Increasingly, Latin American students came in the 1940s and 1950s. In 1965, Mount Holyoke joined the Latin American Scholarship Program of American Universities which worked to combat the “brain drain” that often occurred when students departed their home countries for education abroad. Student scholars received full-ride scholarships in exchange for returning home and teaching four plus years at one of 106 Latin American universities.

This program allowed Ilse Accosta-Vargas (Costa Rica), class of 1968, and Amarilis Puello (Panama), class of 1969, to attend. Both gave interviews on their perspectives of the 1968 geopolitical scene for Professor Elizabeth Green’s course “Problems in Contemporary Newswriting and News Reading.”

“Regardless of how safe some of us felt after arriving in the U.S., or how well we were able to integrate into American society, the wars we left behind haunt us, and new wars force us to relieve painful and unforgettable experiences. We are compelled to face the dichotomy of our feelings for our native and adoptive countries. The invasion of Panama—the country where I grew up and my family still lives—filled me with anger over the actions of the U.S. government, concern for the safety of my family and friends there, and despair for the hundreds of families of those who died…or were left homeless and physically and psychologically scarred for life.” —Bessy Reyna (Cuba), class of 1970. Alumnae Quarterly, Winter 1992.

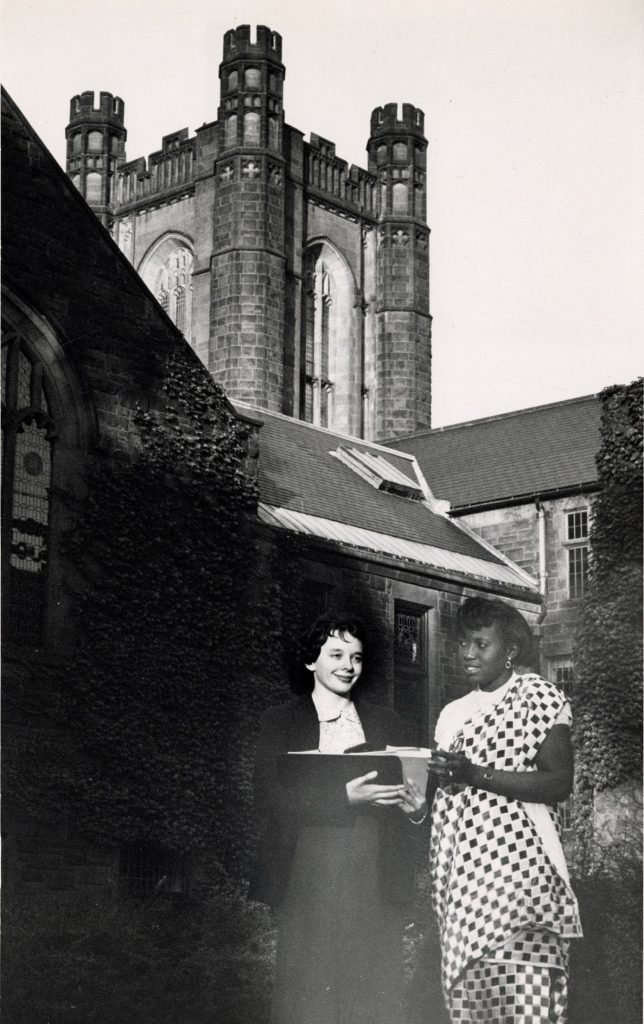

Although Mount Holyoke has historically stressed its commitment to international diversity, one long absence was the lack of African students. No students from Africa were enrolled at the College until after the mid-twentieth century. As decolonial movements swept through Africa in the 1950s and 1960s, many African nations cooperated in programs to develop qualified professionals abroad for nation-building objectives. In 1960, Mount Holyoke was among the first twenty U.S. colleges to enter the African Scholarship Plan for students of the African federation, and the African Scholarship Program of American Universities for students from sub-Saharan countries. However, many U.S. assistance initiatives were accused of being the latest brand of hegemonic influence and neocolonialism in the era of the Cold War.

