Oh, Canada!

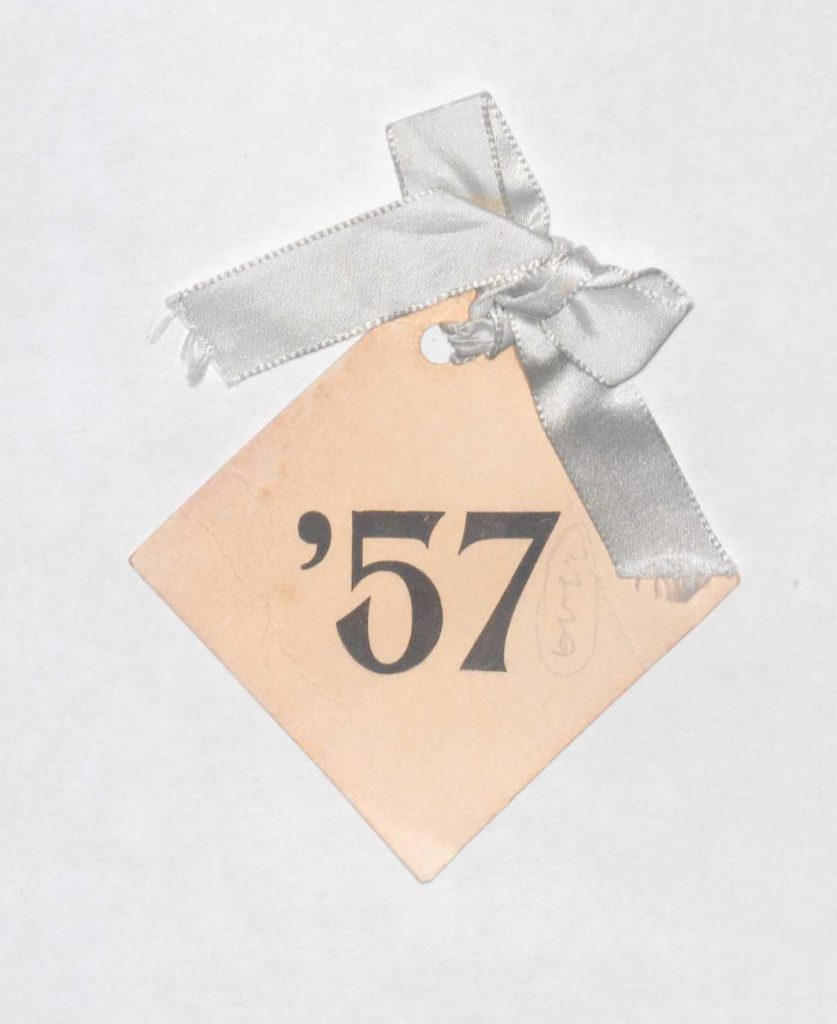

The first international students to join Mount Holyoke came from the United States’ neighbors to the North: Canada! Beginning in 1842 with Susanna Major, class of 1843, Canada started Mount Holyoke’s international student population, even when that population was in the single digits. Alice Parker, class of 1857, was one of three students from Nova Scotia to attend the Seminary in the same graduating class. She would write home about being “entertainment” for American students, describing nights where her fellow Canadian students would bring Americans into their room at night to answer questions about Nova Scotia. “The young ladies never tire of hearing about N.S.,” she wrote in a letter to her father in 1854. It would not be until the first international student from Japan, Toshi Miyagawa, class of 1893, came to the College that Mount Holyoke’s global community broadened.

What classifies as an international student?

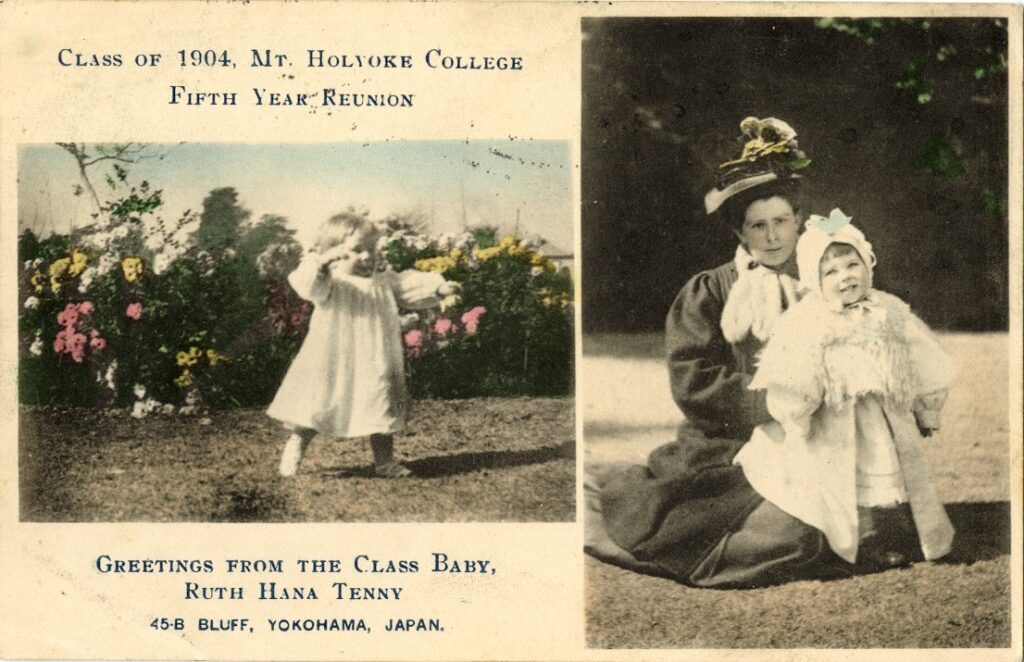

The case of Ruth Tenney, class of 1929, whose parents were missionaries in Japan, was not an uncommon one. Many Mount Holyoke alumnae from the 19th to the early 20th centuries embarked on missionary work abroad, especially to China. As a result, many of their children were born and raised abroad with American parents. The daughters of these women often attended Mount Holyoke and then returned to their birth country to live and work. Are these students “international” by contemporary definitions? Do they deserve a place in these cases as well?

