Thanks to cast members Lily Hammond, Camille Hodgkins, Chana Freedberg, and Michelle Marinelli Prindle, and MHC Voice Lecturer and 5C Opera Steering Committee member Sherry Panthaki, for taking the time to answer my questions.

If you are going into an opera for the first time, you are probably expecting to hear beautiful arias and duets, and maybe even some dynamic ensemble numbers. You might be less familiar with a style of singing called recitative. Recitative is less musically complex and interesting than the musical numbers, but it is still very important. Oftentimes in opera, recitative is where the most important action takes place, so pay attention!

But you might be wondering, what is recitative? How did it come to be? And why does it do all the work, but get none of the glory? Well, this page is here to answer those questions. First, I will explain what recitative sounds like, when you can expect to hear it in an opera, and provide some examples from The Marriage of Figaro. Then we will look at the development of recitative over time. Finally, we will hear some performers’ perspectives on singing recitative.

What is recitative?

Recitative is essentially musicalized dialogue. It often mimics the patterns of “dramatic speech” (Monson et al 2001). While arias are moments for individual characters to stop the action and express their feelings, recitative is where the action takes place.

When will I hear recitative?

You can expect to hear recitative between musical numbers. Think of it like the dialogue that happens between songs in a Broadway musical. One of the best ways to tell if you are hearing recitative or a sung number is to pay close attention to what each moment sounds like. As we will discuss below, recitative sounds more like speech, while sung numbers sound more musical. There are also differences in how the orchestra is featured.

What does recitative sound like?

Recitative is supposed to sound very speech-like. In the vocal line, that usually means that the range is very narrow and that a lot of text is being delivered in a short amount of time. It also means that there is very little repetition of text. Composers and performers mimic speech in several ways, including by being free with the rhythm, but there are also ways that the orchestra can help make recitative sound more like speech. According to Edward Downes, the harmonic cadences that composers use in recitative suit the alternation between tension and release that exists in speech (Downes 1961). Recitative may not be as musically exciting or intense as sung numbers, but it can be surprisingly musical, depending on the singer’s delivery and the composer’s choices.

There are actually two types of recitative that developed in the 18th century: recitativo semplice (simple), also known as secco (dry) recitative, and recitativo accompagnato. Recitative semplice involves very little accompaniment from the orchestra. Usually, it is just a few instruments playing the bass line, and another couple of instruments adding some realization (chords that work with both the bass and vocal lines).1 Since the accompaniment is so simple, it means that the singer has a lot of rhythmic freedom in how they perform the recitative. Often, there is not even a conductor involved! This freedom allows the singer to make the line very natural and speech-like. Most of the recitatives in The Marriage of Figaro are in this style.

In accompagnato recitative, the accompaniment is played by more instruments, or even the full orchestra. It is more complex, meaning that both the singers and the instrumentalists have to adhere more closely to the notated rhythm. The conductor will probably get involved. Accompagnato is particularly used in “moments of intense dramatic crisis” (Monson et al 2001). Accompagnato might also be used in the recitative that builds up to a musical number.

Examples

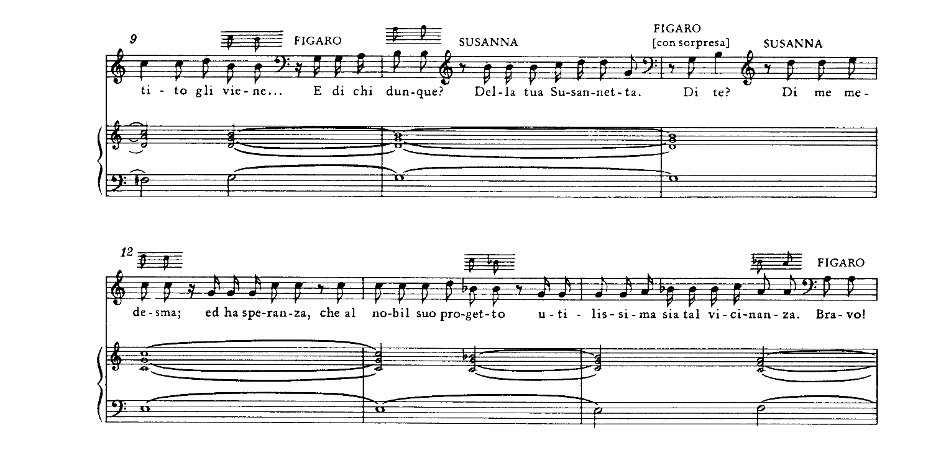

Let’s look at the scene right before Figaro’s aria, “Se vuol ballare.” Susanna has just told Figaro that their employer, Count Almaviva, is planning to seduce her on her and Figaro’s wedding night. Notably, although Susanna and Figaro had a duet (“Se caso madama”) right before this revelation, Mozart set this very important piece of information as recitative. Let’s look at an excerpt from the score:

from Neue Mozart-Ausgabe edition of Le nozze di Figaro

FIGARO: E di chi dunque? SUSANNA: Della tua Susanetta.

FIGARO: Di te?

SUANNA: Di me medesma, ed ha speranza che al nobil suo progetto utilissima sia tal vicinanza.

FIGARO: Who is it, then?

SUSANNA: Your own little Susanna.

FIGARO: You?

SUSANNA: The very same, and he is hoping that to his noble project my being so close will be very helpful.

Text and translation from Vocal Music Instrumentation Index

This is an example of secco recitative. Note that the vocal line has a very narrow range and that the accompaniment is very simple – just tied whole and half notes. If you listen to or watch a recording of this recitative, you might even notice that the orchestra does not sustain those notes for the entire length of the measure, leaving the singers to sing a cappella some of the time.

