Sexual intercourse has forever been a taboo topic in many societies. To this day there is a certain level of discomfort surrounding the human body and what people may or may not choose to do with their bodies. Before the 1970s women had little to no control over their bodies. Abortions were illegal and information about contraception and preventative measures was not discussed or widely distributed. Additionally, contraceptives such as birth control were not easily accessible to the youth or even to married couples. Initially anti-vice reformer and U.S. Postal Inspector Anthony Comstock successfully passed in Connecticut an anti-obscenity bill which included a ban on contraceptives. Comstock campaigned for the enactment of the bill as federal law and was instrumental in twenty-four states adopting their own versions of the Comstock Law. It was not until 1965 that contraceptive devices became more accessible due to the Supreme Court case of Griswold v. Connecticut and it was not until 1972 that all women were able to get prescriptions for the birth control pill or other contraceptive devices, thus controlling their own bodies and their own pregnancy prevention. Despite having more control through availability of contraceptives it was not until 1973 with the passing of Roe v. Wade that women were able to have legal abortions.

Women at Mount Holyoke College were acutely aware of such issues surrounding women’s reproductive health and many were active advocates. Women’s reproductive rights became an area of focus among many women who sought an end to sexual violence, the right to an abortion, and continuing access to contraceptives. To this day women’s reproductive rights are continuously threatened due to strong social stigma as well as social pressures and a lack of access to health care for all.

