Hailee Pitschke

Edited By Myra Zia (Senior Editor) and Asmi Shrestha (Junior Editor)

Abstract: The case of Kennedy v. Bremerton appears at first glance to refer to religious liberties for public employees. Though some might consider this case to be relatively inconsequential, the themes reflected in the Supreme Court’s handling of the case have major consequences for the future of the court as a whole. This article argues that the case of Kennedy v. Bremerton marks a significant turn in the court as blatant dishonesty about precedent and about the facts of cases is normalized. It theorizes that the erosion of the Establishment Clause’s strength in this case poses a threat to Obergefell v. Hodges in the concurrences written by Justices Alito and Thomas. Furthermore, it illustrates Justice Kavanaugh’s positionality as a swing vote on the court by analysing his dissenting opinion and strategic neutrality in the oral arguments. Most importantly, this article examines two key concerns emerging from this case. First, the court’s majority opinion completely ignored the precedent set by Lemon, significantly undermining the principle of stare decisis. Second, the court’s majority and dissenting opinions had distinctly different understandings of the facts. This article seeks to call attention to the erosion of basic principles within the court which jeopardize its legitimacy as a neutral institution.

Introduction

Kennedy v. Bremerton, 597 U.S. ___ (2022) is a case about religious freedom, the distinctions between public and private employees, and the First Amendment. The case expanded the right to religious expression for public employees at the expense of private citizens. Many would consider that, alone, to be an egregious miscarriage of justice. However, there are several equally if not even more concerning trends being reflected in this case, placing several more issues in complicated positions. Kennedy v. Bremerton (2022) brings light to a number of deeper trends within the Court, such as threats to the rights of the marginalized and strategic decisions getting in the way of honest intellectual discourse.

The Facts of the Case & Procedural History

The case of Kennedy v. Bremerton (2022) is an odd one, primarily because of the conflicting reports on the facts of what exactly happened. Joseph Kennedy, a Christian high school football coach at Bremerton High School, began praying after each football game at the center of the field, where students regularly joined him. Officials from the school district asked him to stop, with the explicit reasoning provided being concerns that the expression might be considered a violation of the Establishment Clause. The school board suggested he pray in private, and offered to find a private space for him to pray in. In a social media post, Kennedy expressed that he felt he would be fired for his refusal to comply, resulting in a media frenzy. Members of the crowd during subsequent games were reported to have knocked down members of the marching band and shouted at school faculty. Kennedy was placed on paid leave by the district, and Bremerton’s director of athletics recommended that he not be rehired. Kennedy did not reapply the next year.

Following leaving Bremerton High School, Kennedy would initially file in the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Washington, which ruled in favor of the school board. On appeal, the Ninth Circuit upheld the opinion. In March 2020, the District Court granted summary judgment in favor of the school district and, a year later, the Ninth Circuit ruled once again in favor of the school district. The Ninth Circuit then denied a rehearing en blanc. Certiorari was granted in January of 2022, finally sending the case to the Supreme Court.

Kennedy’s Case Meets the Court

Kennedy v. Bremerton (2022) was first introduced to the Roberts Court in 2019, when the court denied the petition for a writ of certiorari. The Ninth Circuit declined to hear the case en blanc, and Judge Diarmuid O’Scannlain disagreed with the panel, saying “[i]t is axiomatic that teachers do not ‘shed’ their First Amendment protections ‘at the schoolhouse gate’” referencing Tinker v. Des Moines, 393 U.S. 503 (1969). This would place the balance between Free Exercise rights for public employees and the Establishment Clause as the key issue facing the court.

