While she was a student at Mount Holyoke Female Seminary, Cornelia Maria Clapp, class of 1871, had learned about animal life in a class called “Smellie’s Philosophy of Natural History.” As a teacher, though, she quickly transformed the study of a single natural history text into an entirely new course in zoology.

In 1874, after less than two years teaching Smellie, she spent her summer outside and in the laboratory on the small island of Penikese in Buzzards Bay, Massachusetts. There, she and her fellow teachers and scholars learned how to see and learn about the natural world for themselves. She committed herself to helping her own students “study nature, not books,” to be curious about the world around them and to develop the ability to ask and answer questions about animal life.

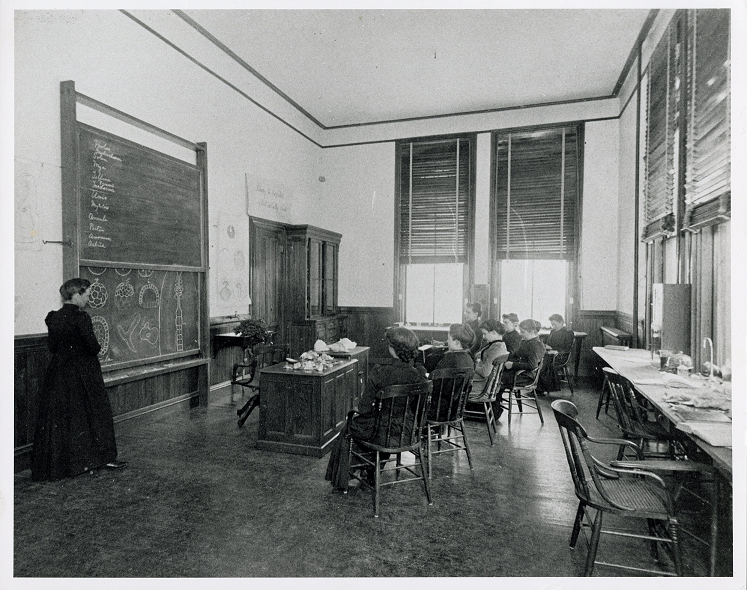

Under Clapp’s direction, the single laboratory class in zoology at the Seminary grew into a robust and extensive department. She expanded and adapted her courses to follow the zoological field as a whole, introducing subjects like embryology, neurology, and heredity as biologists’ collective attention shifted to each new area. By her retirement in 1916, Clapp’s department rivaled the undergraduate offerings of most men’s colleges and universities in the country.

Outside of Mount Holyoke, Cornelia Clapp maintained her lively spirit, her commitment to scientific thought, and her investments in her communities. After her entrance into the world of biological research on the island of Penikese in Buzzards Bay, Massachusetts in 1874, Clapp returned to her zoology research work each summer, first on collecting trips and then, from 1888 onward, at the Marine Biological Laboratory at Woods Hole, Mass.

At a time when women were rarely included in the biological sciences, Clapp was able to publish articles and earn two doctoral degrees using her research on the toadfish from Woods Hole. When she retired from teaching at Mount Holyoke in 1916, Clapp continued to spend her summers at Woods Hole, using her influence to ensure that the research opportunities she had benefited from remained open to other women going forward. She spent the rest of each year in Mount Dora, Florida, where she and her younger sisters Harriet Clapp, x-class of 1876, and Mary Clapp, x-class of 1880, lived together. Cornelia Clapp made the round trip between Massachusetts and Florida every year until she passed December 31, 1934.

Following in Cornelia Clapp’s legacy, three women developed the department that she founded at Mount Holyoke into one of the best programs for zoology in the world. Ann Haven Morgan, A. Elizabeth Adams, class of 1914, and Christianna Smith, class of 1915, were the core faculty of the department from Clapp’s 1916 retirement until the late 1940s, and they each combined their unique strengths and research areas with the central values they learned from Clapp as a teacher, mentor, and colleague. Adams and Smith both took classes with Clapp when they were students before working with her as zoology assistants. While Morgan was not a Mount Holyoke alumna, Clapp was the head of zoology for Morgan’s first decade at the College, and remained a mentor and a close friend to all of them for decades after retiring.

With Morgan’s work in ecology, Adams’ in endocrinology, and Smith’s in histology, each woman broke new ground in both scientific research and college instruction in three of the most active fields of zoological study at the time. Their extensive research work cemented them all as influential figures in their fields. The courses they developed for their subjects, which followed Clapp’s emphasis on laboratory methods, meant that Mount Holyoke had one of the most extensive and in-depth undergraduate programs in zoology in the country. When they started offering graduate work in the late 1920s, they offered one of the strongest master’s programs in the U.S. as well. They also continued Clapp’s commitments beyond the classroom. By exclusively employing women in the department and coauthoring many research publications with students in the master’s program, they provided opportunities for dozens of women in an academic field with very few positions open to them.

Morgan, Adams, and Smith, like Clapp before them, encouraged young women to pursue advanced degrees in zoology, maintained a strong connection to major research institutions, and held prominent positions in the broader biological world without wavering in their deep commitments to Mount Holyoke and its students.

The Cornelia Clapp sections were curated by Becca Moses ‘24.