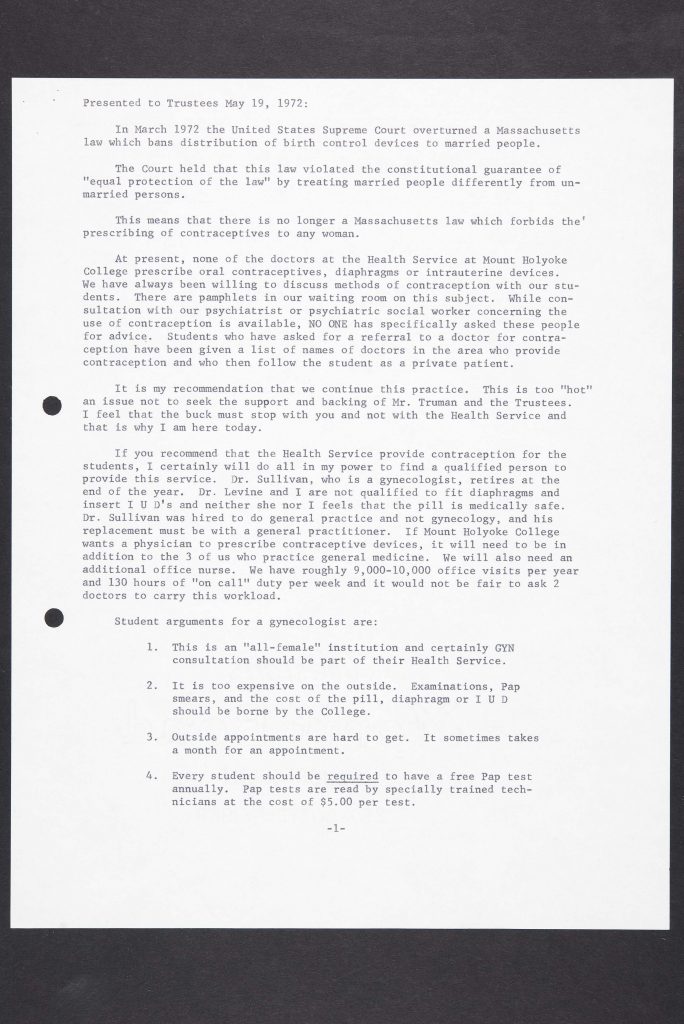

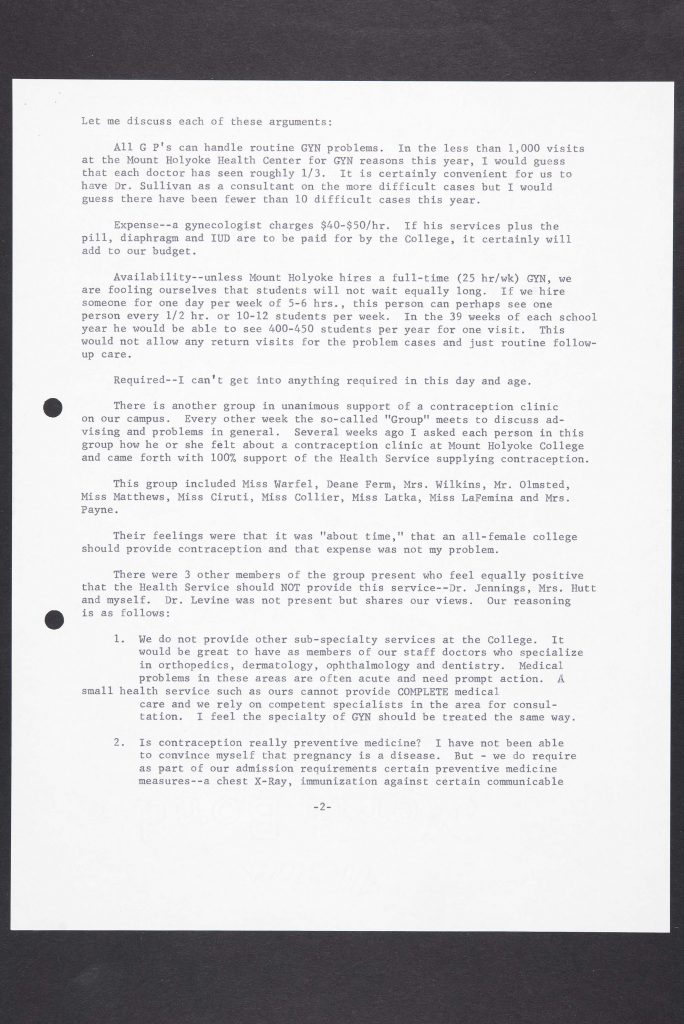

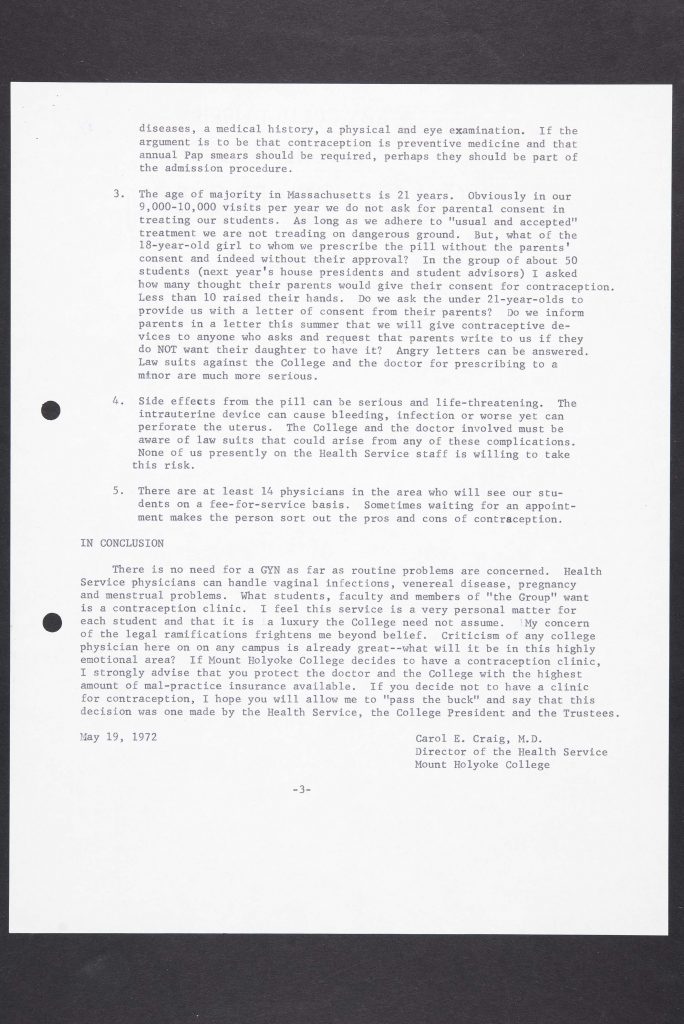

In the above letter presented to the Board of Trustees as well as President Truman, Carol Craig, director of the Health Service, expresses concern about the College providing contraception to the students. Craig advises that it is unnecessary due to cost and risk (relating to potential legal ramifications) to provide a contraception clinic or a gynecologist. Craig in this report requests that if the College should decide not to provide contraception that it be announced to the students as a decision made by the “Health Service, the College President and the Trustees.”

