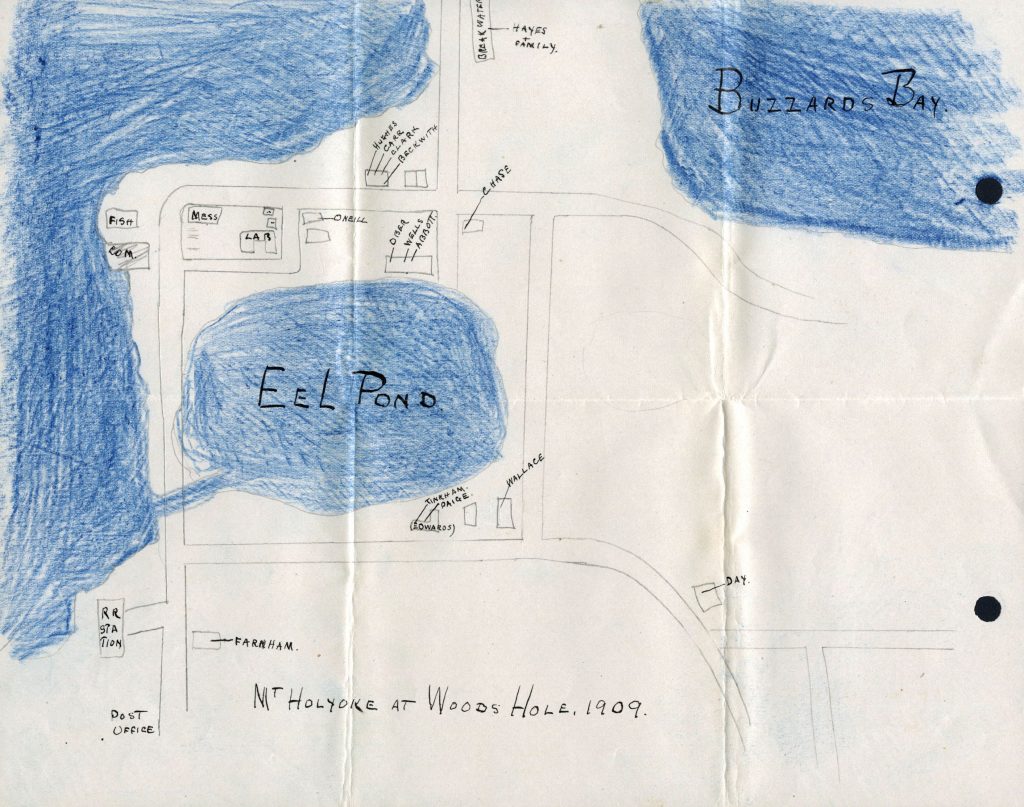

Clapp initiated an ongoing connection between Woods Hole and Mount Holyoke. Every name on this map refers to an MHC student, faculty member, or alumna who went to Woods Hole either to teach, to take classes, or to conduct research.

In 1917, the year after she retired from Mount Holyoke, Clapp built herself a permanent home in Woods Hole, which she named Pine Knot. Every summer until she passed, she stayed there, invited guests, and hosted whoever she could for gatherings and stays ranging from a weekend to a month.

In an obituary, Clapp’s friend Louise Baird Wallace wrote of her, “one needed an overcoat less in passing her house;” her cottage among the trees was a source of warmth for anyone who came by, and Clapp made sure that many people did.

After she retired, Clapp lived with her sisters Harriet, x-class of 1876, and Mary, x-class of 1880, in Mount Dora, Florida for most of the year, delighting in the much milder winters than they were used to in New England.