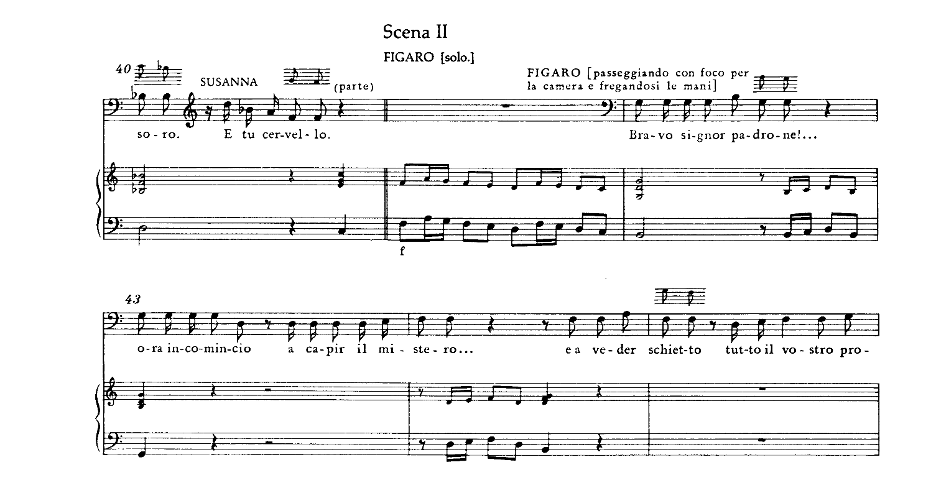

After Susanna leaves to attend to the Countess, the music switches to accompagnato recitative as Figaro continues alone. Here is what the score looks like at this point:

FIGARO: Bravo,signor padrone! Ora incomincio a capir il mistero… e a veder schietto tutto il vostro progetto.

FIGARO: Bravo, my noble lord! Now I begin to understand the mystery and see clearly into the heart of your plans.

Notice that while Figaro’s vocal line is still relatively simple, the orchestra’s part is more rhythmically complex. They are coming in at the end of Figaro’s phrases, as if they are responding to what he is saying. The accompagnato recitative serves to increase the musical and dramatic tension, indicating that a musical number is imminent.

How has recitative developed over time?

One could actually argue that the genre of opera started with recitative! According to Jeffery Langford, opera was developed by Italians in the 1600s who were looking to create a new genre of storytelling by combining music and drama. These Italians looked to the Ancient Greeks for inspiration and theorized that the Greeks chanted their plays in a way that “used pitch to imitate the natural rise and fall of the spoken voice, and used rhythm to capture its dramatic pacing” (Langford 2011, 229-231). So opera started with this form of musical storytelling, and up until 1650, “the moments of most intense passion were generally rendered in recitative, often in long soliloquies,” rather than in arias. Recitative at this time was also more lyrical and melodic than the secco recitative we now know (Monson et al 2001). However, recitative lacks a coherent musical structure and features no repetition, which makes it somewhat difficult to listen to for long periods of time. As Lily Hammond, playing the Countess in the Five College Opera production of Figaro, put it, recitative is simply “not catchy.”2

In the late seventeenth century, the “number opera” developed. In this opera structure, composers interspersed nonmelodic, or secco, recitative with musical numbers. Figaro is a number opera (Langford 2011, 231). In number operas, “recitative came to be the principal vehicle for dialogue and dramatic action in opera, with the arias carrying the more lyric portions, although this traditional understanding of the separation of dramatic function is less rigorous than is sometimes supposed” (Monson et al 2001).

How do performers approach recitative?

To understand how performers go about learning recitative, I turned to the performers in the Five College Opera production of Figaro. All the singers who responded agreed that recitative poses its own unique difficulties when it comes to learning and memorization. Lily Hammond, who plays the Countess, says that this difficulty is caused by the fact that the music is unstructured and features very little repetition. Camille Hodgkins, the cover for the Countess, also noted that recitative can sit in a difficult part of the voice for many singers.3 All of them stated that text is the main feature in recitative, which means that diction and expression are very important for conveying the important plot points that happen in recitative scenes.

Several cast members also emphasized the importance of interacting with and responding to their fellow actors when doing a recitative scene. Michelle Marinelli Prindle, who plays Marcellina, says, “that is what I think is the most important aspect of Italian recitative. We need to sound like these are our own words, and our own intentions, and the dramatic action flows from them. Otherwise, there is no way that the opera can be authentic.”4 That level of acting requires a thorough knowledge of the text and its meaning. Since most operas have so much recitative, and it doesn’t have built-in mnemonic devices like repetition or catchy rhythms, memorization can be a daunting task.

Voice instructor Sherry Panthaki offered her tips on learning recitative. She says that the first step is to understand the text by studying a very accurate translation. After that, the only thing to do is to undertake a process of “slow and careful memorization.”5 Panthaki recommends writing the text out over and over, recording yourself singing it and listening to that recording, and looking at the text first thing in the morning and last thing at night.

Conclusion

So, next time you’re at the opera, make sure to pay attention to recitative. It may not be the most musically exciting part of an opera, but it is certainly very important!

Endnotes

for full citations, see Learn More

- Sherry Panthaki, email correspondence with the author, December 12, 2025. ↩︎

- Lily Hammond, email correspondence with author, November 30, 2025. ↩︎

- Camille Hodgkins, email correspondence with the author, December 2, 2025. ↩︎

- Michelle Marinelli Prindle, email correspondence with the author, December 9, 2025. ↩︎

- Sherry Panthaki, email correspondence with the author, December 12, 2025. ↩︎