Such a letter demonstrates the unease felt by the College surrounding the distribution of birth control due to potential legal difficulties, parental issues, and future protests that could arise from students unhappy with the decision of the College not to provide contraception clinics. Craig in a later report expresses surprise at the lack of pressure and criticism from students and other womens’ liberation groups.

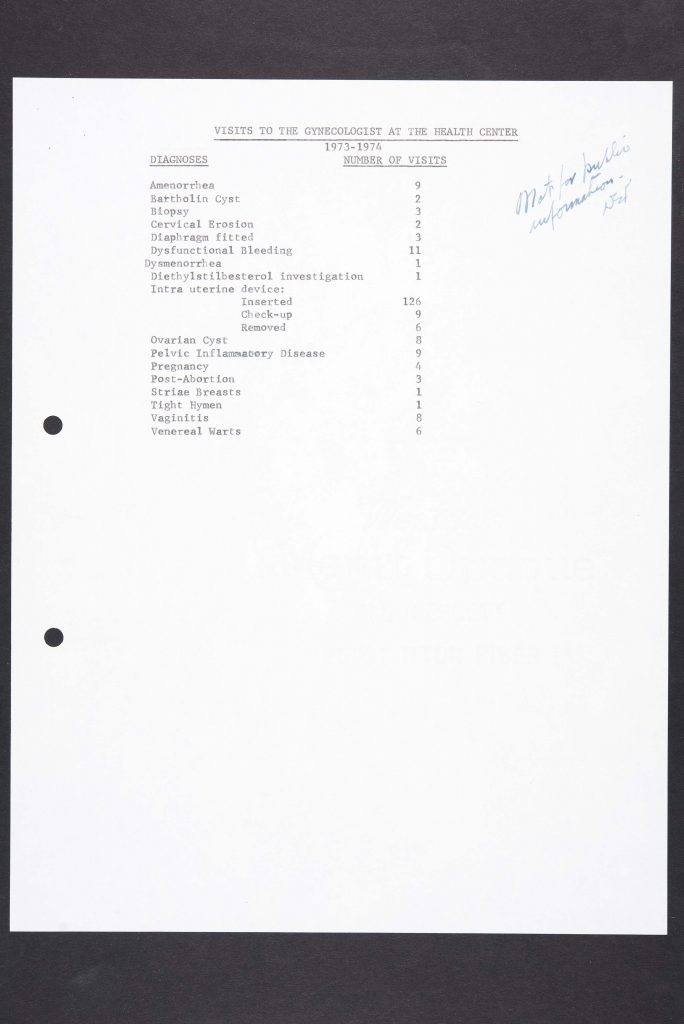

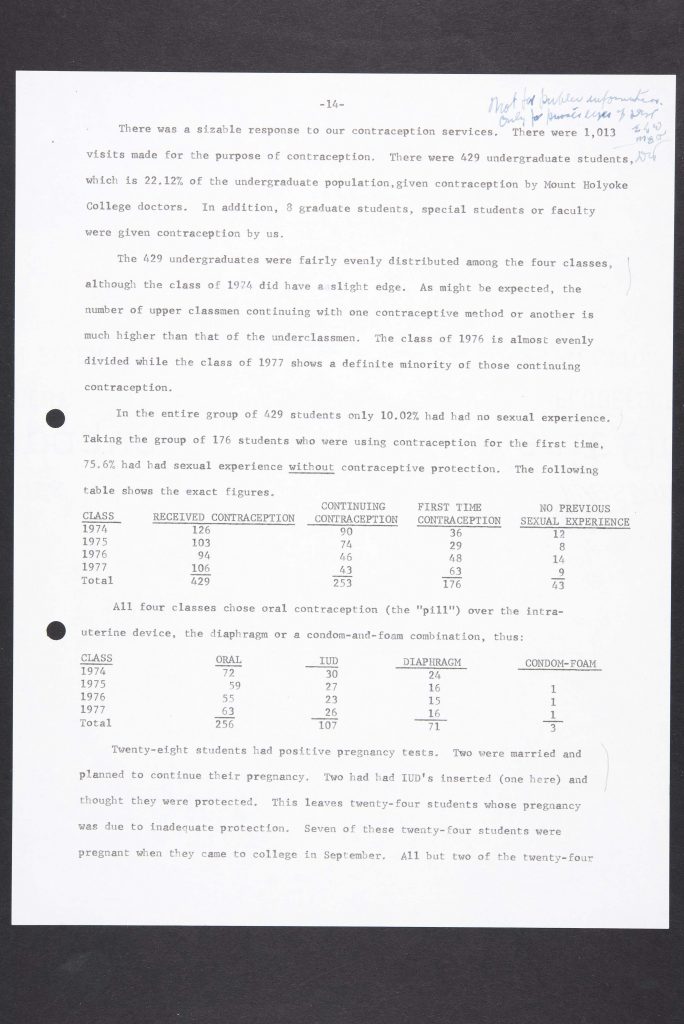

