National Activism in the Early 19th Century

The 1848 Seneca Falls Convention is widely considered the beginning of the women’s suffrage movement with its status as the first women’s rights convention, although stirrings of the movement existed in the decades prior. Even there, women’s suffrage was a divisive issue, although attendees were generally in agreement with other tenets pushed by organizers, including women’s property rights and access to education. Many prominent women’s rights figures were involved in the abolitionist movement but within those spaces, women’s voices were silenced and prompted organization for women’s right to vote. For this reason, Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton organized the first Convention, which would be succeeded by several more in the next two decades. In place of the eleventh Convention, the American Equal Rights Association (AERA) was founded in 1866 with the goal of enfranchising women and African Americans.

Tensions over the proposed 15th Amendment (which passed in 1870, granting Black men the right to vote) caused the AERA to collapse and the women’s suffrage movement to divide into two separate organizations. The all-women National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), formed in May 1869, opposed the 15th Amendment unless it also enfranchised women, and advocated for a federal suffrage amendment. Their platform broadly focused on national gender equality, including at the time radical views of divorce. Six months later in November 1869, the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA) was created, which offered membership to both women and men. They supported the 15th Amendment as progress toward universal suffrage and focused their efforts on securing women’s suffrage within each state. As the NWSA began to abandon some of its more polarizing beliefs in order to prioritize women’s suffrage, their values increasingly aligned with the AWSA. United in their goal of women’s suffrage, the two organizations merged to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) in 1890. Racism still persisted within the NAWSA — Black women were often excluded from participation in local chapters, and faced difficulty in registering to march in the 1913 Woman Suffrage Parade in Washington, DC.

Early 19th Century State and Campus Activism

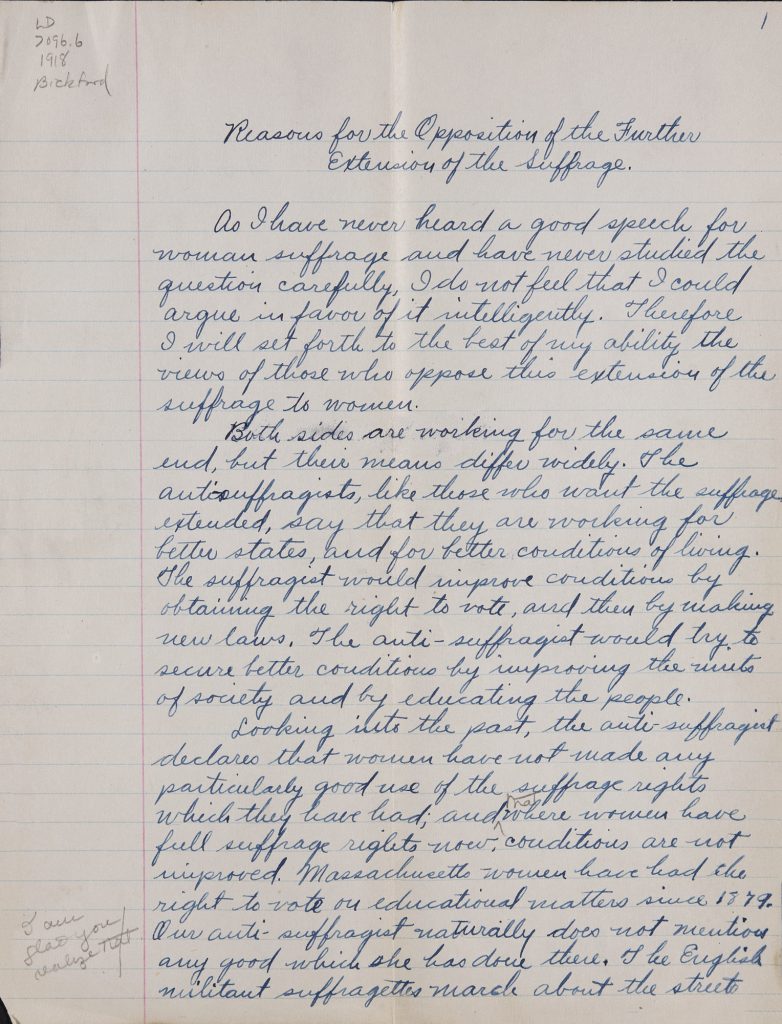

Meanwhile, Massachusetts prepared to conduct a vote for women’s municipal suffrage in the 1895 state election. In 1879, Massachusetts women had been granted school suffrage (the ability to vote for their local school committee), although this still disenfranchised women who couldn’t afford the poll tax. Municipal suffrage would grant women the right to vote in their local town election but not at the national level. Nearly 600,000 women who were eligible for school suffrage were permitted to vote in the municipal suffrage referendum with a special ballot, but only about 25,000 participated. This minimal turnout (approximately 4% of women) was largely due to anti-suffragist propaganda which claimed that voting was unwomanly, so anti-suffragists were better off refusing to vote rather than voting against. However, the majority of women who did vote were in favor — most Massachusetts men were diametrically opposed. Mirroring the state referendum, Massachusetts women’s colleges took up a mock vote among their student bodies. Student letters from this time reveal that while Smith and Wellesley were largely pro-suffrage, Mount Holyoke students at the turn of the century held predominantly anti-suffrage beliefs.