In The Marriage of Figaro (Le Nozze di Figaro), an opera written by an Austrian composer, sung in Italian, and based on a French play, the original place setting of Spain can often get lost in translation. Though the opera is set in Seville, it is important to distinguish between the actual locale and the perceived interpretation of Spain seen in artistic choices made in the opera’s text, music, and staged productions. This article will explore Spanish references that appear throughout the opera and how certain productions highlight Sevillian architecture in set design, thus centering the opera’s Spanish setting.

An Opera Set in Seville, Spain

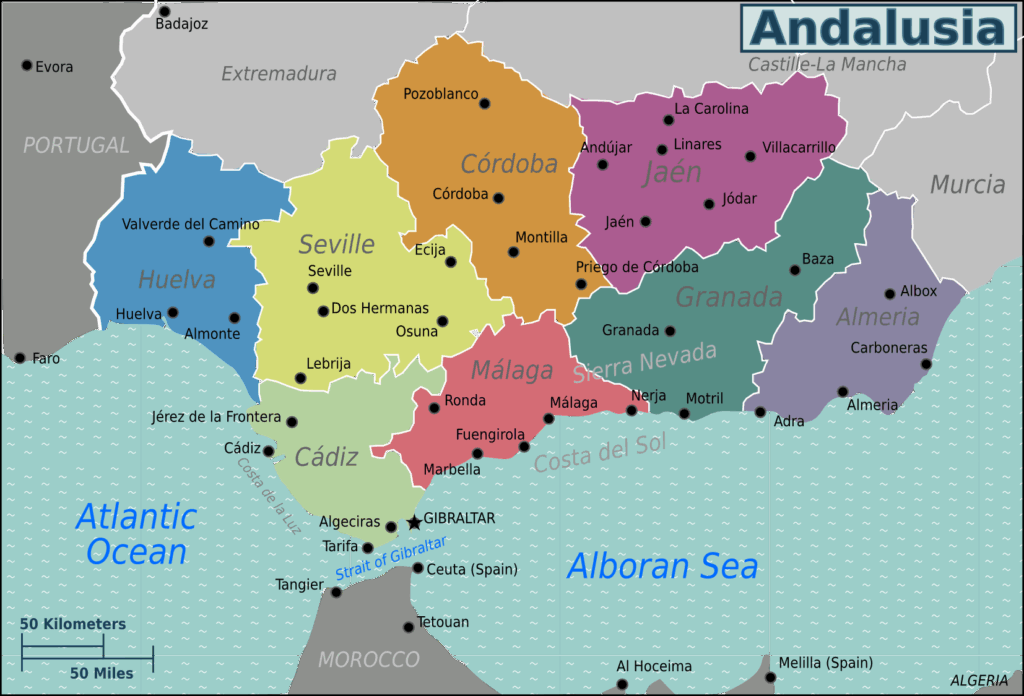

As prescribed by the 1784 play Le mariage de Figaro, by Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais, the opera is set in “the chateau of Aguas-Frescas, three leagues from Seville.”1 Seville, a prominent city in the south of Spain, is the capital city of the autonomous region of Andalusia and is situated on the left bank of the Guadalquivir River.2 Andalusia has a history of connections with Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, still seen today in architecture in Seville, Granada, and Cordoba. As an inland port, Seville is one of the largest centers for trade and is connected with countries bordering the Mediterranean Sea and countries in North Africa.

Highlighted city of Seville on overall map of Spain – Britannica.com

Regional map of Andalusia – Wikimedia Commons

Photo of the Seville cityscape – Business Insider

Seville became a popular destination for Europeans travelling in the 19th century after the city was highly featured by name or in setting in many operas and musical compositions, including Mozart’s Le Nozze di Figaro and Don Giovanni (1787), Ludwig van Beethoven’s Fidelio (1805), Gioachino Rossini’s The Barber of Seville (1816), and Georges Bizet’s Carmen (1875). Though Seville was never actually visited by any of these composers, the perceived notion of what the city is thought to be has been shaped by the references made in artistic and musical works, sometimes based on cultural assumptions and sometimes based on reality.3

Spanish Allusions by Beaumarchais and Mozart

Before writing Le Barbier de Séville and its sequel, Le Mariage de Figaro, in 1775 and 1784, respectively, Beaumarchais spent eleven months in Madrid in 1764 and 1765.4 Though he never visited Seville, Beaumarchais encountered dance forms, theatrical performances, and Spanish cultural customs in Madrid that inspired his selection of Seville as the place setting for his two most important works.