The Court’s Justices

The Roberts Court possessed a clear conservative majority, which led to a large amount of public criticism. Historically, the Court has been meant to transcend political biases, but the Roberts Court has recently been critiqued for voting along political lines. Chief Justice Roberts and Justices Thomas, Alito, Kavanaugh, Gorsuch, and Barrett were all nominated by Republican presidents and have oftentimes voted as a unit. Justices Breyer, Sotomayor, and Kagan were all nominated by Democrats, and have also all voted as a singular block on many occasions. Due to the constant overturning of precedent and the appearance as a political entity rather than a just court, the Court’s sense of legitimacy has been eroded throughout recent years in the eyes of the public. Some would argue that Chief Justice Roberts, in particular, has appeared to be concerned about the appearance of the Court, as evidenced by the tactics utilized in the way the Court has addressed recent cases— especially this one.

The Issues Posed

In Kennedy v. Bremerton (2022), the Court was asked to strike a balance between rights. The school district sought to restrict Kennedy’s expression on the grounds that it may constitute a violation of the Establishment Clause. The Court was asked whether or not this was a justified restriction on expression. The Court had to further consider whether or not this restriction of expression was in violation of Kennedy’s Free Exercise or Free Speech rights. The issue boiled down to where the line between Kennedy’s right to free religious expression (as a public employee) and the students’ rights to be free from a state-established religion may be drawn.

The Court’s Opinions

The Majority Opinion

In a 6-3 decision that was divided perfectly along party lines, the Court held that “[t]he Free Exercise and Free Speech Clauses of the First Amendment protect an individual engaging in a personal religious observance from government reprisal; the Constitution neither mandates nor permits the government to suppress such religious expression.” By siding with Kennedy, the Court expanded protections for religious expression further in the case of public employees, at the expense of students’ right to be free from coercive religious practices in school.

The majority opinion,written by Justice Gorsuch, differentiated between this case and other school prayer cases by claiming that the “prayers for which Mr. Kennedy was disciplined were not publicly broadcast or recited to a captive audience” and that “[s]tudents were not required or expected to participate.” The majority opinion emphasized that at the time Kennedy led his prayers, other members of the coaching staff could “do things like visit with friends or take personal phone calls,” meaning that Kennedy’s actions took place outside of his capacity as a coach. Therefore, Kennedy’s prayers were acts of private, personal expression.

The majority’s opinion continued on to frame the application of the Establishment Clause in this capacity as anti-religion. Justice Gorsuch wrote that there is “no historically sound understanding of the Establishment Clause that begins to ‘mak[e] it necessary for government to be hostile to religion’ in this way.” The prevailing notion expressed in this decision is one that frames restrictions for public employees’ religious expressions within schools as inherently anti-religion. This sentiment carries throughout the opinion and forms the basis for the Court’s argument that Kennedy’s rights were infringed upon by the school board. According to the majority opinion, the imposition of restrictions by the government onto public employees regarding “private, personal prayer” stands in violation of that employee’s rights.

