Cornelia Clapp first learned what it meant to “study nature, not books” at the Anderson School of Natural History on the small island of Penikese in Buzzards Bay, Massachusetts during the summer of 1874. By 1876, she turned the course in “Smellie’s Philosophy of Natural History” into simply “Zoology,” replacing the textbook with a laboratory course where her students learned by observing animal specimens directly. When she wrote a summary of this change at the end of the decade, her students could consult an impressive library of books to help clarify, classify, and interpret what they saw, but the textbook was gone for good.

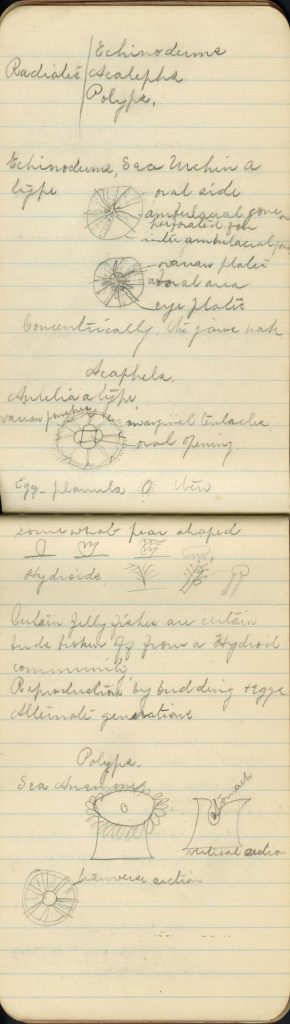

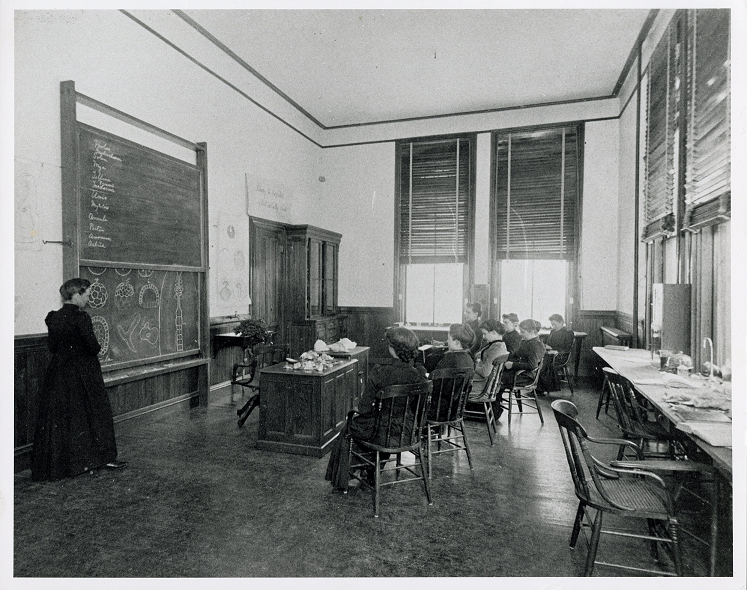

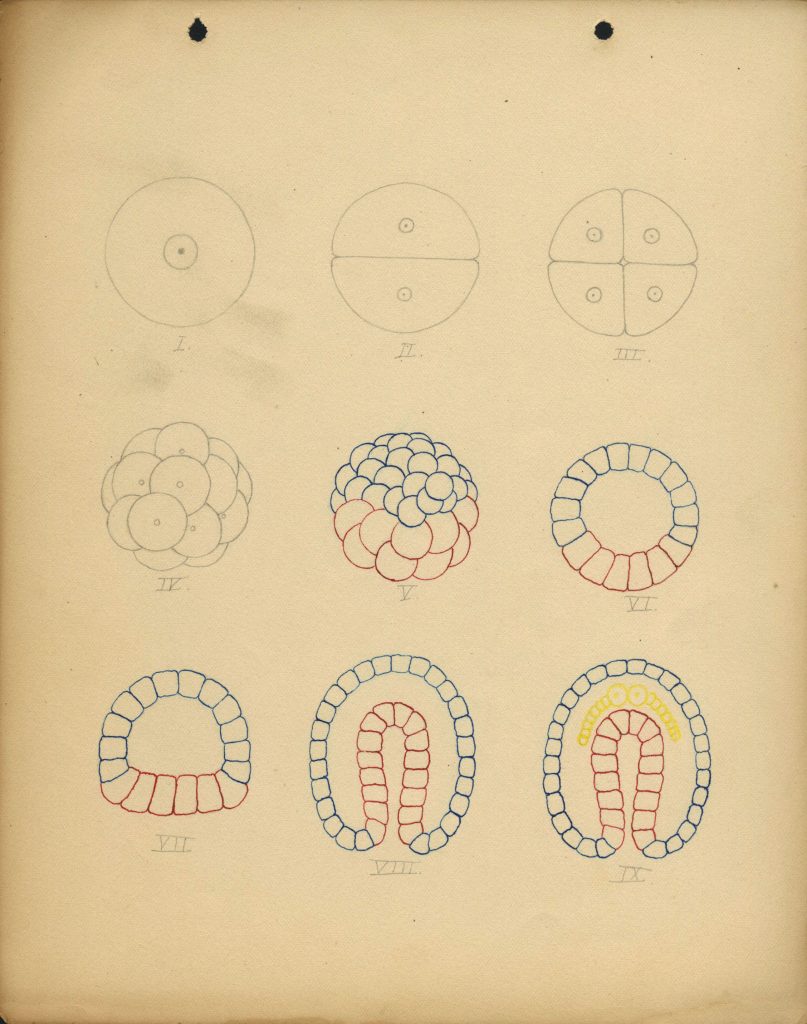

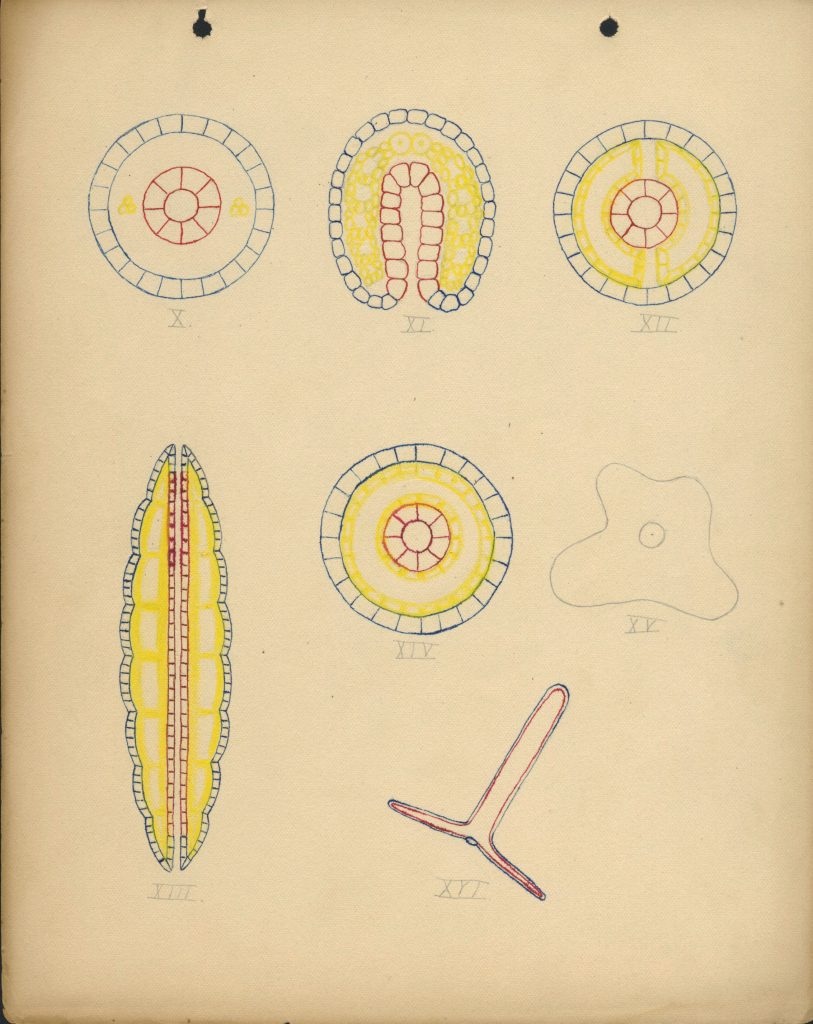

The drawings on the blackboard behind Professor Clapp show the same process as the pages of the notebook by Ella Farrington, class of 1899: the development of a single cell into an adult earthworm.

The earthworm was one of Clapp’s most important means of helping students learn how to actually do zoology: she wanted them to be curious and careful, to make observations for themselves, and to learn from what they saw. By drawing connections between its embryological structures and its adult form, her students learned how to make new meaning by looking at the natural world in new ways.

In 1874, Clapp knew that observation was a better teacher than any book or lecture, so she decided that her class should dissect a cat. Her classroom was dark and cramped, but that didn’t stop her. During the first year, her students dissected a cat on a second-story veranda of the Seminary building overlooking College Street.

