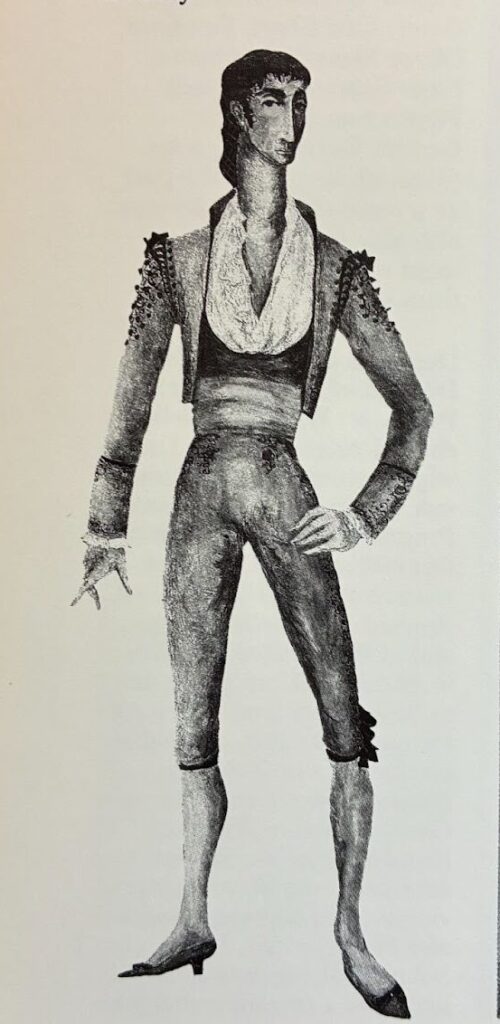

Figaro; Walter Gondolf (1965). “Figaro appears here as a class-conscious and rebellious servant who opposes the nobility”.

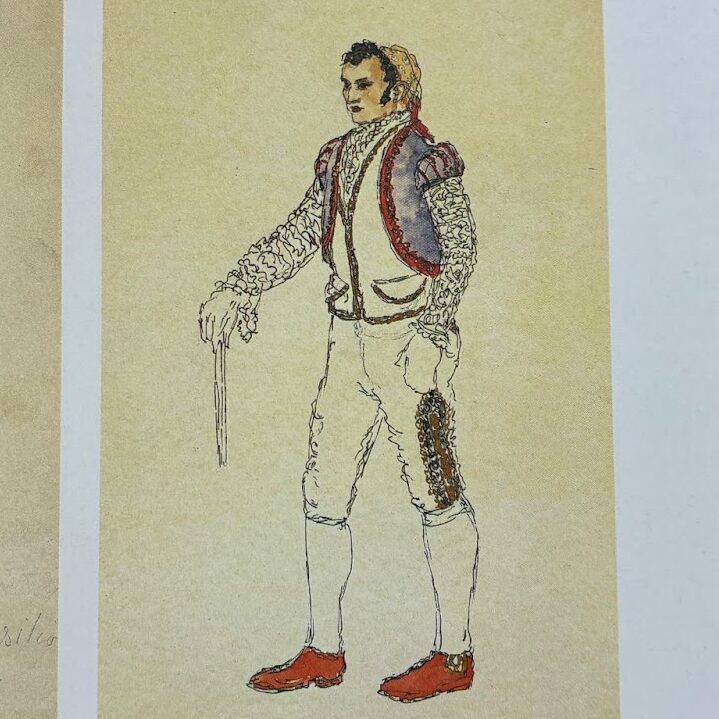

Figaro – Carl Mayerhofer (1870) – Wien Staatsoper

As illustrated in these various depictions of Figaro, his costume is perhaps the most consistent throughout the illustrations of his character. This is likely because he is the main character. Common themes seen in the above figures include his snood hat and somewhat Spanish attire, which are modest enough to indicate that he isn’t nobility. Beaumarchais’s character descriptions for The Marriage of Figaro read: “[Figaro’s] costume is the same as that worn in The Barber of Seville,” once again pointing to the early themes of recyclability and reusability in design, with more of an emphasis on the innovation of the music.

There was no strict attire requirement for how these characters would look. Rudolph Angermuller notes that “it is striking that there were no uniform costumes, and that the sets used for The Marriage of Figaro were also used in other works.” (Angermüller 1988, 140). However, at the end of the nineteenth century, as more and more opera production companies appeared across Europe, some standardized designs were created in order to meet the demand of opera.

Modern-day production design

Figaro’s “Wedding Attire”, Utah Opera, 2016

Utah Opera’s 2016 production of The Marriage of Figaro fitted Figaro in a suit for acts three and four of the opera. Their version depicted the story in 1915’s costumes. Figaro wears an Edwardian hat and dove grey suit, and is kept in grey clothes in each design to illustrate that he is lower class. The typical, “historically accurate” costume that Figaro would have worn famously fits Figaro in a snood and a Spanish-inspired blouse. This reimagined Figaro costume equates these elements to embody a reborn Figaro, who sings the same story but speaks a different artistic statement.

The Utah Opera production is certainly a different story from the historically accurate version. However, even the correctness of “historically accurate Marriage of Figaro costumes” is debatable. Since Mozart’s opera was rewritten so many times due to controversy, there is no singular production or “most original costume” that defines The Marriage of Figaro; however, there are standard conventions that most productions follow. These include Susanna’s bonnet, Cherubino being cast as a girl, the class divide representation through costume, and more.

In addition, retelling a classical opera to make a new creative statement is intentional. Many modern-day productions of classical operas redesign the costumes to fit a different time period, not necessarily to appear more modern, but to give the opera a new look.