The American School for Girls

Monastir was first occupied as a mission station in 1873. The American School for Girls was opened by Kate M. Jenney in about 1878. It was very small at first, with 15 boarding students and 30 day scholars.

Together the students studied religion, algebra, physiology, botany, geology, English, and Bulgarian, among other subjects. Mary Matthews wrote that of the students who attended the school, there were seven nationalities represented: “26 Bulgarians, 3 Albanians, 1 Greek, 5 Roumanian, 1 Serbian, 3 Gipsey, and 1 Jew.” There was a maximum capacity of 25 boarders at a time attending the school with day pupils numbering about twice that. Students came from Monastir or as far away as a day’s worth of travel.

Notable graduates included Effa Busheva, Athena Delinusheva, Parashka Stamenova, and Yordanka Beleva. Busheva was a teacher in the Macdeonian region for over 40 years, under the Monastir Mission’s name. Delinusheva was in charge of the Mission Orphanage for several years, became a translator at Ellis Island for over 25 years and spoke over seven different languages. Stamenova was an assistant teacher at the Monastir school. She later trained in Canada as a nurse. Finally, Beleva had quite a dramatic time at school. In her senior year at the school she led a strike and then was forced to leave the school. A year later she apparently repented and joined the Christian community.

During the World War I years, the school’s activities carried on, albeit greatly disturbed. Mary Matthews, by 1916/1917, was the only American missionary in Monastir. Rada Pavlova, her Bulgarian assistant teacher and friend, could not remain at the school after Monastir was returned to Serbia due to her heritage. In 1920, Matthews left the school, which was taken over by Beatrice Mann. Post-1921, however, the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions dropped work in that region. From then on it became difficult to find teachers and keep the school open. It closed around 1924, at the end of Mann’s five-year term.

Monastir and the Balkan Region

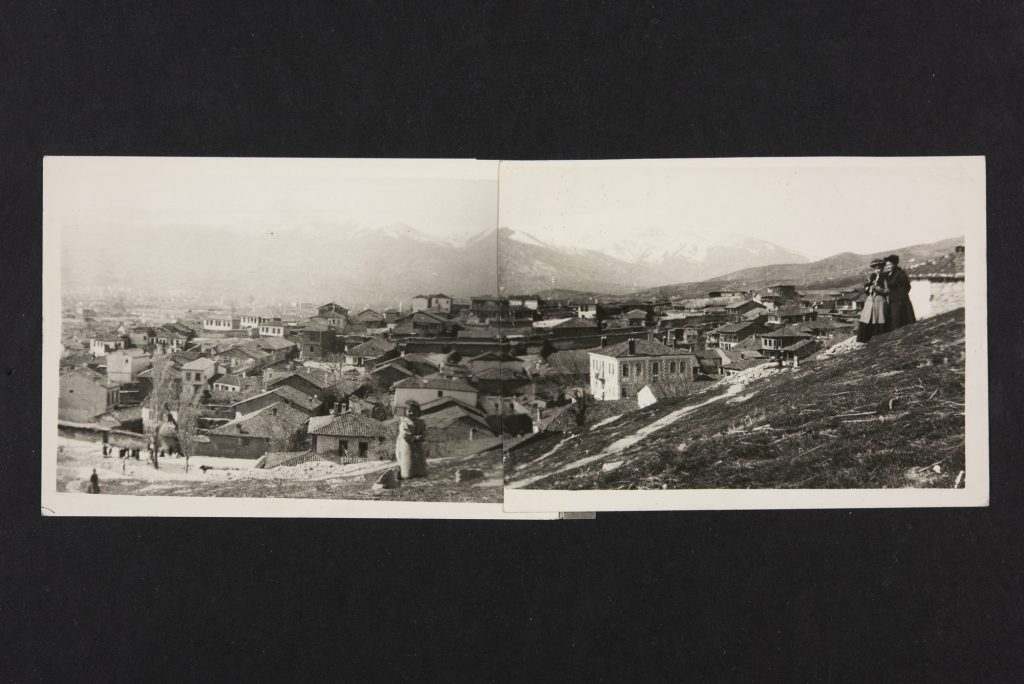

The American School for Girls was situated in Macedonia — a term which at the time did not refer to today’s Republic of Macedonia but rather a region. (Mary compared it to the concept of New England.)

