After the abolishment of domestic work, students could choose to live in co-op dorms where they worked one hour a day and received reduced room and board. Co-op dorms, which lasted from the 1910-1950s, kept more in line with Mary Lyon’s original vision of small family solidarity and lowered expenses. Students waited on tables, answered doorbells, and cared for their rooms, although servants still cooked and did the heavy work. Around 60 students every year were in the several co-op dorms on campus.

Aside from co-ops, the main form of student work after the abolishment of domestic work was waiting tables. This kind of work created concerns about class divide among students. One student, Margaret Chapin from the class of 1925, was a part of a co-op and worked as a waitress her sophomore year. In her letters home, she describes several instances of fellow students “snubbing” her while she was waiting tables.

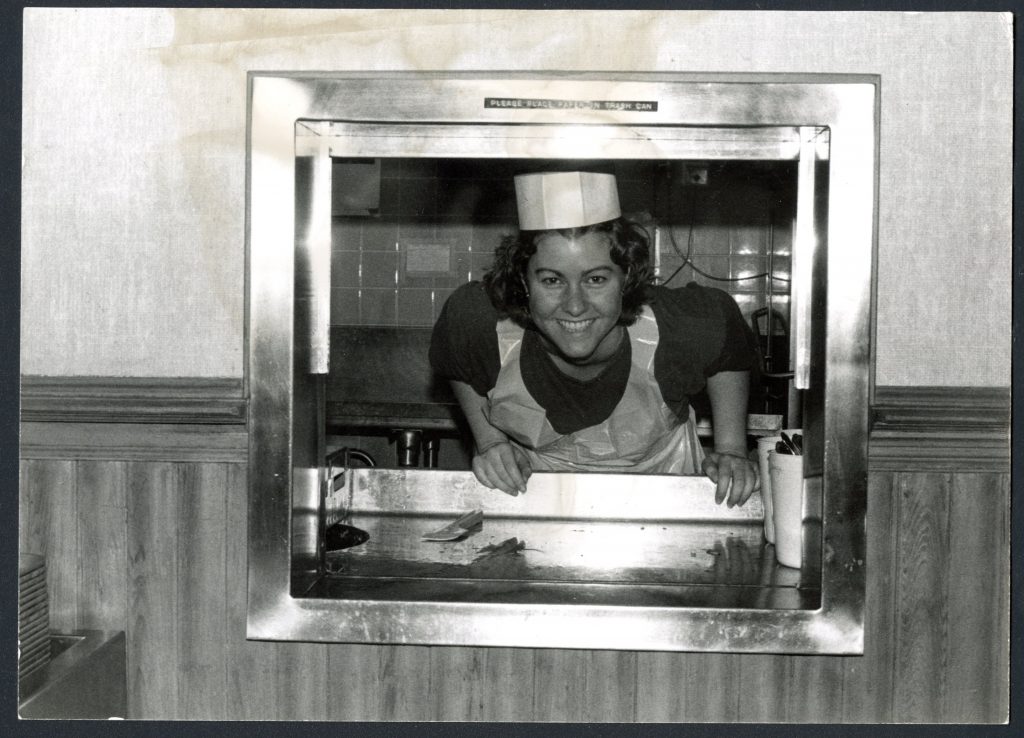

Student work has varied greatly since the abolition of the domestic work system. At various points throughout the 20th century, the College has asked students to donate their time performing domestic work. Still, the importance of domestic work in the affordability of a college education has remained and many students have worked throughout their time here to lower expenses.

