When thinking about money in a historical context, it is easy to separate it from the ways in which individuals understood, used, and altered money in their daily lives. This page seeks to unpack how real people and communities interacted with money in their respective cultures, time periods, and political systems. Four money objects from the Mount Holyoke Art Museum collection are put in conversation in this project; a Spanish silver with Chinese chopmarks coin, a counterfeit ten dollar shinplaster, a suffragette countermark coin, and a pair of earrings made from ancient coins. All these objects have very different histories that explain their production and particular uses, but all speak to the similar theme of how money fits into the everyday lives of people.

Firstly, the silver coin shows how people dealt with a fast changing and globalizing world. At the time, Spanish silver was used across globe, and the marks made by moneychangers in China made this silver trustworthy and usable in the market. The theme of trust continues with the counterfeit shinplaster, in a time of political instability in antebellum America, individuals had to trust (or not) each other based off split decisions. The suffragette coin also speaks to the political climate of a certain time and region. It gives insight into the political tensions of the radically changing Victorian era. Finally, the ancient coin earrings shows a different way in which money is used in everyday life, one of complete divorce with money’s economic role.

8 reales of Charles IV with Chinese Chopmarks, 1791 (MH 2017.3)

An examination of this 8 reales coin reveals the global network of money in the 18th century but also the people involved in the creation, alteration, and use of this coin. It’s a colonial-Spanish coin, covered in Spanish iconography, with an image of the Spanish king Charles IV on the obverse. It was made of silver mined in colonial-Mexico, was minted in Mexico City, and was later circulated in China. From the beginning, miners and minters in Mexico labored to produce this coin for the colonial Spanish government, before it was brought to China, probably via the Manila galleon. Once in China, a money-changer would have been involved to check its authenticity and create the coin’s chopmarks before it circulated in China. This system of chopmarked coins in China created new symbols of trust that deviated from the iconographies of Spanish minting authorities.

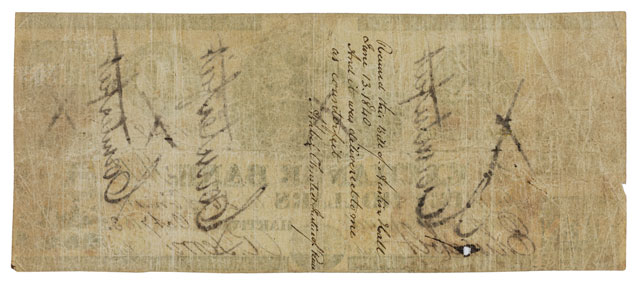

Counterfeit Ten Dollar Bank note, 1832 (MH 2019.4)

This Counterfeit Ten Dollar Bank note, created in 1832, is a phenomenal encapsulation of the extraordinary complexity of American monetary life in the antebellum period. In the early 19th century the United States lacked a centralized banking authority, and consequently a standardized currency system, with only gold and silver being legal currency. This is not to say, however, that the United States had a shortage of banks. They were exceedingly easy to create, and each individual bank often produced its own bank notes – a “shinplaster”. Countless numbers of these “wildcat” banks shared the economic landscape with more traditional banks managed by state or local authorities, as well as wealthy merchants and groups. This system was rife with counterfeits and governed by interpersonal trust – a trust clearly broken here, with a note marked “counterfeit” at all sites of detected forgery.

Crown with Suffragette countermark minted under Victoria I, 1892/1905 (MH 2019.20)

This object is a Suffragette countermark on a coin minted under Victoria I, the coin was minted in 1892 and the countermark was engraved in 1905. The obverse of the coin depicts Queen Victoria’s portrait of the original coin, with the words ‘Votes for Women’ engraved over her face. On the reverse, there is a man on a horse which is apart of the original coin, with the signature of those who committed this defacement crime, WSPU which stands for Women’s Social and Political Union. The suffragette movement engraved coins to disseminate their message broadly while also challenging the authority of the government denying them political equality. The WSPU committed other, more serious crimes for their cause such as arson and bombings. This coin gives an insight into the everyday political tensions of Victorian England.

Pair of earrings made from ancient coins, 20th century (MH 2021.5.12)

This 20th century Afghan earrings included in our collection is a prime example that encapsulates the repurposing of currency as a tool for personal adornment. In the 1950-60s, the nation was going through a period of transition towards democracy that brought forth issues of women’s rights. The abolition of the purdah system in the 1950s itself marked a turning point, allowing for increased opportunities for women in employment. The fact that these earrings were minted within the same timeframe could suggest that the repurposing of ancient coins into jewelry was not only a creative choice but as a broader statement about the evolving roles of women in Afghan society. To support this narrative, a distinctive cultural practice is found within Afghanistan that repurposes coins into jewelry. The Kuchi Tribe known to make Kuchi jewelry highlights a significant role played by women in the creation of these pieces. This role of women in jewelry making can be seen as a subtle form of resistance against traditional gender roles. The repurposing of these coins into jewelry then can be viewed as a propaganda against oppressive systems at that time, shifting the meaning of ‘coins’ and ‘currency’ its government denominations to cultural identity and expression.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.