The Act 3 Fandango

The fandango, performed by one couple consistently snapping their fingers along to their “gyrating hips and suggestive movements,” is most prominently featured in the wedding scene in the Act 3 finale of both the play and the opera.5 This explicit Spanish reference creates a veil of mystery, signaled by its minor key and percussive triple meter rhythms, under which Susanna slips the Count the note to meet her in the garden later on.

Pierre Chasselat, Fandango Dancers (1814) – Wikimedia Commons – This painting depicts 19th-century Castilian folk dancers dancing the fandango in two pairs of couples, accompanied by a guitarist.

The exact choreography differs with each production, due to score markings made by Mozart in the original score of Le Nozze of “figuranti ballano” and “Figaro balla” which call for professionally trained dancers and Figaro to dance, yet there are no indications of how to actually perform it nor how it is important to the plot.6 The fandango within Figaro primarily functions as a touch of “local color,” which refers to the place setting of a work as marked by its “costumes, landscapes, or peculiarities.”7

The lack of technical specification has caused an overall dearth of fandango accuracy in productions today, where directors often employ the singers in the ensemble to perform the dance instead of hiring professional fandango dancers (as called for by Mozart), thus causing the choreography to vary in each performance.8 Though not identical across most productions, the fandango choreography in Figaro usually features common elements of snapping, raised arms, rhythmic foot stomping, and bodily separation between the two dance partners. In the following two productions, the choreography and marking for the fandango scene differ between stomping, clapping, and audible cheers from the ensemble.

Grand Theater of Geneva, 2017

Royal College of Music, 2025

Through writings of Beaumarchais and other eighteenth-century travelers to Spain, the fandango has been characterized by its sexual connotations and “lascivious nature,” where gestures of sexual activity are signaled without any physical contact by either partner of the dance, producing a degree of sexual tension.9 Upon seeing first-hand how the fandango was performed in Spain, Beaumarchais remarked,

“Normal dancing is absolutely unknown here, by which I mean the figured dance…The most popular here is something called the fandango, whose music has an extreme vivacity and whose entire amusement consists in making lascivious paces or movements.”10

Beaumarchais refers to the absence of “figured dance” which alludes to French courtly dances, including the minuet and the gavotte, that dominate the rest of the music of Figaro. The fandango, in sharp contrast with the squared-off, courtly dances, is significant in its open-ended and spun-out musical phrases, signaling an important moment in the opera that sets up the intrigue of the fourth act, since the opera does not end with the wedding .11 The music itself is in line with how the fandango would have sounded in the 18th century, as mirrored in other compositions of the fandango by Domenico Scarlatti and Felix Maximo López.12

1. An example of how the early fandango would have been danced can be seen here, by historical dancer Peggy Murray. This video is from the NYS Baroque and Pegasus Early Music ensemble in 2019.

2. This video of a fandango in the ballet Don Juan (Christoph Willibald Gluck, 1761) is very similar to the musical writing of Mozart’s Act 3 fandango in Figaro. Both fandangos feature triple meter with similar phrase structures, staccato in the strings, and minor keys. This performance took place in 2024 at the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague, and was choreographed by Helena Kazárová.

3. Kazárová’s choreography is similar to the choreography by Kate Flatt for the fandango in Garsington Opera’s 2017 production of Figaro, as can be seen here.

