https://collection.theatermuseum.at/en/objects/die-hochzeit-des-figaro-995823-1

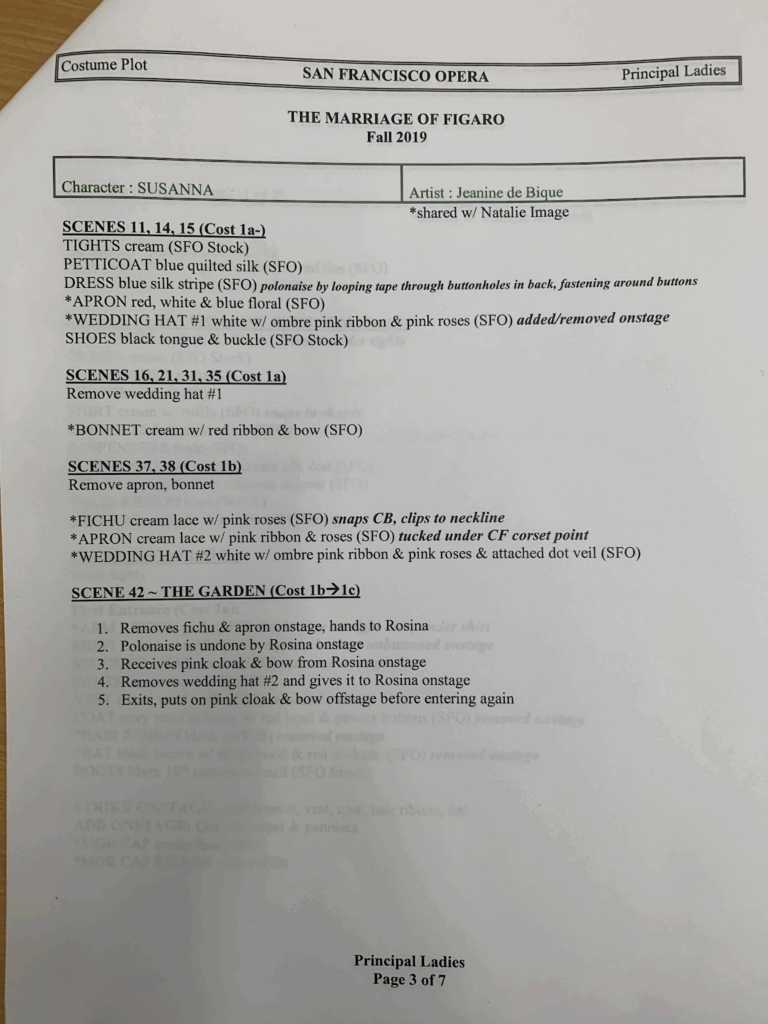

There is no uniform “Susanna look”, but certain musical cues require certain elements of her dress.1 The first notable element of her design is the bonnet, which can be seen in Figure 1. In an interview with the costume designer for the San Francisco Opera, Constance Hoffman discusses the complexity of Susanna’s headpieces.

“Susanna has a wedding bonnet that needs to be quickly attached and removed […] in Act I and Act IV. If she were wearing the bonnet for real use, it would be affixed with several hat pins. But there is no chance to do that in the time she has on stage, so our Susanna […] has magnets built into her wig, with corresponding magnets on the hats! She also has two hats – one for Act I when it needs to be thrown around, and one for Act IV that has the lace veil for the night-time disguise.”

