Cherubino: a young, frivolous page working for Count Almaviva, who desires all women and in particular, Countess Almaviva, due to his boyish adolescence and his raging pubescent hormones. But with a slight twist…he is actually a woman!

The male-presenting character role of Cherubino is traditionally played by a woman, or a mezzo-soprano-voiced individual, as described by playwright Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais in his description of the character “Cherubin” in his 1784 Le Mariage de Figaro, the French play that inspired Mozart’s 1786 opera, The Marriage of Figaro:

“This part [Cherubin] can only be played, as it was, by a pretty young woman. The stage currently boasts no young male actor mature enough to grasp all its subtleties.” Beaumarchais continues, saying “he has reached puberty but knows nothing, not even what he wants, and is completely vulnerable to every passing event.”1

In Le nozze di Figaro, Cherubino (the Mozart equivalent of Beaumarchais’s Cherubin) is one of the most iconic examples of trouser roles in opera.

Engraving of Act 2, Scene 3 – Susanna dressing Cherubino as a girl, and the Countess gazing lovingly. From Orphea Taschenbuch für 1827 (MDZ)

History of the Trouser Role

John Collet, Hand-colored mezzotint of an actress, “Miss Brazen,” getting ready for a trouser role, 1779 – Wikimedia Commons

Trouser roles, also called breeches roles, date back to the second half of the eighteenth century, when female identified singers were cast as young male or beardless characters in order to achieve the correct voice color of a young boy.2 This phenomenon rose to prominence in the 1740s following the decline of the number of castrati singers (male singers who were castrated before reaching puberty to retain their high-pitched voice).3 As a solution, mezzo-soprano women were cast as young boys in their place, since they could best approximate the tone color and bodily figure of a pubescent boy. Trouser roles allowed women to sing in operas and increased the opportunity for women to act on stage.4 Early trouser roles could even be considered as some of the first forms of drag kings!

The role of Cherubino differs from other trouser roles of the time, as Mozart chose to cast a woman to sing Cherubino’s role, following Beaumarchais’ wishes. In other words, he was not forced to find a substitute for a male castrato to fill Cherubino’s role, as castrati were in demand more often in opera seria and less frequently in comic operas, or opere buffe, like Le Nozze di Figaro.5 For Beaumarchais and Mozart, casting a woman to play Cherubino was done explicitly to create sexual ambiguity and add to the confusion and layers of “sexual anarchy.”6 As author Margaret Reynold writes, “Cherubino is about mistaken identity, liminality, and tease.”7

Cherubino’s Queer-Coded Arias

Cherubino is known as an erotically charged character going through the many confusing emotions of puberty, as heard in his two arias: “Non so più” and “Voi che sapete,” both which express his rapidly changing emotions and erotic longings for all women in the castle, and above all, the Countess. In Act 2, Number 11, Cherubino confesses his love to the Countess when he sings her his famous arietta, “Voi che sapete”: a lilting love ballad written by Cherubino himself, expressing his innermost desires for her, both emotional and physical. The arietta’s simple musical form and sparse orchestration, with an undercurrent of pizzicato in the strings mimicking Susanna’s “guitar” accompaniment, symbolize the quickening heart flutters of an intimate, vulnerable moment where Cherubino exposes his true feelings to the Countess. The audience then watches with bated breath as the Countess is wooed by his love song and begins to swoon back, while Susanna teases them both, contributing to the queer reading of Cherubino’s character and stage presence.

Gaëlle Arquez as Cherubino and Susanna Phillips as Countess Almaviva in 2018 Metropolitan Opera production – photo by Marty Sohl

In “Venite inginocchiatevi,” the aria following “Voi che sapete,” Susanna dresses Cherubino up as a girl to send him to the garden that night to confuse the Count further. This creates an interesting effect on the Countess, who swoons even further as Cherubino is progressively dressed more and more like a girl. If there was any confusion over Cherubino’s gender before, it is certainly elevated by Susanna dressing up a male character, played by a female singer, as a girl.

The perceived queer-coded, cross-dressing, and gender-bending complexities of a traditionally female singer playing a male character who chases after female characters would not have been lost on the audience. Many modern productions of Le Nozze di Figaro play up the sexual tension in “Voi che sapete” by emphasizing Cherubino’s nervousness and naiveté that quickly grow into a swaggering bravado. In the following two productions of Le Nozze di Figaro, the gender confusion and sexual tension is evident.

