Indigenous History at Mount Holyoke College

Indigenizing Campus Menu

This history presented on this page, while non-comprehensive, seeks to provide context for the proposals featured on this site, as well as to act as a resource for those unfamiliar with the history of this land. In order for Mount Holyoke College to re-indigenize its campus, we must first familiarize ourselves with the character of the land and the people that existed here before the college itself. Additionally, we much recognize the institution’s benefit from and contribution to the inherent violence of settler colonialism before we can attempt to heal from it.

Contextualizing the Land

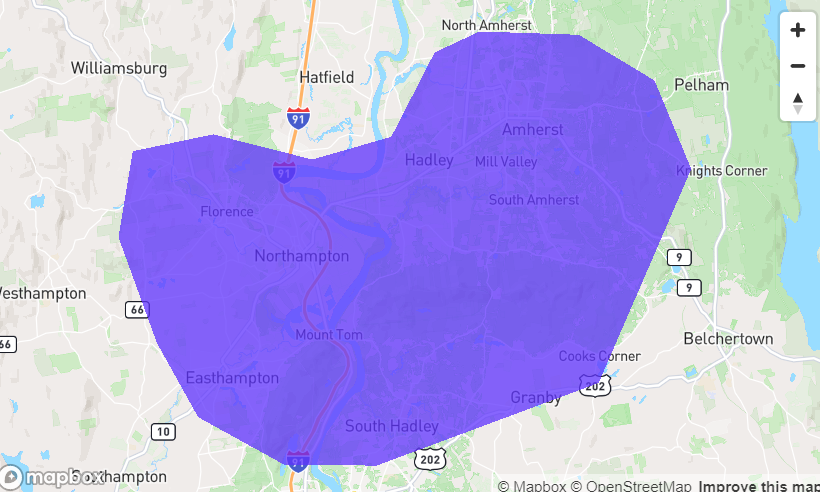

Mount Holyoke College occupies the traditional lands of the Nonotuck people (also referred to as the Norwottuck). ‘Nonotuck’ is a locational term, roughly meaning ‘in the middle of the river’ in Algonkian dialect. This is in reference to the land surrounding the geographical midpoint of the Kwinitekw (Connecticut) River, and the term would in time become synonymous with the Algonkian communities that occupied this region. In addition to South Hadley, Nonotuck land encapsulates Northampton, Amherst, Hatfield and Hadley. Though the region around the Kwinitekw oxbow from which the Nonotuck got their name was geographically distinct from those around it, Nonotuck culture and people maintained extensive contact with other Connecticut River Valley and greater northeastern tribes, both pre and post colonization.

Stories About the Land

Local tribes in the Connecticut River Valley have long told the story of Ktsi Amiska (The Great Beaver) as an origin story of the valley. The mountain often referred to by its settler name, Mount Sugarloaf, was once a giant beaver called Amiskw. On top of the Kwinitekw, Amiskw built an enormous dam in the shape of a wigwam. This dam flooded the valley, and when Amiskw refused to move it, it fell to the Great Transformer to defeat the beaver, using a club fashioned from a tree to break his neck. Where Amiskw fell, his body was turned to stone, creating the mountain–Ktsi Amiskwa–in its place. The water that flooded the valley subsided, and all returned to how it was meant to be.

One rendition of the story, told by Margaret Bruchac, can be listened to here.

Settler Contact and the Myth of Disappearance

In order to re-indigenize the Mount Holyoke College campus, we must first acknowledge the settler practices of violence that it was built on.

In 1671, settler John Pynchon of Hadley made formal purchase of what is now considered South Hadley from a Nonotuck man called Wequogon, his wife, Awonunsk, and their son, Squomp. This land stretched from Mount Holyoke in the north to Stony Brook (which flows through the lakes on the eastern side of our campus) in the south. An additional portion of land was later sold to South Hadley settlers from John Parsons, who had assumed the land as a means of collecting debt from Wequogon and his family. These transactions, however, did demarcate the disappearance of native people in the area. Indigenous people continued fishing, hunting, and even making residence on this land for years after this transaction, their intent and right to do so even being documented in the deeds for these lands.