There was worry about providing contraceptive services at Mount Holyoke College. Despite worry it is clear that the services were utilized demonstrated by the following statistics. In this report this is the first year that data on pregnancy was documented and provided in records.

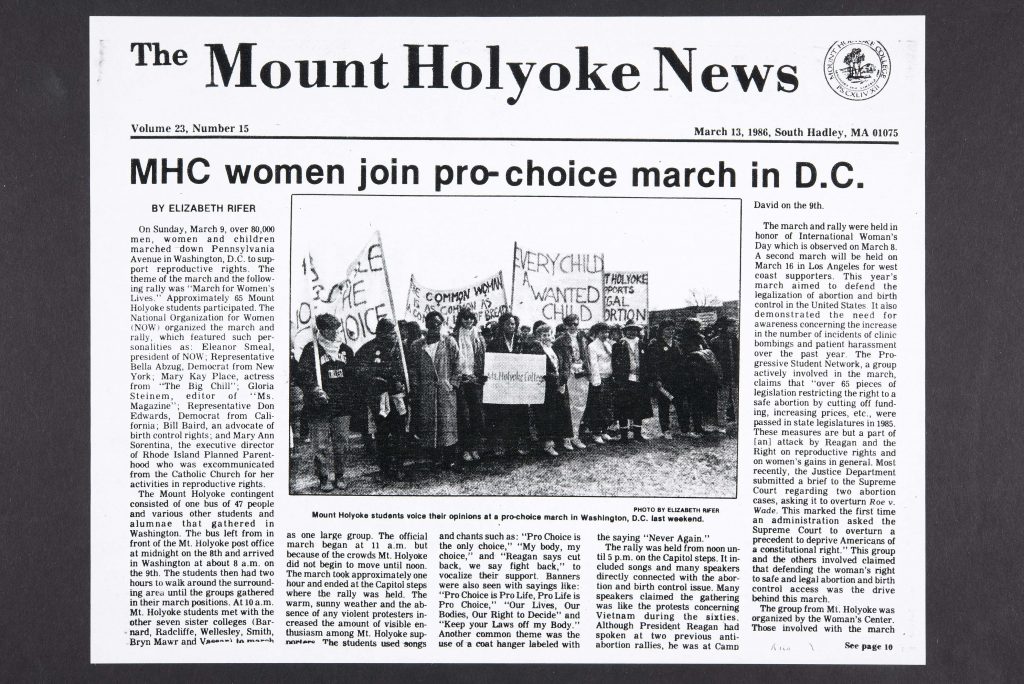

Coat hangers labeled with the saying “Never Again” became a common theme for many marchers and protesters on March 9, 1986. Banners and signs were one of many forms of demonstration. Other methods were chanting as well as using songs to voice opposition.