The Dissenting Opinion

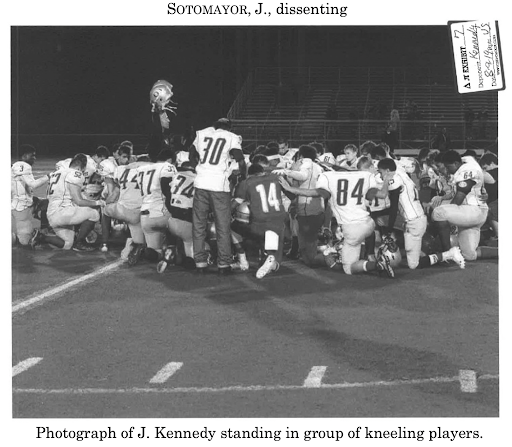

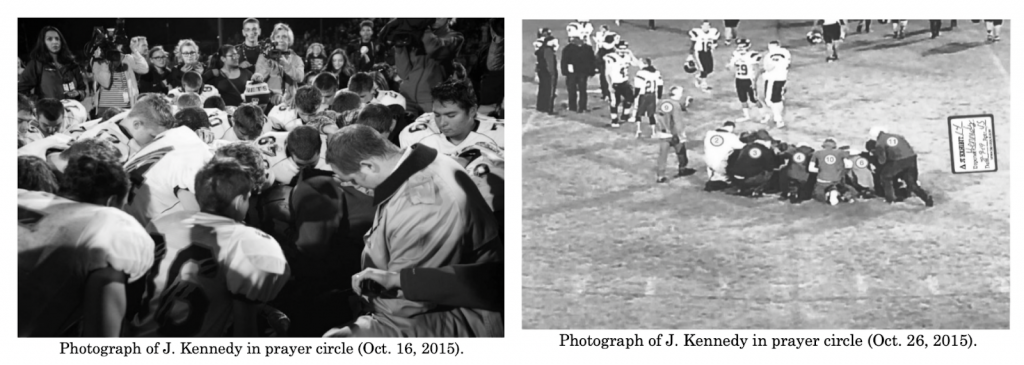

Justice Sotomayor was joined in her dissent by Justices Breyer and Kagan. Her dissent is particularly unusual because she includes photographs and for the reasoning behind their inclusion. The inclusion of the photographs function as a logical argument typically would in a dissenting opinion, being used to substantiate her argument. In this case, the dissent involves contradicting the majority opinion’s version of events just as much as it involves engaging in the logical, legal arguments being discussed in the majority opinion.

Justice Sotomayor’s dissent focuses heavily on the majority opinion’s description of the unfolding of the events. She states that “[t]o the degree the Court portrays petitioner Joseph Kennedy’s prayers as private and quiet, it misconstrues the facts.” She includes photographic evidence as if to ask the public to evaluate for themselves whether or not the description of Kennedy’s prayers as private or personal had been in good faith. By including the photos, Justice Sotomayor does her best to hold the majority opinion accountable for their inaccurate description of the prayers. Rather than simply having a back-and-forth written description, which many may write off as a he-said she-said situation, Justice Sotomayor’s incorporation of photographs begs the readers, the public, and the opposition to explain themselves, asking the reader to make their own evaluations based upon the evidence that she is presenting. This makes Justice Sotomayor’s dissent particularly damning in the historical record.

This engagement with the misrepresentation of the facts does not prevent Justice Sotomayor from pointing out the consequences of the Court’s decision. She specifically emphasizes the ways in which this decision could harm young people, who are “particularly vulnerable to coercion.” Justice Sotomayor describes the Court’s decision as setting us “further down a perilous path in forcing States to entangle themselves with religion, with all of our rights hanging in the balance.” She cuts particularly deeply at the manner in which this decision prioritizes “the religious rights of a school official, who voluntarily accepted public employment and the limits that public employment entails, over those of his students.”

The Concurrences: Justices Thomas and Alito

Justices Thomas and Alito both wrote separate concurrences, making very similar points. In essence, they both point out that the Court has failed to set a clear standard regarding the balance of rights the case confronts. Justice Thomas directly addressed how “the Court refrains from deciding whether or how public employees’ rights under the Free Exercise Clause may or may not be different from those enjoyed by the general public.” Secondly, Justice Thomas claimed that the Court failed to define what “burden a government employer must shoulder to justify restricting an employee’s religious expression.” While the latter may be an important point by Justice Thomas’ count, the former question is the more glaring omission in the Court’s majority opinion, and it’s similar to the one that Justice Alito also pointed out in his concurrence “[t]he Court does not decide what standard applies to such [Kennedy’s] expression under the Free Speech Clause but holds only that retaliation for this expression cannot be justified.” Overall, both concurrences point to a lack of clarity that emerged from the Court’s decision, wherein they left several key questions entirely up in the air.

Take-Aways

While the case of religious expression in schools is important in and of itself, Kennedy v. Bremerton (2022), when positioned within the Court’s wider context, reveals several potential trends that have much broader implications for the Court’s future.

Concurrences & The Court’s Future

Justices Thomas and Alito joined the majority opinion and, additionally, wrote separate concurrences. Justice Kavanaugh’s decision was to side with the majority opinion in all except for section III-B. While the two written concurrences were short, and while Justice Kavanaugh gave no reasoning for his decision, examining the underlying thought processes of Justices Thomas, Alito, and Kavanaugh can shed light on their visions for the future path of the Court.

