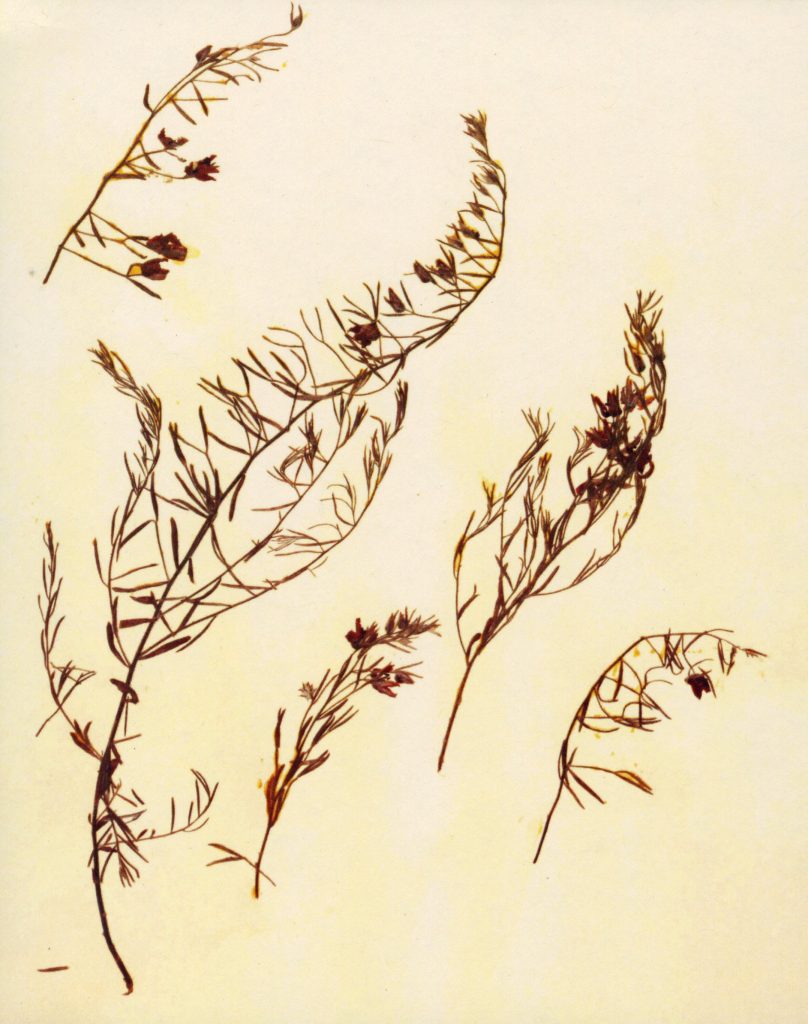

Making herbariums is one of the earliest traditions at Mount Holyoke College. Until 1856, the Seminary required students to identify and preserve at least 300 species of plants per herbarium.

The College changed its requirements in 1897. Herbariums were now elective for students not studying botany. So, why did students continue making herbariums at Mount Holyoke?

“The immediate aim of the department is to give a knowledge of the structure, behavior, and distribution of plants. The ultimate aim is to inculcate scientific method and attitude.” – Alma G. Stokey (department head and professor of botany), Mount Holyoke Alumnae Quarterly, July 1921

“At an earlier period, botany was not a practical science or a subject for any type of serious and exacting study, but an aesthetic exercise. As Dr. Coulter has expressed it, “Botany was an emotion, not a science.” Accordingly, he believed that the study of plant science was most appropriate for women “for the delicacy of the female mind,” on the ground that “‘all is elegance and delight.'” – Alma G. Stokey

Instructors at Mount Holyoke disagreed with this idea: “at the present day our delight in botany is derived from a set of mental processes entirely different from those which were regarded a century ago as the only suitable ones for the ‘female mind.’” – Alma G. Stokey