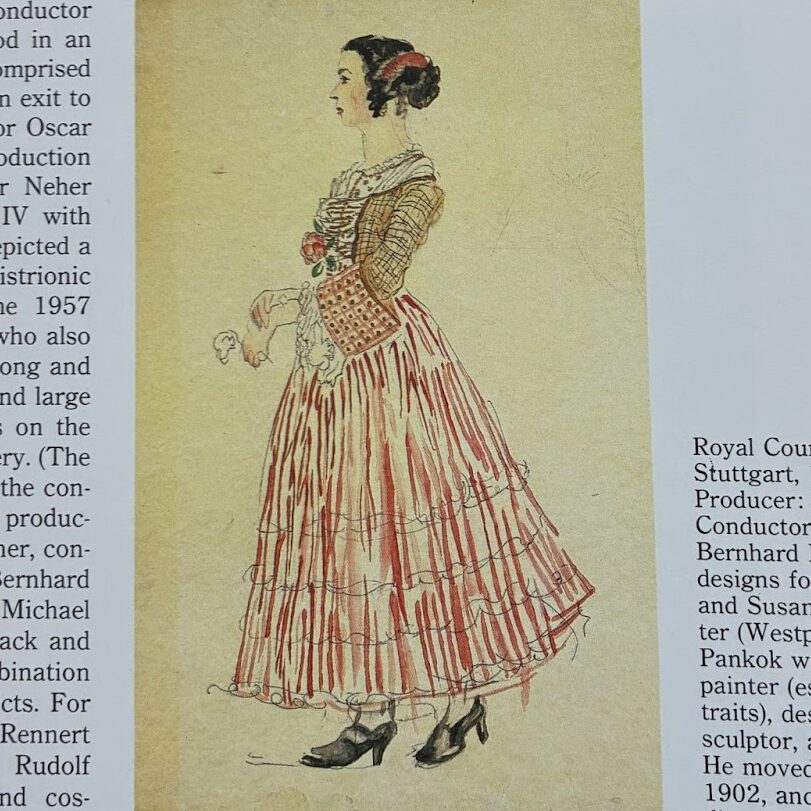

Another interesting element required for Susanna’s costume design is the pockets. The Marriage of Figaro involves many letters to be passed around and, therefore, pockets to hold them. However, women in the 18th century did not typically have pockets; instead, they had something like a slit in their dress that allowed them to reach pouches (sfopera). For a costume designer, this is where the line between historical accuracy and practical effects must be artistically drawn. Functionality may not have been important for fashion back then, but for theatrics, it certainly is.

Modern-day production design

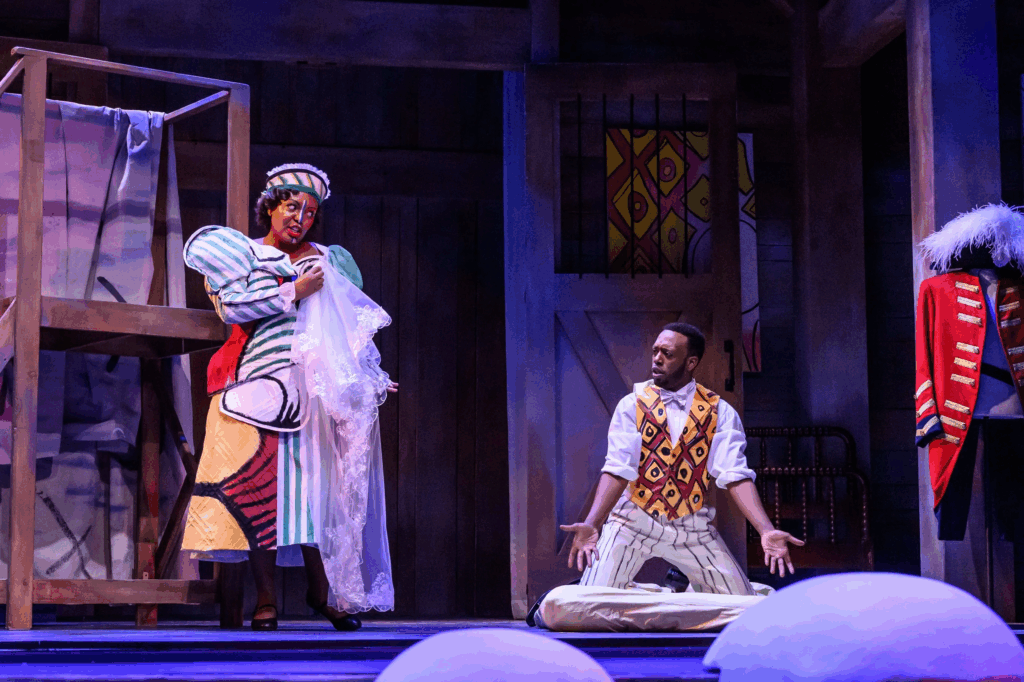

The work of Picasso has a significant influence on Director E. Loren Meeker’s production of The Marriage of Figaro, serving as a feminist statement. The development and “chaos” of these costumes occur over the duration of the opera. In the opening scene, Figaro symbolically represents a painter at work. Susanna and the Countess’s costumes develop by gaining more “clarity” throughout the opera, as they find themselves. Picasso was known to be an objectifier of women, and through the women losing their “picasso quality”, they escape the control of men. This is a statement that would not have been read through the plot had the production sticked to “historically accurate” time-period costumes. The men of the opera counter this, as they represent the chaos that Picasso painted.

Costume design offers infinite creativity. The historically accurate parameters of The Marriage of Figaro’s production are not strict enough to fully guide what the characters wear, so taking as much creative liberty as possible is ideal. Classical operas are not going anywhere, but society is.

Picasso’s work only manifests through the costumes in this production, which is incredibly genius. It shows that costumes are the perfect opportunity for creative design, critical thinking, and political statements.

- “It is striking that there were no uniform ostumes, and that the sets for The Marriage of Figaro were also used in other works. For example, Brioschi’s set design for Act II, the Countess’s boudoir, at the Vienna Court Opera, was also used in Le Postillon de Lonjumeau by Adolphe Adam, while his “French garden,” first seen at the Vienna Court Opera in 1866, also appeared in Lucia Lammermoor by Gaetano Donizetti.” Mozart’s Operas, page 140-141. ↩︎