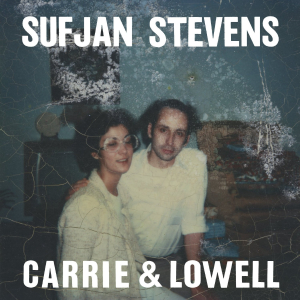

“Jesus I Need You”: A Review of Sufjan Stevens’ Carrie and Lowell

May 3, 2015

Rochelle Malter

Death With Dignity, the first track on Sufjan Stevens’ newest album, Carrie & Lowell, opens fittingly with Stevens plaintively singing “Spirit of my silence I can hear you/But I’m afraid to be near you/And I don’t know where to begin.” This perfectly introduces an absolutely gorgeous album in which Stevens, despite not knowing “where to begin”, explores human sadness, connection, and faith in a way that is deeply emotional. Through his unflinchingly honest examination of his relationships with his mother, lovers, and God, Stevens creates a work of art that is not only relatable but that also inspires personal reflection in the listener.

Described as a “composer/multi-instrumentalist” by Pitchfork in a review of his first album, Enjoy Your Rabbit, Stevens defies being categorized into a single genre. His music could be described as folk, but it often seems too tech-heavy for that label. As Pitchfork’s review for 2005’s Illinois stated, “He routinely ditches folk’s scrappy, stripped-down aesthetics, but consistently embraces its stories-of-the-people unanimity.” In these reviews and elsewhere, Stevens is lauded for his rich melodies and literary prowess. Stevens isn’t just a great musician, but also an engaging and creative storyteller (he attended the masters program for writing at the New School for Social Research). Fans of Stevens expect lyrics that are as least as beautiful as the songs they’re a part of.

Carrie & Lowell is in many ways a notable departure from the sound of Stevens’ previous album, Age of Adz, and a return to his earlier work. While Age of Adz was noisy and experimental in ways that disappointed some fans (the final track, Impossible Soul, was over 25 minutes long), Carrie & Lowell recalls the delicate, folky sound of Michigan or Seven Swans. However, this new album is incredibly personal in a way that his early albums, which often had a geographical theme, were not. Carrie & Lowell is named for Stevens’ mother and stepfather and focuses entirely on his process of reckoning with his relationship with his often-estranged mother, who passed away in 2012. The album in many ways is a chronicle of Stevens’ mourning process, as he asks questions and expresses desires to a woman who can’t reply.

While many reviewers have touched on the element of faith present in Carrie & Lowell, most have not explored it in depth. However, in my opinion it is impossible to appreciate the album in its entirety without focusing on how Stevens discusses his faith. Stevens is sometimes described as one of the few explicitly Christian artists to achieve secular success, and he does not shy away from talking about his faith and his relationship to God in interviews. Many of his songs, both in his earlier and more contemporary work, contain biblical references or invoke God outright. As a result, many of his songs have references to the Bible or Christian concepts. However, his music is able to transcend its Christian roots and connect to broader and more universal themes of faith, meaning, and loss. In the previously-linked interview, Stevens said of the songs on Carrie & Lowell “At their best, they should act as a testament to an experience that’s universal: Everyone suffers; life is pain; and death is the final punctuation at the end of that sentence, so deal with it. I really think you can manage pain and suffering by living in fullness and being true to yourself and all those seemingly vapid platitudes.”

It is clear from listening to Carrie & Lowell that for Stevens there is a strong connection between examining his relationship with his mother and his faith or belief in God. While most of the lyrics are directed specifically at his mother, Stevens also often invokes a higher power to help him process or deal with his grief. The most explicitly Christian lyric in the album, “Jesus I need you, be near, come shield me”, appears in the song John My Beloved, in which Stevens wrestles with his faith and contemplates his own faults, expressing that “I am a man with a heart that offends/with its lonely and greedy demands”. In No Shade in the Shadow Of The Cross, Stevens bitterly considers his fate in the light of his weaknesses, singing “Drag me to hell” and, in one of the rawest moments on the album, “Fuck me, I’m falling apart”. The title of that song alone implies that he finds little comfort in his religion or belief. Stevens both turns to his faith as a resource to help him mourn but also sometimes finds that it only adds to his emotional confusion.

My favorite song on the new album is Drawn to the Blood. It is far from the most musically complex of the songs on Carrie & Lowell and contains no direct reference to the death of Stevens’ mother, as most of the others do. However, it was at this song that I began literally crying on the PVTA. In just three verses, “For my prayer has always been love/What did I do to deserve this now?/How did this happen?” Stevens poses a fundamental question that religious scholars, clergy, and laypeople have been posing for centuries: why do bad things happen to good people? If someone has generally been faithful, and if their “prayer has always been love”, how could something horrific and life changing, such as the death of an often-distant mother, happen? The listener is left to contemplate this question as the song transforms from a simple melody on the guitar to a soaring soundtrack.

This is, in essence, what makes Carrie & Lowell not only aesthetically pleasing but also incredibly meaningful, both for Stevens and for the listener. The album is able to combine the personal mourning of Stevens with the more universal concept of both struggling with and taking comfort in one’s faith. In my view, this is Stevens’ greatest artistic accomplishment yet. In Should Have Known Better, Stevens sings “Frightened by my feelings/I only wanna be a relief.” For me, this album is not only a relief but a challenge to further explore my own familial relationships and my faith.