Portrait of Beaumarchais (1755) – Wikimedia Commons

In the transition from play to opera, there were several significant changes to the content of The Marriage of Figaro for many different reasons, including time and content. When Da Ponte and Mozart wrote the libretto, it needed to be drastically shortened, but more importantly it needed to be far less controversial. Beaumarchais’ play Le mariage de Figaro had been banned in France by King Louis XVI in 1783, and Emperor Joseph II allowed the publication but banned the performance of the play in Vienna, most likely because of its outright mockery and criticism of aristocracy. The opera was accepted after Da Ponte promised the Emperor he had “omitted and shortened anything that could offend the sensibility and decency of … His Sovereign Majesty” (Carter 1987).

Among these changes were minor changes to dialogue, characterization, and the themes of some monologues in their adaptation to arias. There were several major, noticeable changes as well. Beaumarchais’ court scenes in Act III, in which the characters are actively navigating the Count’s judicial power, are omitted. And Figaro’s monologue in Act 5, where he directly condemns the aristocracy, is turned into his aria “Aprite un po,” a sexist piece about women’s supposed fickleness.

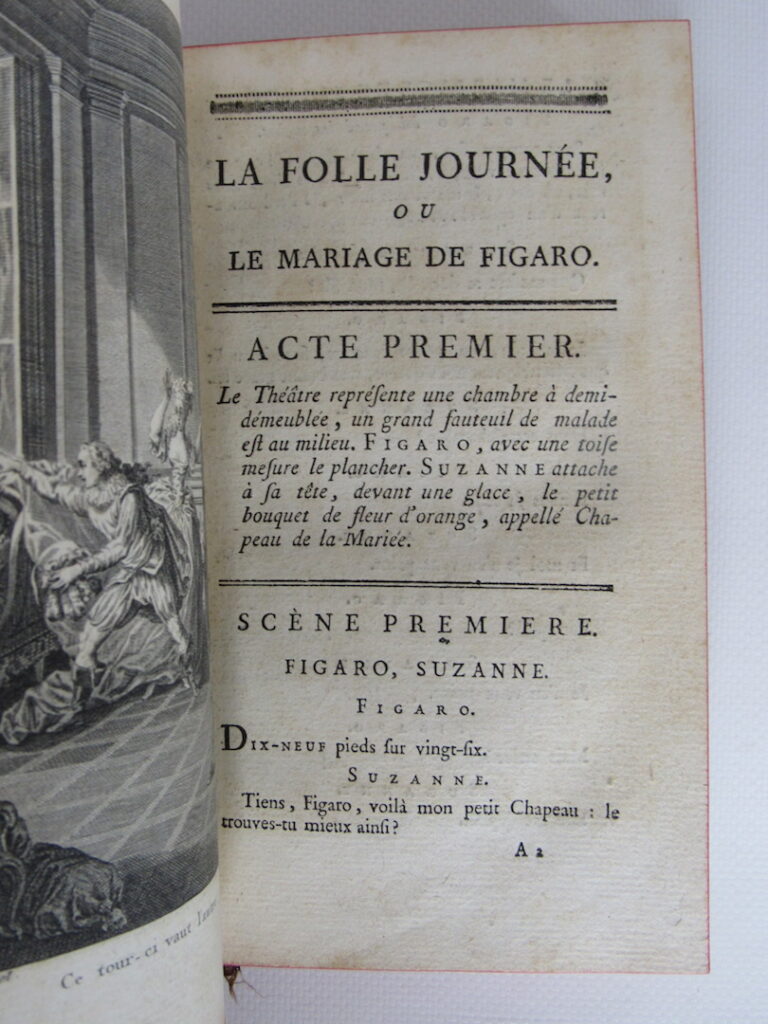

First edition of Beaumarchais’s Le Mariage de Figaro, page 1 – Librarie le Feu Follet

The first omission of an anti-aristocracy theme occurs in Act 1, Scene 1. In both the play and the libretto, the first scene introduces the main characters, setting, and atmosphere. It is a dialogue between Figaro and Susanna, arguably the two most important characters in the story, that also introduces the initial power struggle between them as servants and their “lords,” the Count and Countess.

Both the play and libretto include a comical back and forth between Figaro and Susanna where they are arguing about the new location of their room:

Engraving of Act 1, Scene 1 – Susanna admiring her hat in the mirror, and Figaro measuring the room. From Orphea Taschenbuch für 1827 (MDZ)

Beaumarchais play (translated):

FIGARO: If her Ladyship doesn’t feel well in the night, she’ll ring from that side and, tipperty-flip, you’re there in two ticks. If his Lordship wants something, all he has to do is ring on this side and, hoppity-skip, I’m there in two shakes.

SUZANNE: Exactly! But when he rings in the morning and sends you off on some long wild-goose chase, tipperty-flip, he’ll be here in two ticks, and then, hoppity-skip, in two shakes….

Da Ponte libretto (translated):

FIGARO: If Madame should call you in the evening – ding, ding – you can be there in two steps. If the occasion arises that the master calls me – don, don – I can be at his service in three jumps.

SUSANNA: (ironically) If in the morning the dear Count commands you three miles away, the devil appears at my door, and then in three jumps…

In both versions, we immediately get a sense of the fun banter that Susanna and Figaro have, as well as the lighthearted atmosphere of the whole story. It also introduces the recurring idea that Susanna is more intelligent than Figaro, and that he cannot see through the plans of the Count just as he cannot see through the Countess’ final plan to expose the Count at the end of the opera.

Another small change may not be noticeable at first, but it alters the entire political power dynamic. During the first scene in the Beaumarchais play, Suzanne, the counterpart of Susanna, says this:

SUZANNE: He means to use the money to persuade me to give him a few moments in private for exercising the old droit de seigneur he thinks he’s entitled to…You know what a disgusting business that was.

This quote references directly the droit du seigneur, the feudal right of a lord to spend the first night with the bride of his serf in order to “deflower” her. It may have not been an actual legal right, but was still practiced anyway as an informal form of tyranny (Andrews 2001). This supposed right has been referenced in various different theatrical settings, but never with a connotation of opposition like that of Figaro. In the quote above, Suzanne explicitly calls this right “disgusting,” a direct anti-aristocratic opinion leading to the political controversies held about this play. The opera includes the Count’s infidelity, but only mentions droit du seigneur through allusions and is never explicitly shamed.

Engraving from Act 3 – The Count attempts to seduce Suzanna. From Orphea Taschenbuch für 1827 (MDZ)

Although the opera kept the major storyline and important themes of political struggle, there were a lot of important political topics lost in the transfer from the play. In adapting Figaro’s Act V monologue into the “Aprite un po” aria and dropping the shame of droit du seigneur, Da Ponte takes out all explicit criticism of the aristocracy. The main apparent power struggle remains an integral part of the storyline, including the existence of the Count’s wish to spend Susanna’s wedding night with her. Making the libretto more aligned with Emperor Joseph II’s wishes did not completely get rid of anti-aristocratic themes, but it did make it harder to pick up on those themes. Did the Emperor just not read into the libretto enough?