Seville by Name

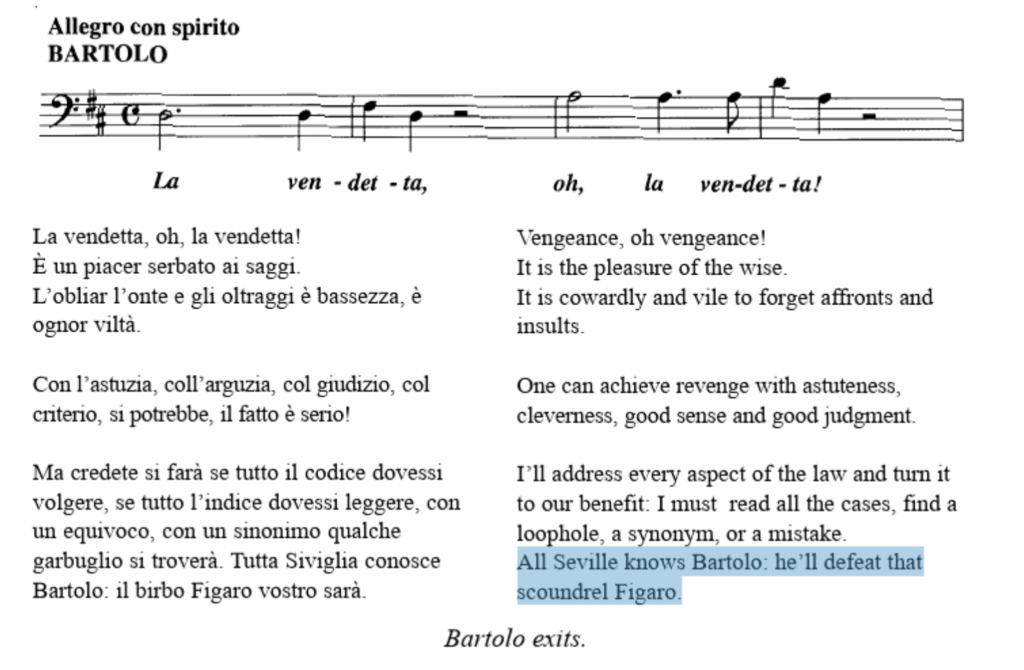

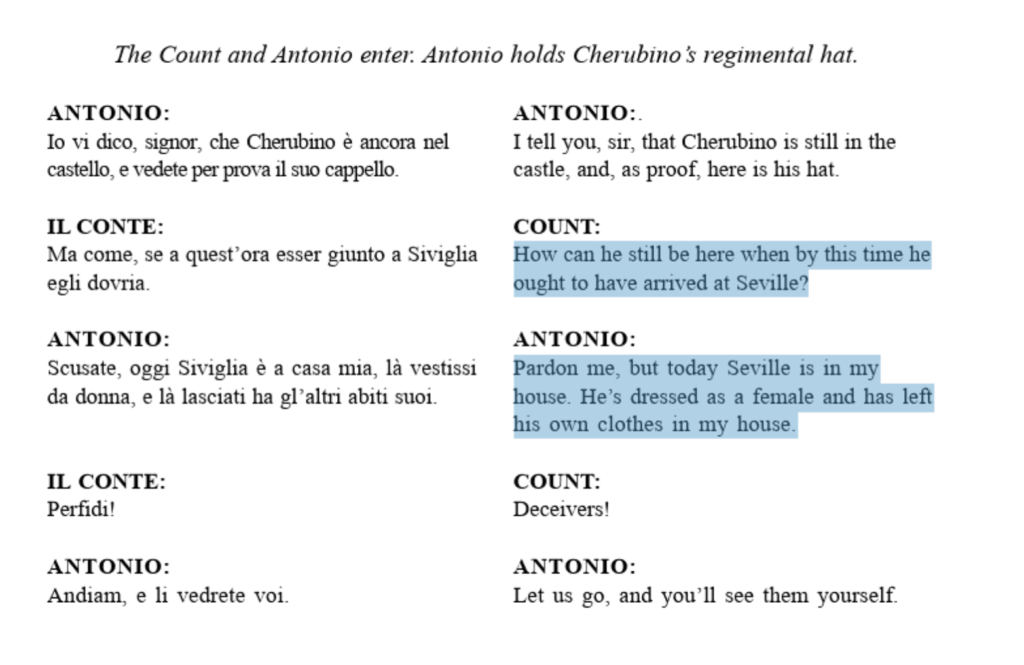

Other than the fandango, only minimal references to Seville occur in Figaro’s libretto, mostly in reference to the guitar and mentions of the city’s name itself in Bartolo’s aria “La Vendetta” and in the banishment of Cherubino to the Count’s regiment in Seville (all libretto excerpts from Fisher 2001).