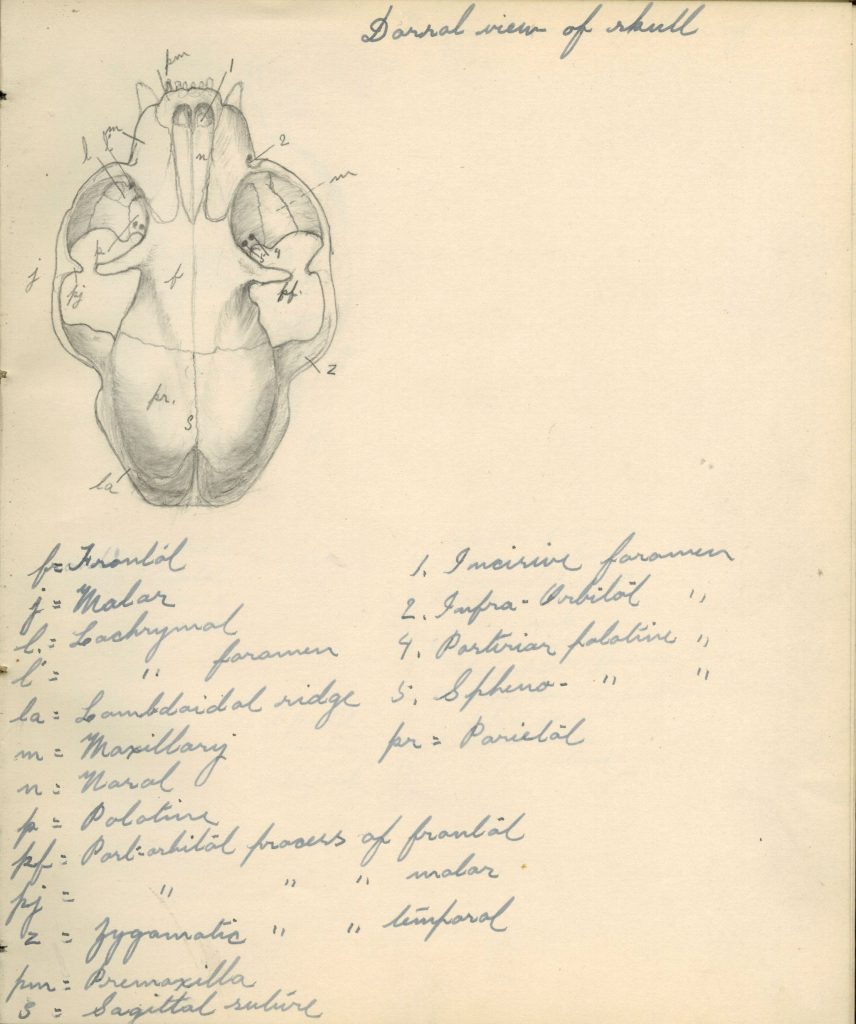

Nearly all of Clapp’s students participated in at least one cat dissection, but Mary Phylinda Dole, class of 1886 (BA) and 1889 (BS), went beyond that standard. At Clapp’s suggestion, she took on a close study of mammalian physiology using the cat as a typical species. She became the first person to mount a skeleton at Mount Holyoke, and “Dr. Dole’s cat” became an important part of the zoology teaching collections.

The skeleton was lost in the 1917 fire in Williston Hall, but her notebook – and the notebooks of many students who used the skeleton as a reference in their own drawings – continue to show the significance of her work.

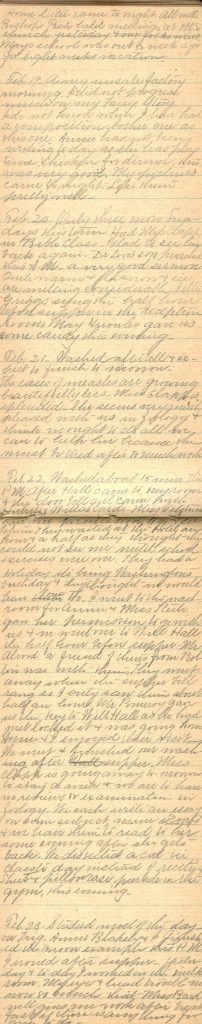

The diary entries of Harriet Tracy, x-class of 1883, from winter 1881 frequently mentioned “Miss Clapp,” who taught Bible class as well as zoology. These pages from the end of the term discuss Clapp’s time away from campus and the structure of the final classes and assignments in zoology.

“Feb 20 … Had Miss Clapp in Bible Class. Glad to see her back again…”

“Feb 21 … Miss Clapp is splendid. She seems very much pleased with us in Zoology + I think we ought to do all we can to help her because she must be tired after so much work.”

“Feb 22 … Miss Clapp is going away to-morrow to stay a week + we are to have no reviews or examination in Zoology. We each write an essay on some subject, mine is “crabs” + we have them to read to her some evening after she gets back. We dissected a cat in class to-day instead of reciting.”