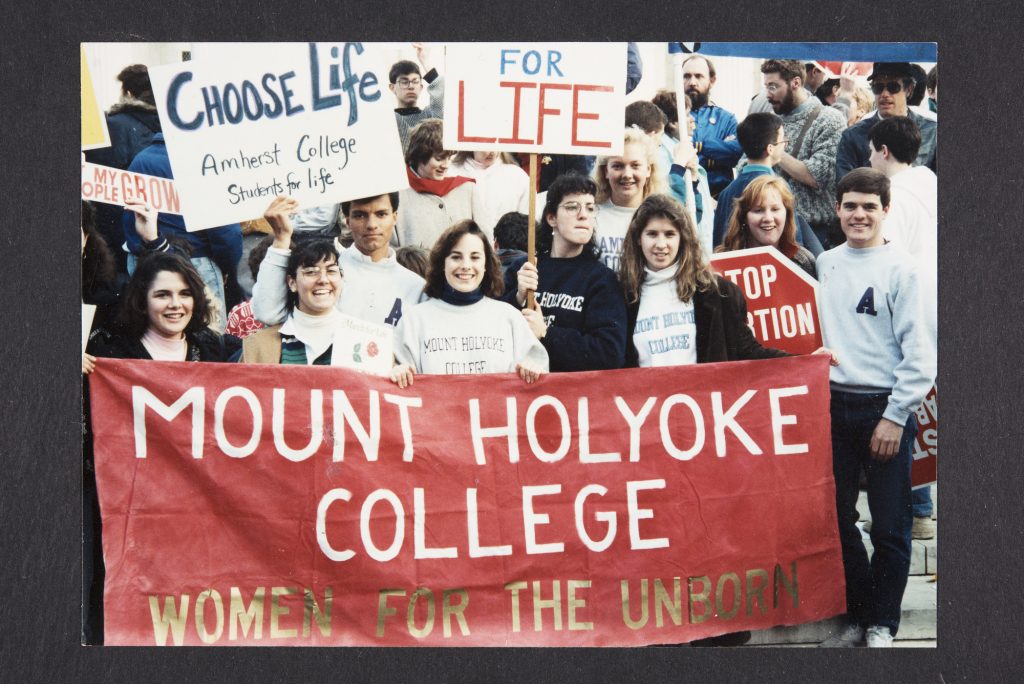

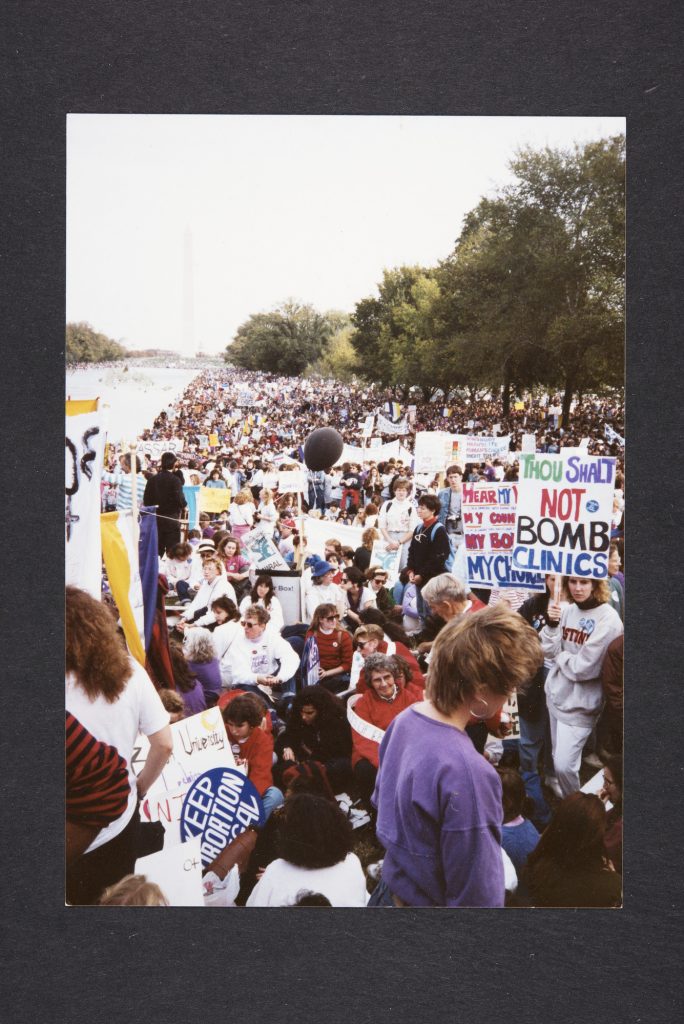

An estimate of about sixty-five Mount Holyoke College students attended the Pro-Choice Rally and the Anti-Abortion Rally in Washington D.C. in 1989 adding their voices to a crowd of 80,000 supporting reproductive rights. Students arrived by bus and private cars to voice their opinions and wave signs and banners to demonstrate their support for the issues.

The above images show Mount Holyoke College students attending both the Pro-Choice Rally and the Anti-Abortion Rally in Washington D.C. in 1989. Protestors of the opposite opinion were present at each.

This portion of the exhibition was curated by Mae Humphreville, 2019.