The Guitar

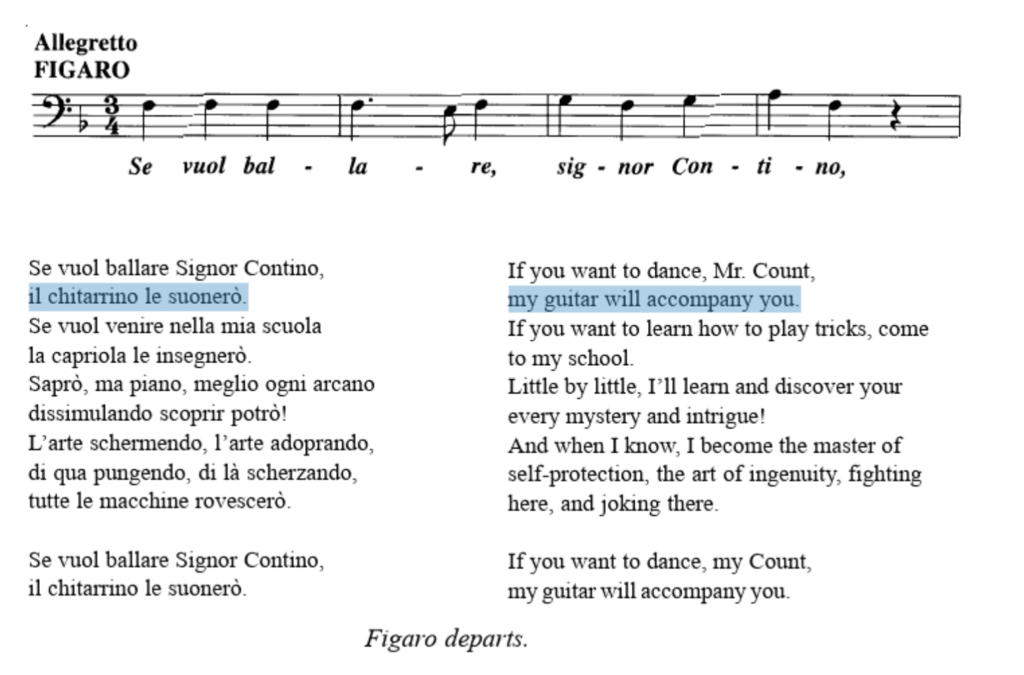

Though the guitar’s origins are unclear, and the bulk of its original repertoire developed in Italy, Spanish artisans still had a major influence on the development of the instrument’s form itself, contributing to the guitar’s associations with Spain.13 Throughout the eighteenth century, the guitar in Spain was used primarily for facilitating national dance music.14

1. Figaro mirrors this practice in the first reference to the guitar occurring in Figaro’s cavatina “Se vuol ballare,” where he sings about making the Count dance the capriole, accompanied by his guitar. Pizzicato in the strings mimic the sound of a plucking guitar as Figaro sings.

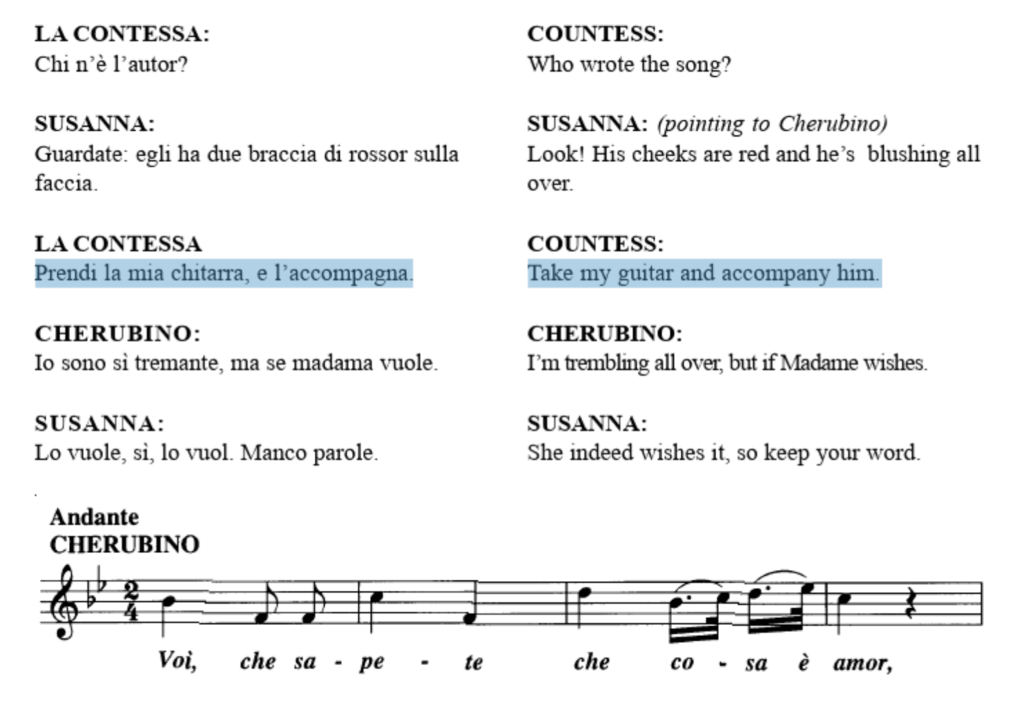

2. Then, in Act 2, right before “Voi che sapete,” the Countess tells Susanna to “take my guitar and accompany him.” Susanna proceeds to play the guitar, as mimicked by pizzicato in the strings, and Cherubino begins his love ballad.