Threat to Obergefell

In Justices Thomas and Alito’s separate concurrences, both pointed to areas in which the majority opinion failed to set clear standards pertaining to the rights of public employees. While it may appear at first a bit convoluted, I think that Justices Thomas and Alito are positioning the Court in such a way as to threaten Obergefell v. Hodges, 576 US _ (2015). Many would argue that the majority opinion elevates (in the case of public employees) religious expression over other forms of expression. A more expansive view on the rights of public employees to free exercise, paired with Justices Thomas and Alito’s propensity for overturning and undermining precedent, as well as their previous dissents in Obergefell v. Hodges (2015) brings a specific conservative legal strategy to mind.

Post-Obergefell v. Hodges (2015), a columnist for the Washington Post wrote “public officials arguably have fewer religious liberty protections than do… private citizens, at least when serving in their official capacities.” She continued on, writing that “[s]ame-sex marriage opponents like to claim that public officials are entitled to reasonable accommodation of their religious beliefs.” In the wake of Obergefell v. Hodges (2015), there was a notion that clerks, as public employees, had a right to not issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples on the grounds of having religious objections. By pointing out the gray area the Court left regarding public employees’ free exercise rights, Justices Thomas and Alito could be pointing out a potential future in which these clerks’ rights to free exercise are placed above the rights of same-sex couples.

Kavanaugh’s Caveats

Justice Kavanaugh joined the majority opinion of the Court, except for Part III-B. During oral arguments, Justice Kavanuagh asked some hard questions “[w]hat about the player who thinks, if I don’t participate in this, I won’t start next week? Or the player who thinks, if I do participate in this, I will start next week?” Whether he actually wanted an answer to his question or not, Justice Kavanaugh has clearly been positioning himself to appear as the moderate on the Court, likely seeking a swing vote role. Justice Kavanaugh wrote no separate concurrence, and did not explain the rationale behind his issue with the section he did not join, meaning that no one knows “whether he disagreed with the majority’s approach (applying Pickering to a claim involving religious speech), disagreed with the outcome of the Pickering test as applied here…, or deemed it unnecessary to decide.” So why did he do it? It is possible that it was a strategic decision to signal to either the public or to the rest of the Court that he’s not solidly with the conservative block—he could be the Court’s swing vote. Kennedy v. Bremerton (2022), therefore figures into the discussion about the Court’s future balance.

Blatant Intellectual Dishonesty in Two Flavors

The most frightening aspect of this case is not the erosion of the Establishment Clause, rather it’s the precedent it sets by allowing for blatant dishonesty in the Court. This dishonesty comes in two distinct flavors, both threatening the institutional integrity of the Supreme Court.

Dishonesty Regarding Facts

In this case, “the majority opinion and the dissenting opinion framed the facts entirely differently.” Was Kennedy’s prayer private or public? Was it disruptive or quiet? The discrepancies in descriptions are significant and play directly into the decision. Julie D. Pfaff did an analysis of the majority opinion’s claim that Kennedy’s expression was decidedly private, and found that Kennedy’s numerous televised interview appearances gave “credence to the dissent’s version of the facts surrounding the public nature of the October 16th prayer.” The two descriptions of the facts cannot both be held as true simultaneously.

By misrepresenting facts, the majority opinion was able to give the opinion they wished to give, engaging with a version of the case that is not based fully in reality. The conservative block’s attempt at maintaining institutional integrity hinged upon their engagement with the facts as they wished the facts had been, rather than how they actually were. This remolding of reality in the Court’s opinion sets a dangerous precedent, and cannot go entirely unchecked.