“We have students coming into our classes who represent in a measure these two widely different points of view of the nature of botany. To some it is a serious disappointment that botany makes other demands than a love of flowers, to others it is a disappointment that its first work is not the training of gardeners, but there are many who find great stimulation and even “romance,” as one student expressed it, in the revelation of the unexpected variety and complexity of the problems of the plant world.” – Alma G. Stokey

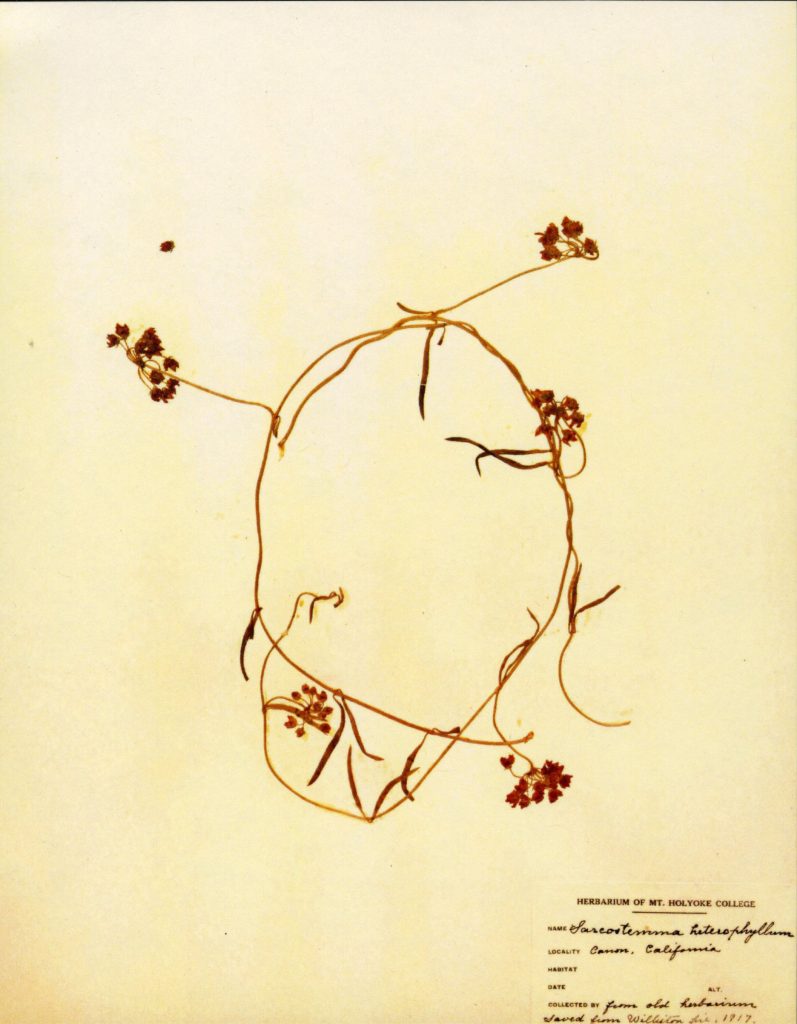

Though the 1917 Williston fire caused irreversible damage to the school’s scientific collections, not all hope was lost. The below preserved milkweed is likely one of the few surviving pages from the herbarium that students pulled from the rubble.