The stage direction written in Le Mariage de Figaro by Beaumarchais directs the staging of this scene in the opera, as indicated in the play:

“The Countess, who is seated, holds the paper and follows the words. Positioned behind her chair, Suzanne plays the introduction, reading the music over the Countess’s shoulder. Cherubin stands facing them, head lowered. This composition is an exact replica of the print after Vanloo entitled: The Spanish Conversation.” 15

Though seen today as minute, the references to the guitar would have been an obvious reference to Spain, based on the public’s knowledge of the painting The Spanish Conversation.

Carle van Loo, Spanish Concert (Spanish Conversation) (1754) – Wikimedia Commons

Regionally Accurate Set Design

In certain modern productions of Le Nozze di Figaro, set designers have incorporated Islamic architectural references found in Seville buildings and more broadly in the Andalusia region, including the Cathédrale de Seville, the Alcazar in Seville, and the Alhambra in Granada (building pictures seen in comparison with set designs below). The surviving Islamic architecture in Seville originates from the 12th century when Seville was the capital city of the Almohad Islamic Caliphate, led by Berber groups in Morocco.16 The Almohads were strict in religion and stylistically preferred architecture focusing on ornament, geometric design, and decorative restraint.17 Overlapping geometric patterns were utilized to encourage the viewer to focus on spiritual contemplation and meditative thought. By having regionally accurate sets and setting the production itself in Seville, the musical allusions to Spain make a lot more sense, and audience members are able to understand the cultural specificity of Seville far more.

1. The Metropolitan Opera 2014-Present Production

In the Metropolitan Opera’s 2014-present production of Figaro set in 1930s Seville, set designer Rob Howell was inspired by the Almohad architecture on the Puerta del Perdon, or door of forgiveness, at the Cathédrale de Seville, a site that represents the various religious influences of the region. Following the Christian Castilian conquest, Seville became the capital of the kingdom of Castile in 1248, and the Castilian rulers built a cathedral over the Almohad mosque, yet the bronze doors were preserved.18 The monochromatic, interweaving, geometric forms on the intricate cage-like set of the Metropolitan Opera recall the interlocking lozenges and confined arabesque ornament of the bronze Sevillian doors. The geometric, grid-like door with clear delineations seen behind Cherubino is reminiscent of the contained decorative spaces on the Castilian-appropriated Almohad minaret that is now used for the bell tower of the Seville Cathédrale, known as La Giralda today.

Hear director Richard Eyre speak about the set design inspiration and overall production here.

Top image: Photograph of Metropolitan Opera set, photographed by Ken Howard – Guild Hall

Bottom left-hand image: Photograph of the door knocker of the Puerta del Perdon – Wikimedia Commons Bottom center image: Photograph of Isabel Leonard as Cherubino and Marlis Petersen as Susanna, photographed by Ken Howard – WQXR

Bottom right-hand image: Photograph of La Giralda bell tower – Wikimedia Commons

2. The Nevill Holt Opera 2018 Production

In the 2018 Nevill Holt Opera production in the Leicestershire countryside, set in eighteenth-century Spain, set designer Simon Kenny pays homage to the Seville Alcazar, produced in the Almohad style. The arches made up of many smaller arches within one larger arch, supported by two small columns on each side, are reminiscent of polylobed arches that are commonly found in Islamic architecture. The two-story, closed-in courtyard is replicated in the white, simplified set, and the low relief sebka ornament, or interwoven lattice, is mimicked by the crossing diamond motifs between each arch.

Top image: Photograph of the 2018 Nevill Holt Opera set, taken by photographer Robert Workman, courtesy of Simon Kenny

Bottom image: Photograph of the Patio de las Doncellas – Headout Blog

3. The China National Center for the Performing Arts 2013-present Production

In Beijing, at the China National Center for the Performing Arts, Seville-born director José Luis-Castro enriches the opera by adding details specific to Renaissance Seville to the set and dramaturgical direction of the opera, using his lived experience as a Seville resident, though not highlighting the Islamic side of the architecture.