Théâtre du Châtelet, Paris 1993

(“Voi che sapete”” starts at 53:37)

In this production, Cherubino begins singing his aria in a very nervous, self-conscious manner, gasping for breath and fidgeting with his collar. The tempo is noticeably increased, emphasizing Cherubino’s nervousness for dramatic effect. As he sings on, he becomes more comfortable and gains a sense of confidence, turning and making direct eye contact with the Countess, which makes her even more enamored.

Royal College of Music, London 2018

(“Voi che sapete” starts at 56:07)

In this production, Cherubino lengthens his musical phrases to show his erotic longing. The audience watches with excitement as the Countess is visibly moved by Cherubino’s confidence and tries to restrain herself from returning his affections. She becomes more flirtatious with Cherubino as he is dressed more and more like a girl in “Venite inginocchiatevi” and in the recitative following it (1:00:35).

Visual Representations of Cherubino in Art

Throughout The Marriage of Figaro’s storied history, many artists have created artworks accompanying both Mozart’s opera and Beaumarchais’ play to provide a visual representation and to expand audience interpretations and exposure to the story. The depictions of Cherubino vary, some leaning into the queer coding of his character.

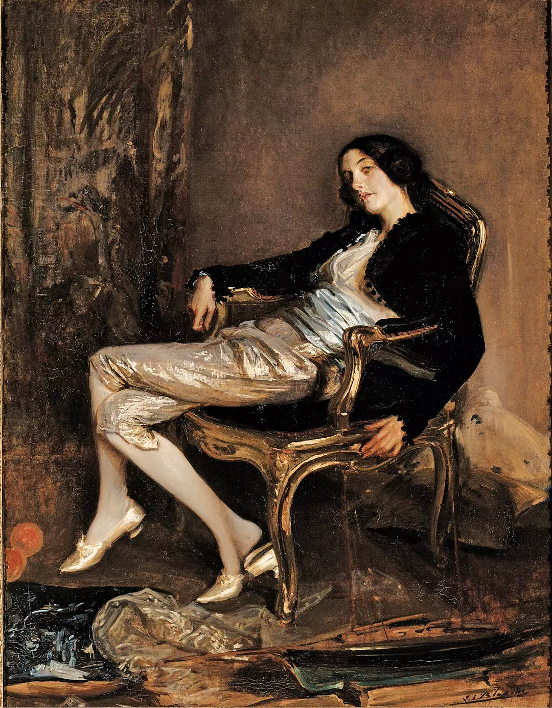

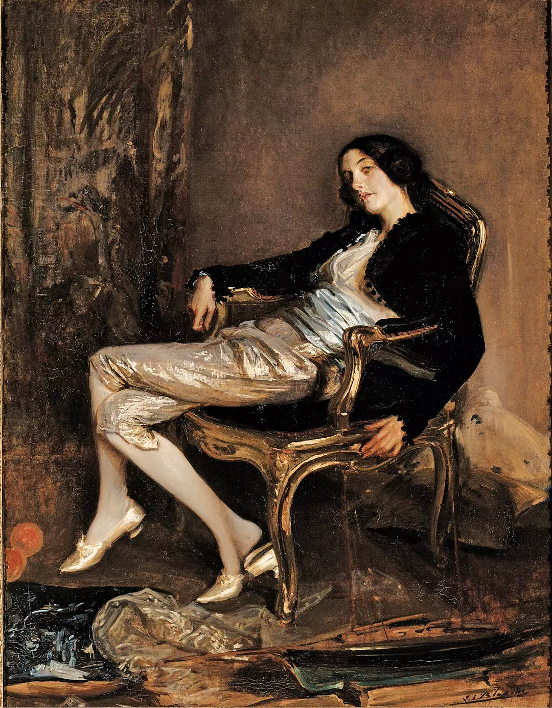

Jacques-Émile Blanche – Le chérubin de Mozart, Désirée Manfred (1903-1904) – Wikimedia Commons

In this portrait, artist Jacques-Émile Blanche paints his favorite model, Désirée Manfred, dressed up as Cherubino. She leans back in a relaxed position in her gilded chair with a sultry facial expression that confronts the viewer, popping the heel of her foot out of her satin slipper in a flirtatious manner.