In 1675, when Wampanoag leader Metacom began a rebellion against English settlement across New England, and it was for him–or rather, his baptized name, ‘Philip’–that King Philip’s War was subsequently named. Although John Pychon attempted to use his trade relations to influence local indigenous people towards neutrality, many joined the rebellion regardless.

In August of 1676, a military group of settlers in Hadley planned to ambush the local Nonotuck people before dawn. This was not inspired by any act of hostility committed against the settlers, but rather a means of scaring and deterring the indigenous group from crossing the English in the future. The Nonotuck, however, had already left early in the morning, following the Kwinitekw to Ktsi Amiskw where Pocumtuck allies waited. When the English pursued them to this point, the battle took up a symbolic significance for the indigenous defenders: Like the great transformer before them, they fought to restore peace and safety to the valley.

After the violence of King Phillip’s war–including the 1676 massacre of nearly 400 indigenous people at Peskeomskut (now Turner Falls), less than 30 miles away from our current-day Campus–many indigenous families sought residence elsewhere. However, they did not disappear or assimilate nearly so quietly or completely as settler accounts may have us imagine.

The turn of the eighteenth century saw a strong shift in New England settler documents and their reference to indigenous people. When John Pynchon died in 1703, for example, with him went a trading relationship that led him to represent indigenous people positively. This gone, narratives of native people as brutish, violent, or lazy became more prolific in writing and recordkeeping. The space that town history books of South Hadley offer to the indigenous people are largely unkind and unflattering. That is, of course, when they acknowledge their presence at all.

The myth of the vanishing native was and is widespread across the Connecticut River Valley and New England at large. After King Philip’s War, the notion that indigenous people had moved elsewhere or died off became a point for settlers to justify the increased occupation and colonization of traditional lands. While there was a significant diaspora of Nonotuck and other local peoples–most of them moving to Vermont, Canada, and the lands around the Hudson river in New York–this was not a miraculous or passive exit. Many found alliance with the other indigenous groups–as many did with the Abenaki to the north–while maintaining their cultural distinction and identity. Many, too, returned to their homelands Connecticut River Valley, if not to visit kin then to resume permanent residence.

Many settler accounts romantically document the deaths of indigenous people who were the ‘last of their kind’. Ironically, of course, many of these individuals were survived by at least one family member. This reflects not only the contrived stories of disappearance, but also the settler conception of indigeneity as something measured by blood or a strict adhesion to traditional ways. The disappearance of indigeneity as something that could biologically be proven, in fact, is a notion that would later be expanded upon within the walls of institutions that now constitute the 5 College Consortium.

Indigenous History and Visibility at Mount Holyoke College

Mary Lyon received the deed for the land on which the original seminary building was built –and on which Mary Lyon Hall now stands–by hand of Emily B. Montague. Emily Montague was the great-granddaughter of settler Peter Montague Jr., who built the first home in South Hadley on that very site in 1720. Peter Montague and his family, like the rest of South Hadley’s early settlers, were encouraged to keep their homes heavily armed in anticipation of pushback from indigenous groups.

Mount Holyoke College is built on land usurped by settlers and maintained by physical violence against and strategic erasure of indigenous people. that equal parts feared and enacted terror upon local indigenous communities. Long after the original colonization of this land, silence was maintained around the history of this land and its original inhabitants–even as local features still bore their names. For years, Lower Lake was called Lake Nonotuck.

In recent years, Mount Holyoke College has engaged in various methods of acknowledging and honoring native communities both locally and at large. Many of these efforts have started at the individual, student-led level. Take, for example, the creation of the Zowie Banteah Cultural Center. This space, dedicated to the visibility and empowerment of Native and American individuals on campus, was founded in 1995 as ‘The Native Spirit’. It was renamed two years later for Zowie Banteah (‘96), who was instrumental in the founding of the center as a student.

Resources

Creation and Deep Time Stories – Historic Deerfield

Five Colleges in the Kwinitekw Valley

In Old South Hadley by Sophie E. Eastman

Mount Holyoke Alumna Embraced Both Parts of Her Cultural Identity.

Native Presence in Nonotuck and Northampton

Profiles of Native People, Historic Northampton

The History of Hadley by Sylvester Judd