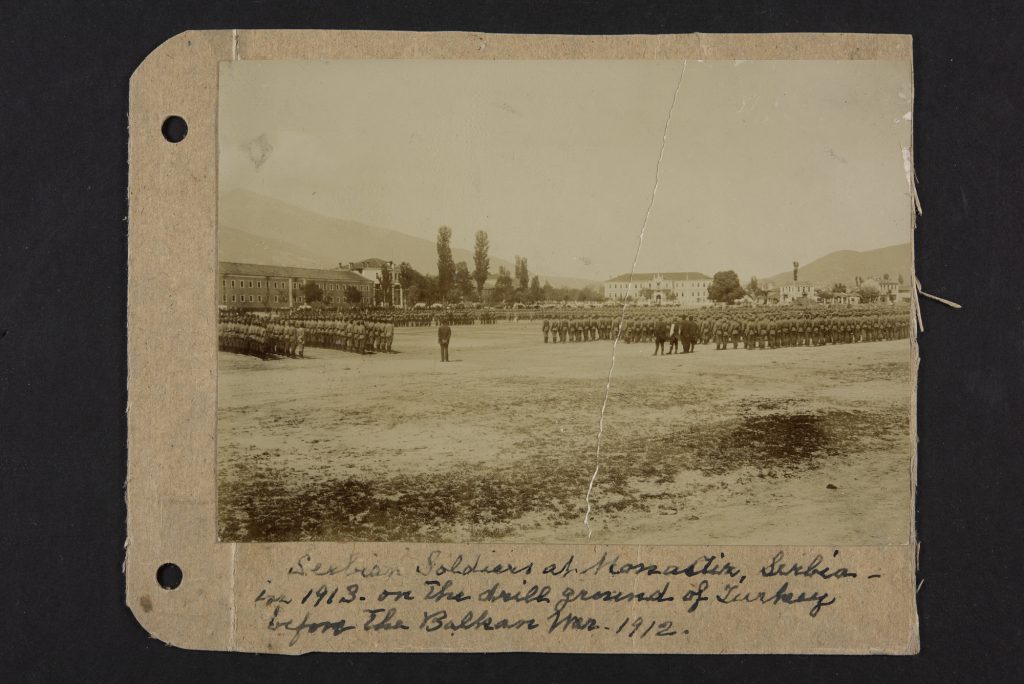

At the time Mary arrived in this region in 1888, Macedonia was considered part of European Turkey by American missionaries, up until such events as the Young Turk Revolution in 1908 and the First and Second Balkan Wars rendered countries such as Bulgaria, Serbia, and Greece to be independent entities.

The city of Monastir itself lay in the Pindus Mountains of Macedonia, on a wide plain surrounded by peaks — including the highest, Mount Pelister. Pelister was once green and forested, until all the trees were taken as fuel. In terms of population, Monastir was fairly varied. In Matthews’ early years, she estimated that the city’s population was about half Turks, three thousand Jews, and the rest a mix of Bulgarians, Greeks, Albanians, Romanians, and “Gypsies”. Over the course of Matthews’ time there, the city would change governmental hands at least three times. Monastir is now known as Bitola/Bitolje in the present-day Republic of Macedonia.

War and Conflict

Mary Matthews took a furlough to the United States in 1913. When she returned, she barely made it back to Monastir before travel opportunities seized up. “It was necessary to stay two years [in the United States],” Matthews wrote, “and I returned in September 1915, just in time to get into Monastir before the World War reached Serbia. By November, the way from Salonica was closed, and the Armies of the Central Powers, Germany, Austria, Bulgaria had covvered all of Serbia and occupied Monastir after severe battles on the plains for five weeks.” Overseas travel had also been a struggle, due to the increasing threat of war boats.