Dishonesty Regarding Precedent

The second layer of dishonesty comes in the form of Justice Gorsuch’s statement that “this Court long ago abandoned Lemon.” While “previous Supreme Court cases had criticized Lemon and disavowed the test as controlling law in some areas… Kennedy now makes clear that Lemon and its endorsement test are not the controlling law in any context.” Regardless of whether or not the Court had previously begun to move away from Lemon v. Kurtzman 403 US 602 (1971), the ruling in Kennedy v. Bremerton (2022) was, essentially, an overturning. The Roberts Court has faced such backlash, such a loss of institutional faith in the eyes of the public, that they appear to be too shy to call a spade a spade. Instead, they’ve chosen to claim that they aren’t overturning anything, because it had already been effectively overturned. Beyond just being an act of avoidance, an attempt to save face by shying away from the reality of their opinion, this could give lower courts an implicit go-ahead to ignore precedents that they don’t agree with on the basis that it has been long abandoned. In this sense, the deceit regarding precedent is tantamount to an opening of Pandora’s box when it comes to the potential consequences within the lower courts.

Conclusion

Kennedy v. Bremerton (2022) has marked a fundamental shift in the Court’s view of religious rights. Previously, public employees’ free exercise rights did not extend so far as to infringe upon the rights of private citizens under the Establishment Clause. Now, that tide is turning against the private citizens. The rights of public employees to stage religious demonstrations are being placed above the rights of students who are required by law to attend school. Beyond the immediate consequences, the various narratives within the case have shed light upon problematic trends within the Supreme Court. From concerns over threats to the rights of same-sex couples to bids for the coveted swing vote position to deceit becoming a potential new tool for the Roberts Court, the uniquely illuminating case of Kennedy v. Bremerton (2022) sheds light on the potential trajectory of the Supreme Court.

Bibliography

Barclay, Stephanie H., “The Religion Clauses after Kennedy v. Bremerton School District,” Iowa Law Review 108, no. 5 (July 2023): 2097-2114.

Howe, Amy. “In the Case of the Praying Football Coach, Both Sides Invoke Religious Freedom.” SCOTUSblog, April 24, 2022. https://www.scotusblog.com/2022/04/in-the-case-of-the-praying-football-coach-both-sides-invoke-religious-freedom/.

Pfaff, Julie D., “The Supreme Court Fumbles School Prayer in Kennedy v. Bremerton School District,” Atlantic Law Journal 26 (2023): 110-163

Kennedy v. Bremerton School District, 139 S. Ct. 634 (2019)

Kennedy v. Bremerton School District, 4 F.4th 910 (Ninth Circuit 2021).

Kennedy v. Bremerton School District, 443 F. Supp. 3d 1223 (W.D. Washington 2020).

Kennedy v. Bremerton School District, 597 U.S. ___ (2022).

Kennedy v. Bremerton School District, 869 F.3d 813 (Ninth Circuit 2017).

Kennedy v. Bremerton School District, 991 F.3d 1004 (Ninth Circuit 2021).

Lemon v. Kurtzman 403 US 602 (1971).

Obergefell v. Hodges, 576 U.S. ___, (2015) (Thomas, J., dissenting).

Obergefell v. Hodges, 576 U.S. ___, (2015) (Alito, J., dissenting).

Rampell, Catherine. “Opinion | on Same-Sex Marriage, County Clerks Can’t Exempt Themselves from the Law.” Washington Post, July 9, 2015. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/county-clerks-dont-decide/2015/07/09/b9922682-2676-11e5-aae2-6c4f59b050aa_story.html.

Slate. “Kavanaugh Questions.” www.youtube.com, April 25, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=955naEi8ks8&t=3s.

Stephanie Taub and Kayla Ann Toney, “A Cord of Three Strands: How Kennedy v. Bremerton School District Changed Free Exercise, Establishment, and Free Speech Clause Doctrine,” fedsoc.org, March 9, 2023, https://fedsoc.org/fedsoc-review/a-cord-of-three-strands-how-kennedy-v-bremerton-school-district-changed-free-exercise-establishment-and-free-speech-clause-doctrine.