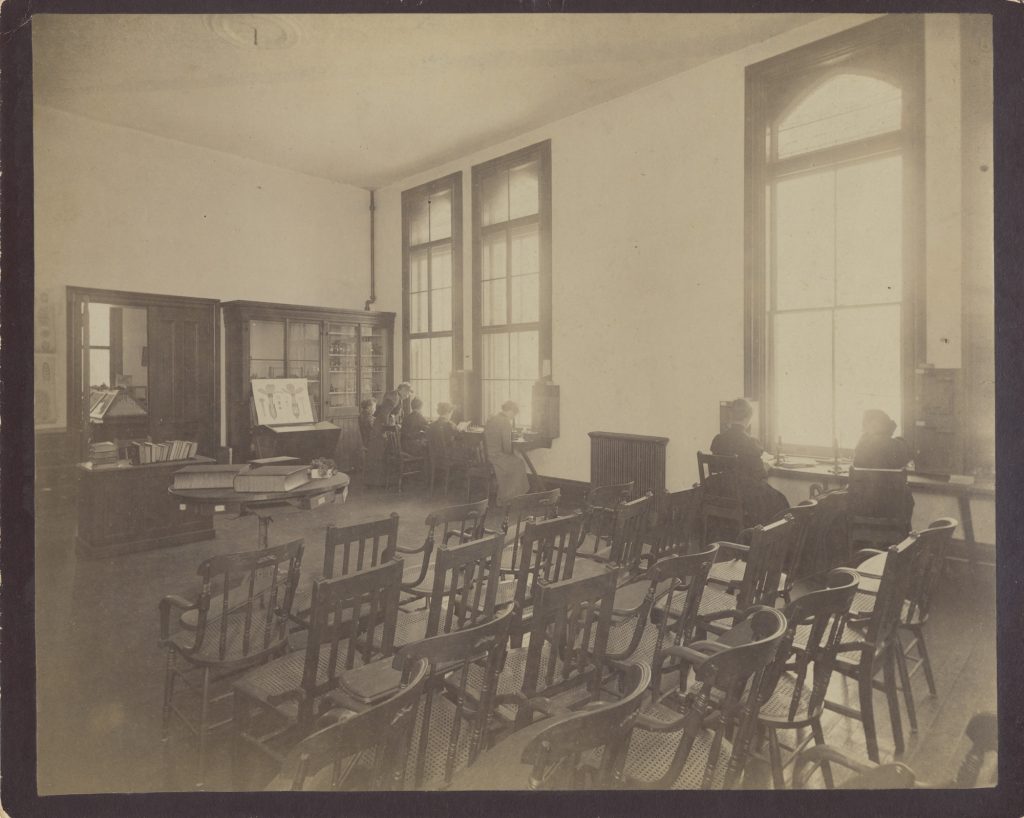

Once the ashes settled, students and faculty alike began to rebuild the herbarium collection. The easiest place to start was right at home.