By 1916 Delpha Davis and Rada Pavlova — who had been Mary’s teaching assistants over many years — departed Monastir for New York. This left Mary virtually alone in the Monastir Mission. She attended to many different women and children during the war years with courage and determination.

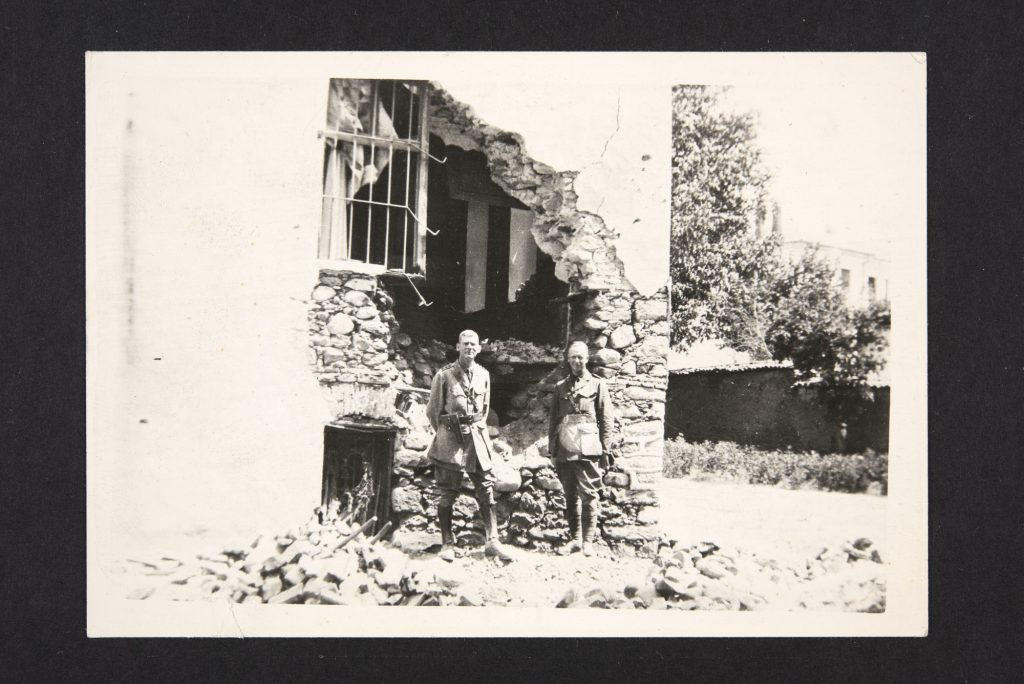

Mary and her remaining companions fared relatively well, apart from some close calls (an explosion while all the students were occupied elsewhere, an unexploded shell in the front yard, which remained lodged in a tree for a long time…). However, they were not without their own tragedies.

Mary wrote at this time, “Suddenly, without any warning, [a shell] fell into the street near the house. The windows of the large room where we were upstairs were shattered. I thought we three were safe and that it was a wonderful deliverance. I looked at Mrs. Harley..and she seemed frightened and unable to speak. I looked again and saw blood on her forehead. A bit of shell or of glass had entered her head quite deeply. [The French Hospital] was kind and tried to operate at once, but Mrs. Harley died at that time, about half an hour after she was struck.”

Monastir changed political hands twice over the course of World War I. The first event was the Bulgarian invasion of Monastir in November 1915. Despite the invasion factor, Mary described the situation as “safe to go about the city,” with order being maintained. A year later, however, the Serbian army (aided by British and French forces) took Monastir back from its Bulgarian conquerors. The Bulgarian/German/Austrian troops were forced to retreat to the mountains, from which they shelled Monastir for 22 months. These shells occasionally hit the American missionary property.

Whether or not Monastir was under Bulgarian control or Serbian control often caused varying struggles for the American School. German or French soldiers (depending on who held the city at the time) would sometimes attempt to requisition missionary buildings for their own purposes, such as supplying their horses or boarding troops and staff. Mary also had to be careful with how she presented the school — at one point, she moved an American flag from its flying post and put it in the front window, so that it could not be seen in the air by bombers.