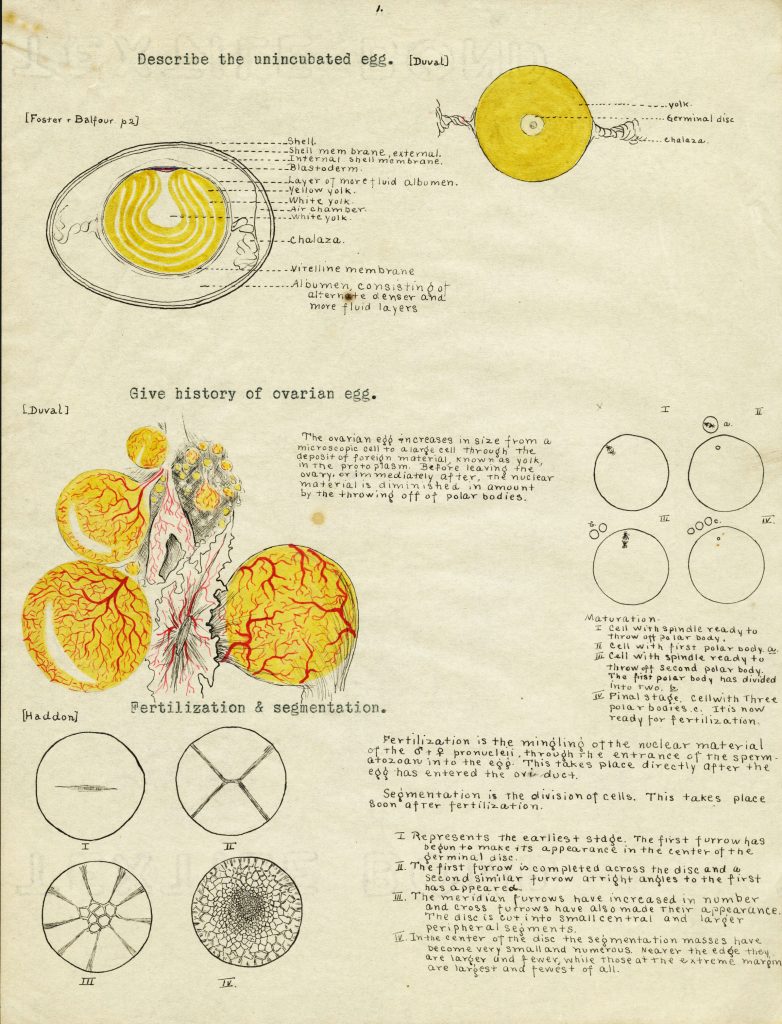

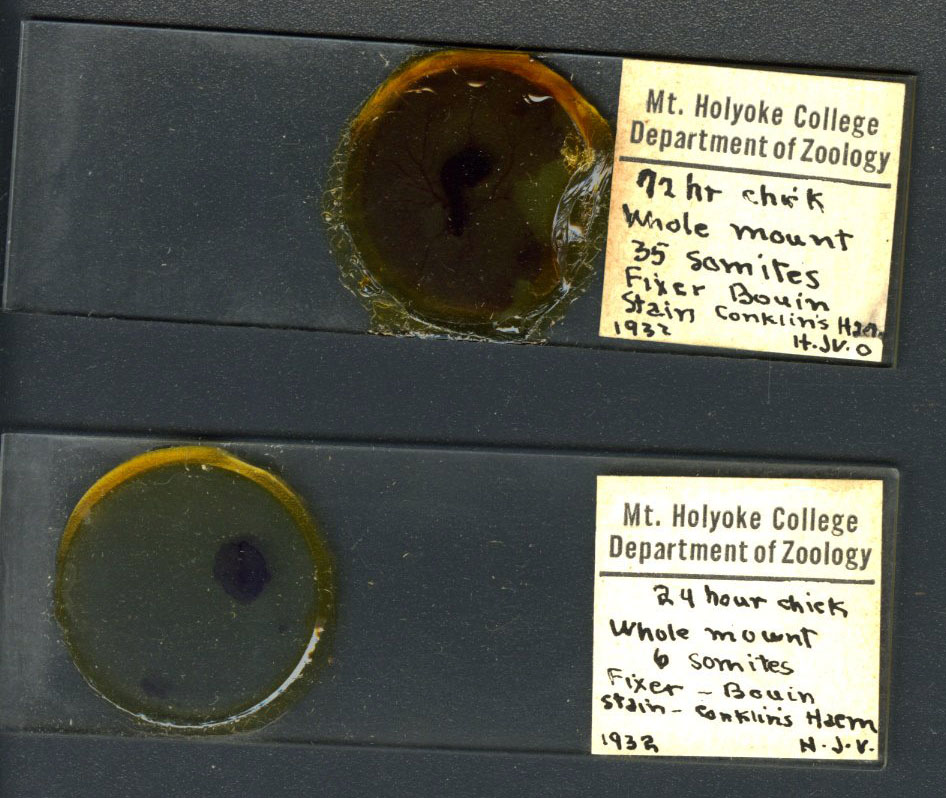

Cornelia Clapp introduced embryology to Mount Holyoke with the help of a chicken. One year in the 1870s, she rented a hen for a month, putting a new egg underneath it every day for 28 days. By the end of the month, she had a series of 28 embryos in 28 stages of development to display.