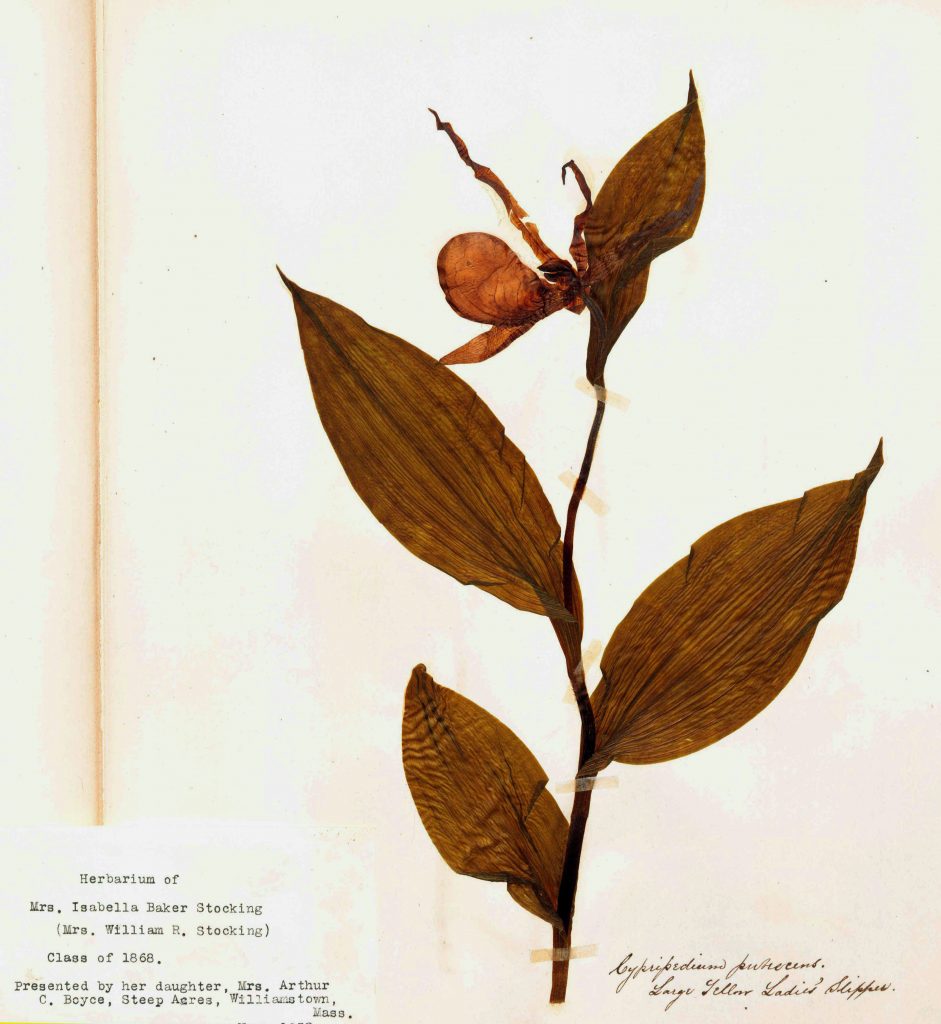

As the unveiling of the new Cornelia Clapp Laboratory continued, so did efforts to rebuild the herbarium. The College continued to accept donations, including this page, from alumnae, former faculty, and others interested in supporting its development.