Set photograph, 2013 China National Center for the Performing Arts production – TheatreBeijing.com

4. The Glyndebourne Opera Festival 2012 Production

Christopher Oram’s design for the 2012 Glyndebourne Opera Festival production, set in 1960s Spain, is one of the most clear examples of Islamic architecture-inspired set design . The stage rotates between the different sections of the set, as explained in this video by director Michael Grandage.

Screenshots of the 2012 Glyndebourne Opera Festival set models from the Glyndebourne set tour Youtube video

The walls of the set reference the colorful, geometric tiles of the Alhambra in Granada, and the rounded chairs reference the horseshoe shaped arches that were typical of the region.

Top image: Photograph of Soraya Mafi as Susanna and Nardus Williams as Countess Almaviva in the 2022 Glyndebourne tour production, using the same set – Glyndebourne

Bottom image: Photograph of tiles at the Alhambra in Granda, Spain – Alhambra de Granada

Top image: Photograph of Gyula Orendt as the Count, Rosa Feola as Susanna and Natalia Kawalek as Cherubino. By Robbie Jack. – Guardian

Bottom image: Photograph of tiles at the Alhambra in Granda, Spain – Alhambra de Granada

One of the sides of the rotating set is almost an exact replica of the Patio del Yeso at the Alcazar in Seville. Similar to the real Almohad arcade with a central arch flanked by smaller triple arches, the spaces between the pointed poly-lobed arches are filled with sebka patterns, formed from two different positive and negative patterns: overlapping diamonds (positive) and a shape resembling the fleur de lys or khamsa (Hand of Fatima) which is formed by the negative spaces of the stone cutouts. 19

Tip: Use the slider bar in the middle to scroll between each photo and compare their striking similarities!

Left-hand image: Photograph of the Patio del Yeso at the Alcazar de Sevilla – Wikimedia Commons

Right-hand image: Screenshot of the set model from the Glyndebourne set tour Youtube video

Conclusion

The presence of Spain in The Marriage of Figaro is represented through references in the opera’s libretto to the city’s name and references to the guitar. The inclusion of the fandango scene adds a sense of local color, and regionally accurate set designs enhance the understanding of Seville as a setting. It can be argued though, that using the semi-accurately choreographed fandango and the semi-accurate symbol of the guitar to characterize Spain indicates the cultural flattening of Spanish culture by European artists. Using real-life references to architectural elements specific to Seville and Andalusia aids the audience’s comprehension of Seville as a real place, rather than an imagined foreign land, as well as the musical allusions to Spain in music and in text.

Endnotes

for full citations, see Learn More

- Beaumarchais, trans. Coward 2003, The Marriage of Figaro, 83. ↩︎

- Fernández-Armesto, Felipe, et. al. 2003, “Seville.” ↩︎

- Thomas 2006, Beaumarchais in Seville: An Intermezzo, ix.

↩︎ - Thomas 2006, Beaumarchais in Seville, ix. ↩︎

- Link 2008a, “The Fandango Scene in Mozart’s Le Nozze Di Figaro”: 81-82. ↩︎

- Link 2008b, “Performing the Fandango in Mozart’s ‘Le Nozze di Figaro.”

↩︎ - Hart ed. 1986, “Local Color.”

↩︎ - Link 2008b, “Performing the Fandango,” 1. ↩︎

- Thomas 2006, Beaumarchais in Seville, 120. ↩︎

- Thomas 2006, Beaumarchais in Seville, 120-121. ↩︎

- Allanbrook 1983, Rhythmic Gesture in Mozart, 154.

↩︎ - Felix Maximo López, “Variaciones del fandango Espanol” (Naxos, track 8)

Domenico Scarlatti, “Fandango portugues” (Naxos, track 14)

↩︎ - Heck et al 2001, “Guitar.”

↩︎ - Wheeldon 2017, “The Spanish Guitar.”

↩︎ - Beaumarchais, trans. Coward 2003, The Marriage of Figaro, 115. ↩︎

- Fernández-Armesto et al. 2001, “Seville.” ↩︎

- Dodds ed. 1992, al-Andalus: The art of Islamic Spain, xxi.

↩︎ - Dodds et al, 2008, The Arts of Intimacy: Christians, Jews, and Muslims in the Making of Castilian Culture, 192.

↩︎ - Pérez 1992, “The Almoravids and the Almohads: An Introduction,” 78. ↩︎