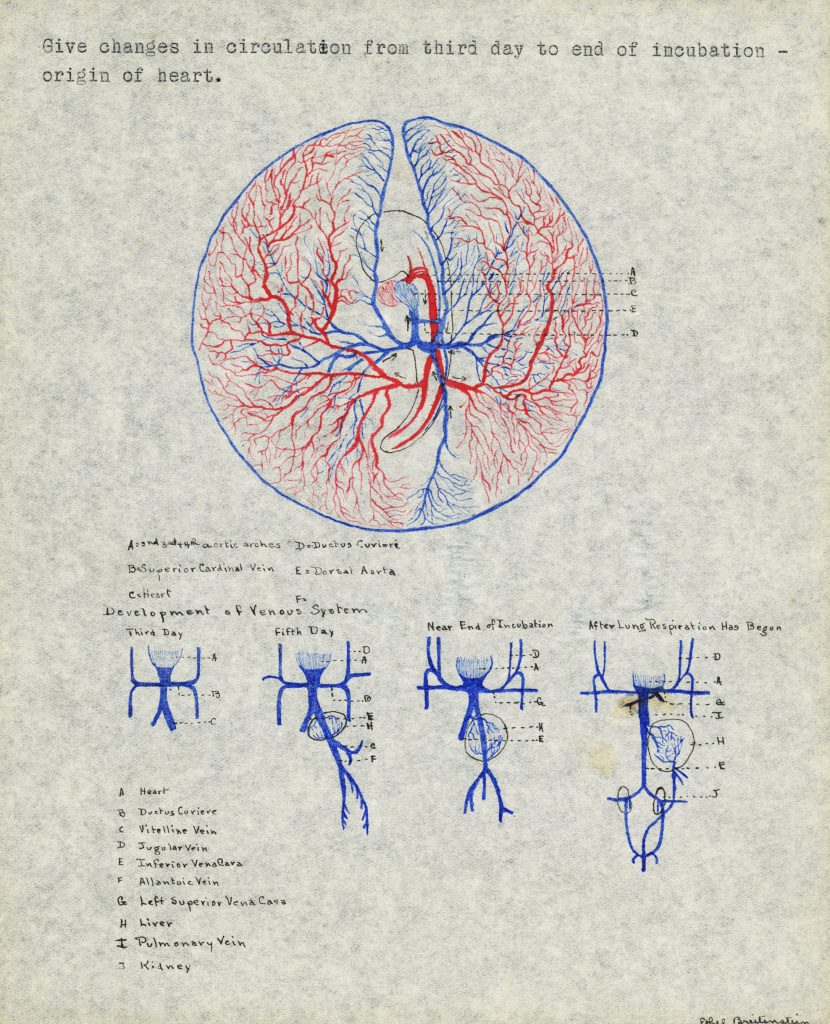

This experiment marked the first venture into embryology at Mount Holyoke, but not the last. In 1884, when faculty began to offer multiple courses in each subject, chick embryology was a central focus for advanced zoology work. From then on, Clapp taught a course in vertebrate embryology with chicks every year until her retirement in 1916. Similar courses would be offered every year until 1979, and the embryology of the chick is still part of the curriculum for biology students today, nearly 150 years after Clapp’s first experiment.

Embryology finals required students to draw and explain different elements and stages of the chick’s development.