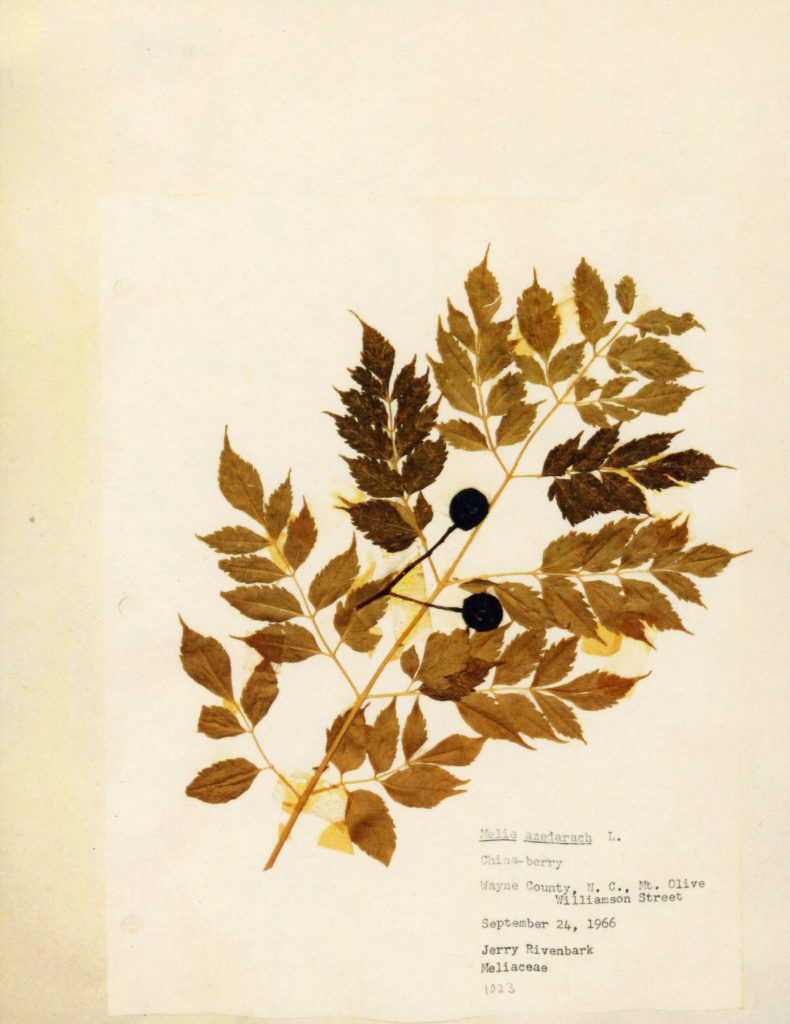

In 1964, the botany department ceased to exist. Instead, it became a part of the newly minted department of biological sciences. At the same time, the College invested resources into new laboratory equipment. By this time herbariums were now considered an outdated method of teaching plant science. After 1964, few students continued to make herbariums.

The new department of biological sciences brought together previously separate classes, people, and specimens. The boundaries between these groups blurred as professors shared classrooms and storage space. The below shell comes from Stan Rachooton, a professor emeritus of biological sciences. His collection contains shells, wet specimens, and fossils. This object is stored in a cabinet only a few feet down the hall from the herbarium collection in Clapp.

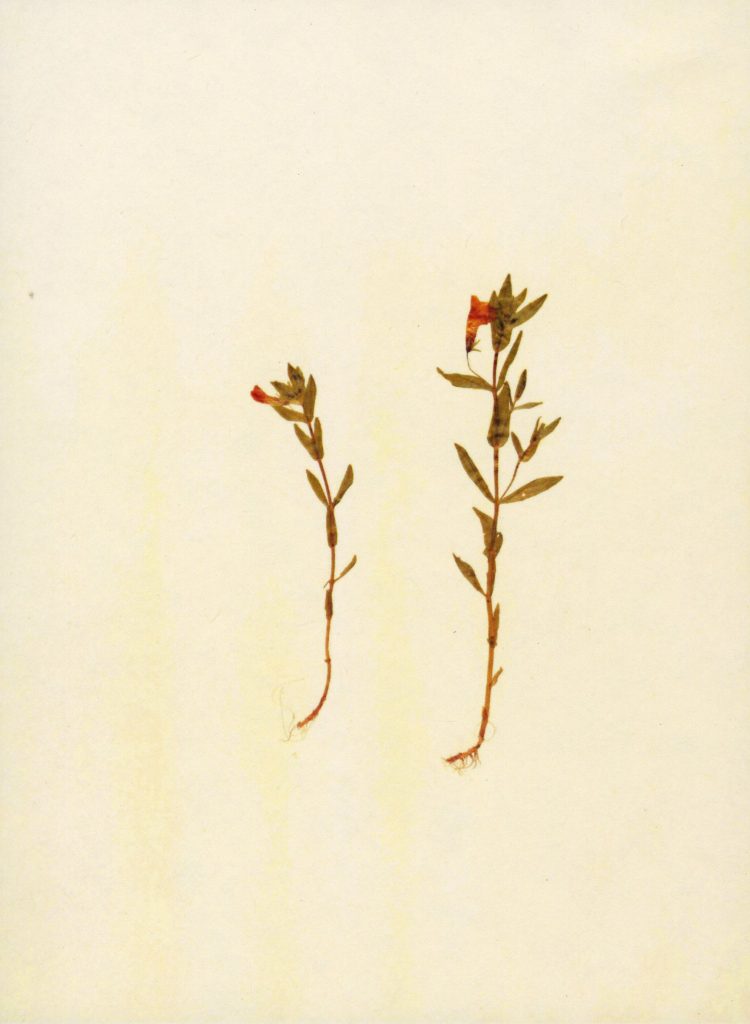

As of the early 2000s, the tradition of making herbariums at Mount Holyoke College has almost completely died out. The below page from 2001 is one of the most recent specimens in the College’s collection.