“We need technical assistance and the Soviet Union has been stepping in and giving it. We are not ungrateful for aid we badly need, and perhaps this is why underdeveloped countries are so quickly termed ‘Communist.’” —Esther “Patty” Hadson-Taylor (Sierra Leone), class of 1962.

The Association of Pan-African Unity, previously the African-American Society formed in 1967, was open to all students of African descent, recognizing “the permanent bond affiliating black peoples across the globe.” Many African students at Mount Holyoke expressed solidarity with Black people in the U.S., regardless of national affiliation.

“One suffers when those with whom one identifies does so.” —Pat Mabeza (Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe), class of 1970.

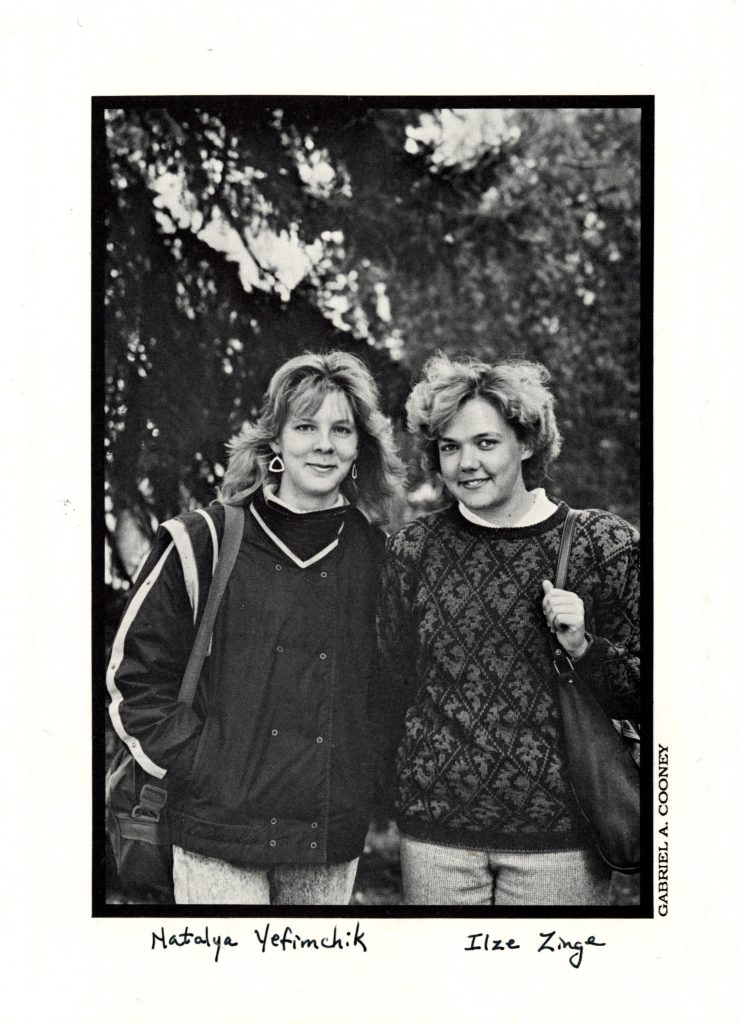

Pictured above, Soviet students Natalya (Natasha) Yefinchik (Belarus, formerly part of the Soviet Union), certificate student 1989, and Ilze Zinge (Latvia, formerly part of the Soviet Union), certificate student 1989, before their interview on NBC’s Today Show on January 3, 1989. These two students came to the College as part of landmark student exchange program between the U.S. and U.S.S.R. in 1988.

In 1988, for the first time fifty-six undergraduates from the Soviet Union (U.S.S.R.) attended college in the U.S. without political chaperones. Mount Holyoke was one of twenty-six liberal arts schools in the Collegiate Consortium for East-West Cultural and Academic Exchange to host Soviet students. This was a part of the largest group of exchange students to ever come to the U.S. from the U.S.S.R. — and signaled hope of easing geopolitical tensions.