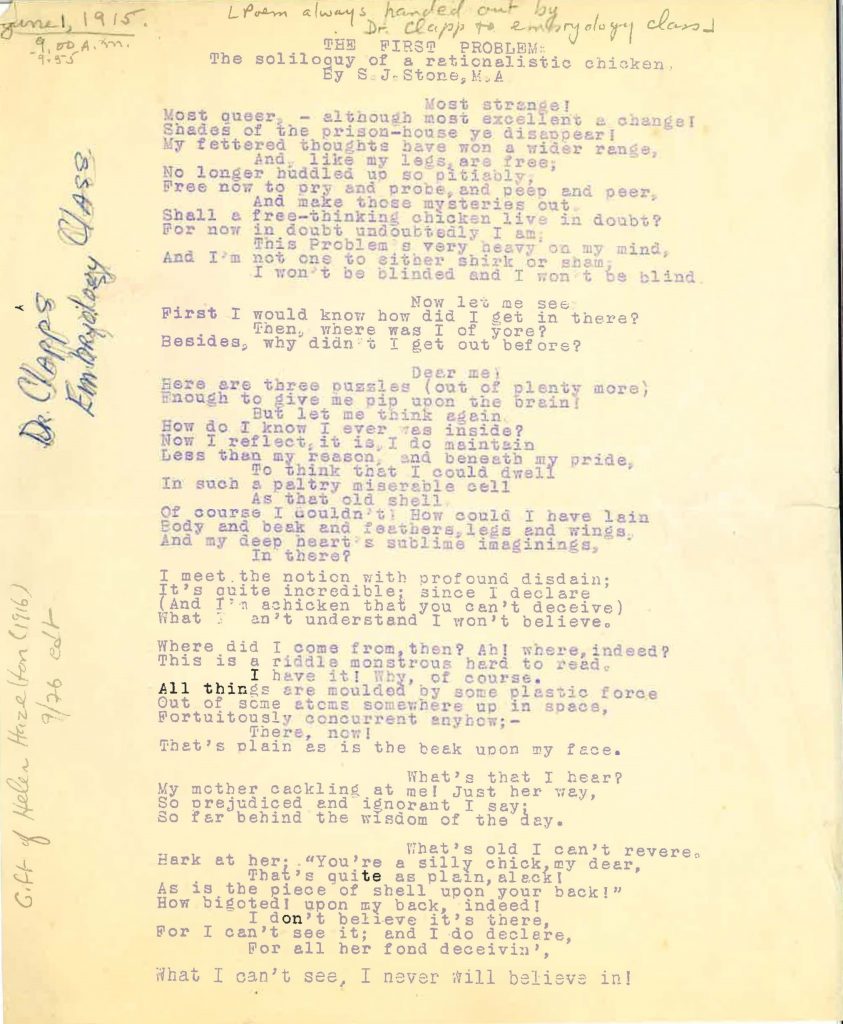

To an early 20th century zoologist like Cornelia Clapp, the origins of both the individual chicken and of chickens as a whole could be found in the contents of its shell. These scientists believed in the now-debunked idea that ontogeny (the development of the individual) repeats phylogeny (the evolution of its species). In this frame, embryology was, in Clapp’s words, “the key to the problems of organic evolution.”

This might explain why on the first day of her embryology classes, Clapp handed out a poem about a “rationalistic chicken” who refused to admit he came from a shell. The chicken’s denial of his origins when he has a bit of shell on his back parallels anti-evolutionists denying humans’ development as a species.

Students often poked fun at Clapp’s laboratory methods, affectionately framing her use of fresh specimens as slightly sadistic. The students who wrote this article drew from experience: if they took zoology, they probably had actually dissected all of these animals themselves.

![Handwritten notes in cursive which read "Zoology-- In use the combination of lecture and recitation [sic.]. No given test book is used-- the pupils are required to learn of the eternal structure of vertebrates by means of an analysis or key to the families-- Jordan's manual of vertebrates is med. The internal anatomy is shown. The dissection of a cat, frog, turtle, or some [sic.] vertebrate. The instruction in invertebrates is given wholly by lectures."](https://commons.mtholyoke.edu/clapp/wp-content/uploads/sites/954/2024/06/Clapp88FINAL-633x1024.jpg)

![Handwritten notes which reads "Protozoa = first animal. Amoeba. [sic.]. Vorticella. Morphology - what is it? A cell = protoplasm, nucleus, cell wall, locomotion organs. Physiology - what does it? I. It eats -- digests -- assimilates. II. It breathes -- oxygen needed. III. It moves -- no organs, fur, the visibility of [sic.], is cause of [sic.]. III. Cyclical development. C. H. O. N. + S.+ P. the proportion of these elements -- the molecular formula has General Biology [sic.]"](https://commons.mtholyoke.edu/clapp/wp-content/uploads/sites/954/2024/06/Clapp71FINAL-1-631x1024.jpg)