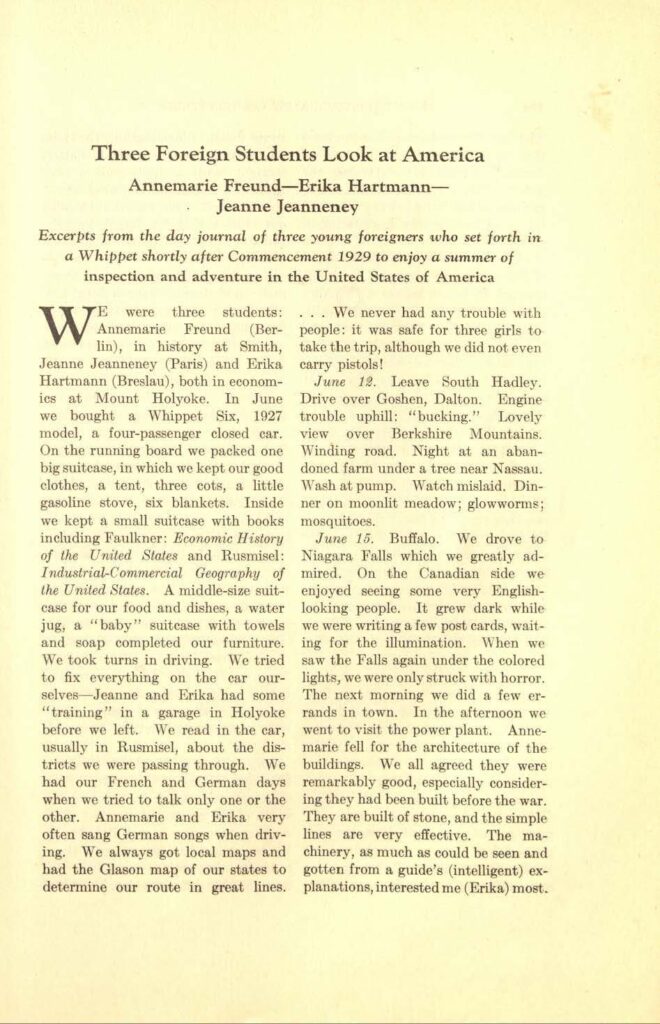

This journal of three international students shares their travels across the country in an automobile. The entries largely focus on exploring different state colleges and national parks. Their experiences include a lunch with Ruth Muskrat, class of 1925, an Indigenous alumna from Mount Holyoke, sleeping in a decommissioned syrup shed, and a meeting with one of Booker T. Washington’s sons. In an account of the trio’s attempts to purchase the car from a dealer, Freund inadvertently implies they may have stolen the vehicle by forging the notarization of a cash endorsement.

“Warp and Woof”

“Internationalism has been woven into the very warp and woof of this institution from the beginning.” – Mary Wooley, President of Mount Holyoke College from 1901-1937, speech at Mount Holyoke in 1932.

The institutional philosophy of “internationalism” has been entrenched at Mount Holyoke since its beginning. The College’s steady export of graduates who specialized in education and missionary work led to a network across the world. Alumnae were principals, Y.W.C.A officers, and other professions that were involved in the education of women. International students from the early 20th century often studied under alumnae before their arrival at Mount Holyoke. Throughout the late 1800s-early 1900s, the institutions and relationships formed by these alumnae paved the way for associated “daughter” schools, which were schools created by Mount Holyoke alumnae.

Early international students who had completed several years of higher education in their home country were often accepted to Mount Holyoke. These students often served as language assistants in several departments, notably French and German. The admission of international students under these conditions meant that there was some consideration given by the College to not admit too many students with certain language backgrounds. These students were the precursor to the Language Labs program that began in 1946.

Despite the proclaimed belief that internationalism was inherent to Mount Holyoke, early international students were often exoticized in the press. From detailing how “odd” their dress or mannerisms were, these pieces were often written by non-international alumnae for publications like the Mount Holyoke Alumnae Quarterly. On the rare occasion an international alumna would be asked about Mount Holyoke, she would be asked to write a piece that connects how her “foreignness” interacted with the domestic students.

Despite this alienation, international students maintained honor work and received campus-wide recognition for their time at Mount Holyoke. The following quotation, from a report by the Committee of Foreign Students in 1928, remarks on this:

“The foreign students find their college life here full of flavor and interest. Only one or two had serious difficulty with their work. Their presence in classes and the college residence halls has provided a real stimulus to broader and more tolerant thinking among their American fellow students.”

With this in mind, do you agree with President Wooley? Has Mount Holyoke’s commitment to internationalism been “a part of the warp and woof” of the College since the beginning? Or has this commitment unfairly placed a burden on international students to join a “global community” of Americanized peers?