Charlemagne-Oscar Guet -The Countess and Cherubino; from Beaumarchais’ Marriage of Figaro, c. 19th century – JSTOR

In a darkened room with the curtains drawn closed, a sensual moment is shared between the Countess, dressed in red, a color of power, and Cherubino dressed in white, a color of purity. Cherubino’s hat is discarded on the floor, perhaps knocked off by the Countess’s hand caressing his hair. This portrait may have been a reference foreshadowing Figaro’s sequel, Beaumarchais’ La Mère Coupable, where the Countess discovers herself pregnant with Cherubin’s baby! “Voi che sapete” must have worked!

Aimé Dupont – Emma Calvé as Cherubino (1917) – Wikimedia Commons

In this photograph taken by Aimé Dupont, French soprano Emma Calvé commands the viewer’s attention with direct eye contact and a flirtatious smirk. She holds her plumed hat in her hand, resting her hands on the arms of her throne-like chair to show off her lace and ribbon-decorated costume.

All three portraits share similar traits:

The Chair

In Act 1, the chair plays an important role in Cherubino’s character, as he famously hides behind a chair in Susanna’s room to avoid being seen when the Count barges into the room uninvitedly. When Don Basilio approaches the room, the Count also tries to avoid being seen “alone” in a room with Susanna, and Cherubino then scurries around to sit in the chair and hide underneath a sheet as the Count frantically hides behind the chair when Basilio enters the room. In these portraits, though, Cherubino reclaims the chair as an object of hierarchical status that gives him power and confidence, instead of using the chair as a device to hide behind.

The Costume

All three women dressed as Cherubino wear similar garments of a high-necked, long-sleeved blouse and/or jacket with ruched pants that are cropped at the knee or just above. Their shoes are delicate with a small heel and bow, and their garments are of lighter color palette, compared to the rich, deep red of the Countess’s velvet dress. In paintings, darker pigments such as deep red, royal blue, and dark purple were reserved for depicting royalty or people of higher status to indicate their social status, as they were also the most expensive and hardest to come by. Similarly, the red dye of the Countess’s dress in the Guet painting would also have been an indication of her status in the costuming of the opera (see Brianna’s Costumes page for more details!)

The Calves and Ankles

In all three portraits, the calves and ankles of each Cherubino are not only visible, but highlighted, either through light and shadow or through overt visual display. Even wearing tights or stockings, the cropped pants expose the contours of the legs, contributing to the sexual desire of Cherubino. In the 19th and 20th centuries, it would have been very risqué for a woman to show her calves and ankles, but when one is dressed as Cherubino, anything is possible!

Cherubino as Revolutionary?

Today, Cherubino is a role that intentionally plays with modern notions of gender and sexuality, in an opera underscored by political undertones, through dramaturgical interpretations that highlight the sexual ambiguity of the trouser role. With Cherubino and all trouser roles, it is important to ask whether they actually bend gender stereotypes, or if they just play into traditional gender roles? Just because a woman is playing the role, is it feminist? Or are we just stereotyping and heteronormalizing the experience of an adolescent, lustful boy? When trouser roles were first established, they gave female actresses and singers the chance to take center stage in a male, sometimes heroic role, and in Cherubino’s case, the chance to boldly assert their romantic feelings in a public setting. In that vein, it can be argued that trouser roles were indeed revolutionary to expand the performance canon and make room for women.

In their 1993 essay called “Critically Queer” published in GLQ: A Journal for Lesbian and Gay Studies, Judith Butler discusses gender performativity and drag culture, declaring that the undecidability of gender is “the play between psyche and appearance,” rather than being purely a psychic truth or a surface appearance.8 This methodology can be applied to the role of Cherubino, whose gender is defined by the written words in the libretto and score, but whose performance of gender differs each time the role is interpreted and performed by a different singer. In this sense, performing trouser roles encourages an exploration of gender, which speaks to the revolutionary nature of the role of Cherubino and the opera Le Nozze di Figaro as a whole.

Endnotes

for full citations, see Learn More

- Beaumarchais trans. Coward 2003, The Figaro Trilogy, 82. Emphases in italics by Emma Harrison. ↩︎

- Strohmeier 2002, “Pants Roles: Gender Fluidity and Queer Undertones in Opera.” ↩︎

- Rosselli 2001, “Castrato.” ↩︎

- Jander and Harris 2001, “Breeches part.” ↩︎

- Rosselli, “Castrato.” ↩︎

- Reynolds 1995, “Ruggiero’s Deceptions, Cherubino’s Distractions,” 140. ↩︎

- Reynolds, 141. ↩︎

- Butler 2003, “Critically Queer”: 24.

↩︎