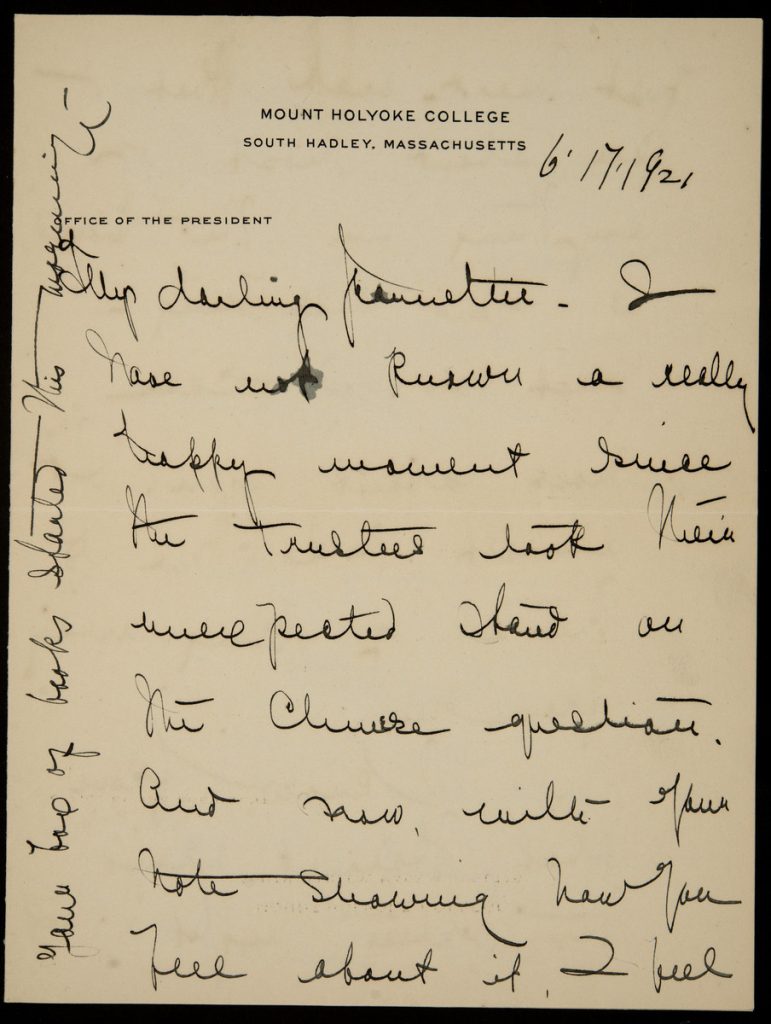

“And now, with your note showing how you feel about it, I feel just heart-sick. What I care about most of anything in the world, is your well-being — just as I care most about you. It almost kills me to think of being away from you…” – Excerpt from this letter, sent by Mary Woolley to Jeannette Marks on June 17, 1921. (Read the full transcription)

With the ratification of the 19th Amendment to the US Constitution on August 18, 1920, Mount Holyoke and its supporters entered a new era of opportunities for women. Incoming students took their right to education and access to institutions for granted, a fact that did not impress President Woolley or her contemporaries, themselves founders and supporters of these movements.

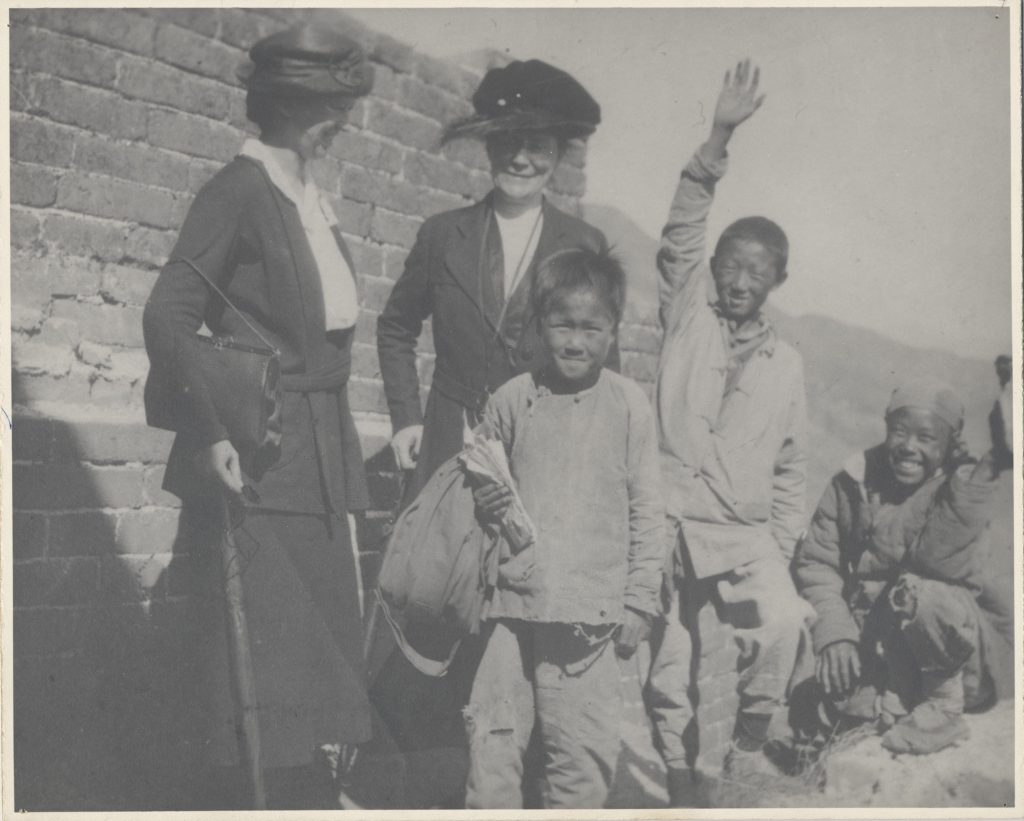

Mary Woolley was invited in the spring of 1921 to serve on the China Education Commission to study Christian missionary schools in that country. This would mean an extended absence in the fall and winter from Mount Holyoke and from Marks. The two discussed without serious intent the idea of Marks accompanying her abroad, but when Woolley departed on August 12, 1921, it was without her companion. Marks chaired the English Literature department and enjoyed the freedom of an empty President’s House.

Woolley was welcomed back to campus in February of 1922 with much fanfare. Students lining the road sang songs composed for the occasion and Marks had orchestrated the decoration of the couple’s four collie dogs with bows.

Woolley was delighted to find that in her absence Marks had truly and finally taken ahold of the English Literature department. Tensions between Marks and her colleagues remained high, with letters containing veiled threats exchanged from across rooms and disagreements aired to the President in hopes of favorable resolution.

Miss Marks and Miss Woolley’s professional lives were intertwined so thoroughly with their private life together that Marks’ antics were often viewed as reflective of Woolley’s treatment of her. Few questioned the judgement or tolerance meted out by the school’s beloved President, but those involved viewed Marks as a temperamental force who held great influence on the opinion of the College administration.

Their work at the school continued; Marks began teaching a highly coveted playwriting class that met in her very own “Attic Peace” study. Woolley spoke publicly about her time in China, armament, and the modernization of the college woman.