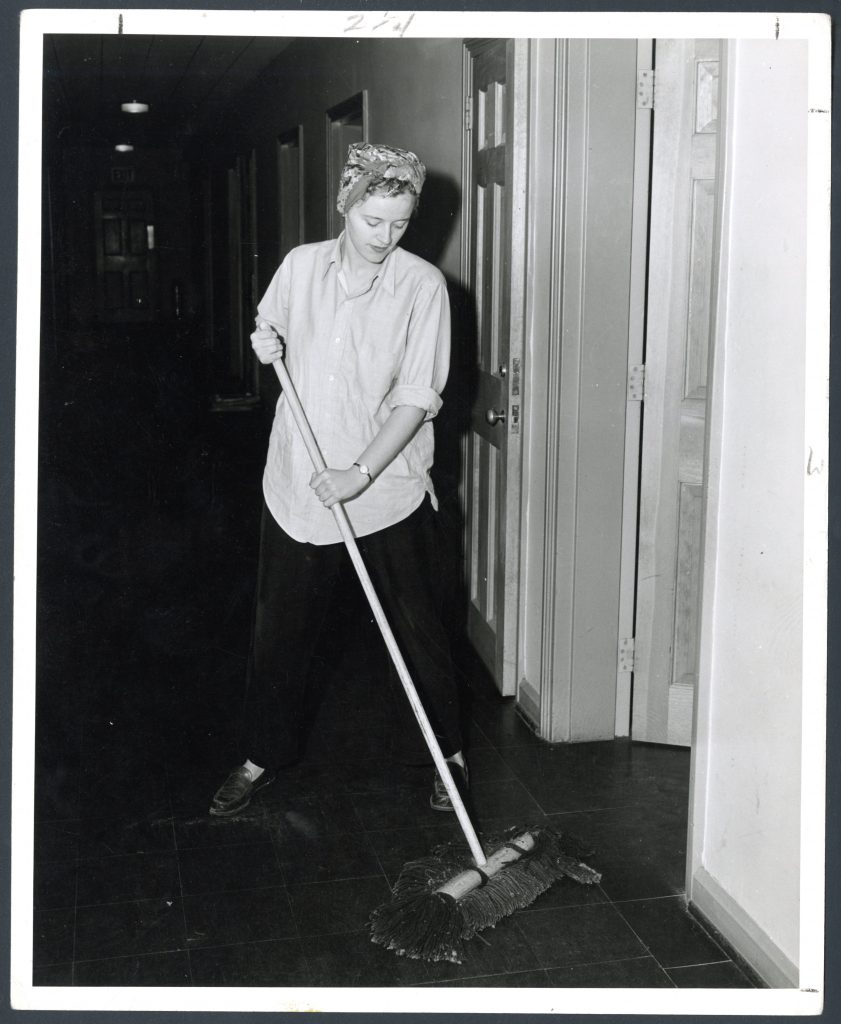

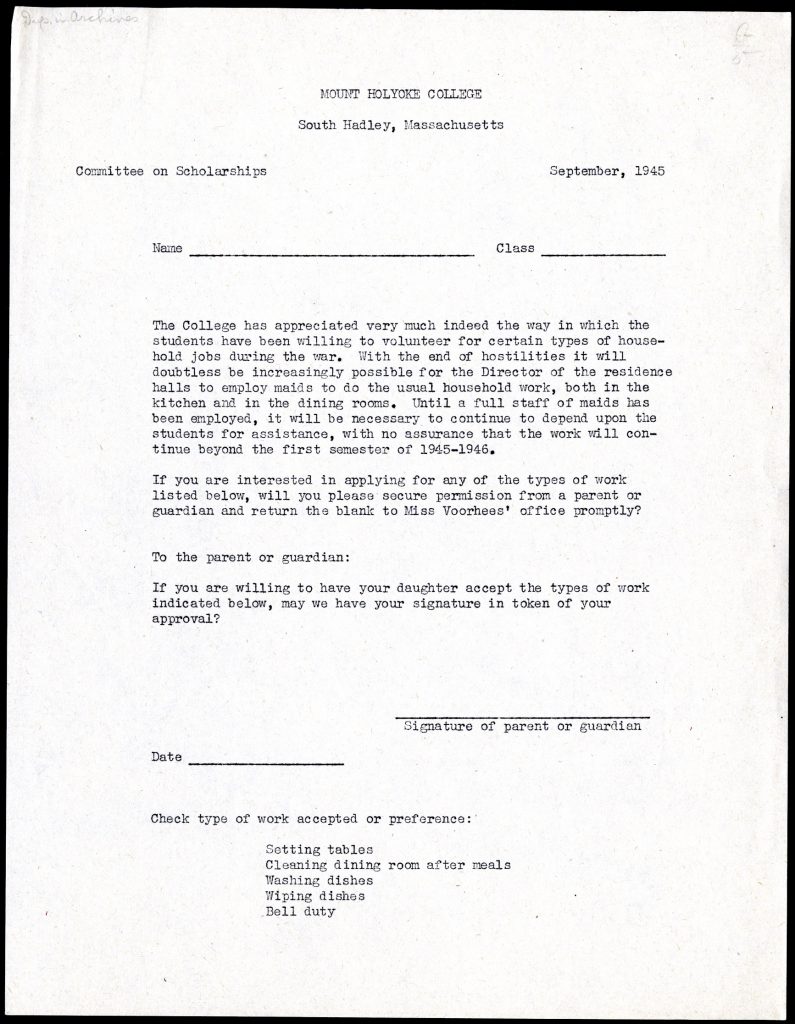

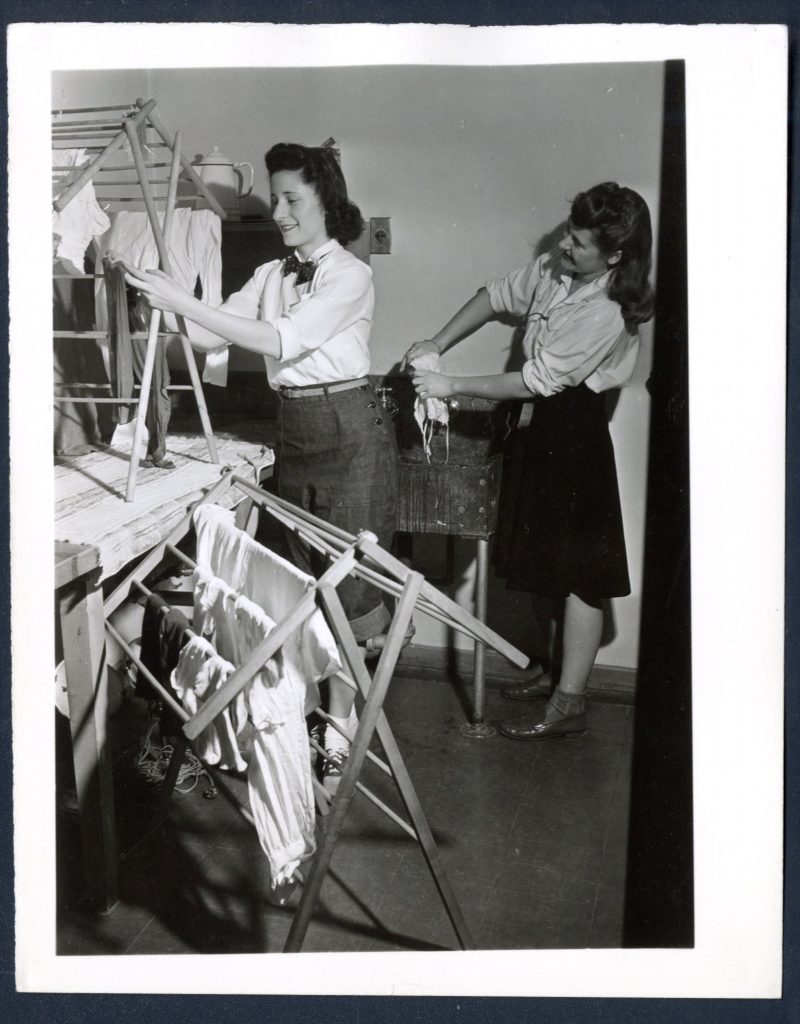

World War II brought changes to student life. In 1942 students had to start sweeping their own rooms. Self-serve breakfast began and the number of maids in each dorm was halved, down to about five in each building to do bell duty, heavy cleaning, cooking, and serving food. Students took on some of the domestic work themselves with permission from their parents.

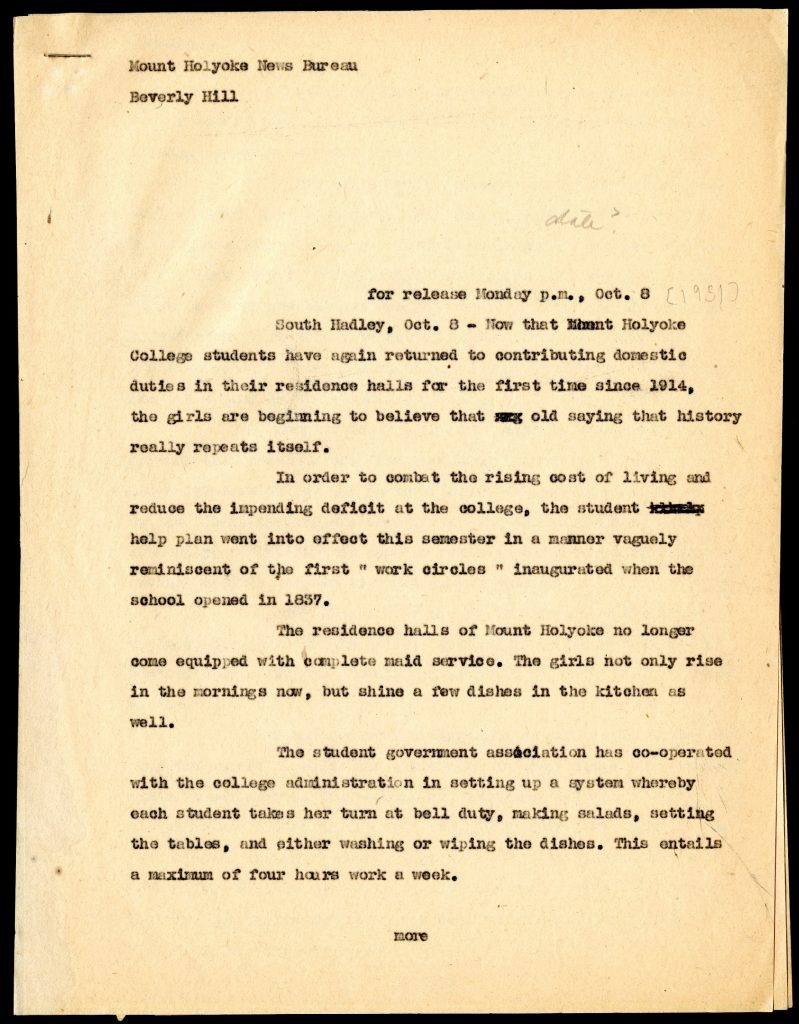

The images below show students performing various domestic work duties throughout the 1940s.

In 1951, to save costs, combat inflation, and the impending deficit, President Roswell Ham asked all students to assist with tasks, no more than four hours a week. Students took jobs answering telephones, doorbells, and drying dishes.

The need for students to volunteer work happened several more times in MHC’s history. For instance, in 1976, federal minimum wage was increased, which would cost the school $130,000 a year, or around $100 a student. Mount Holyoke decided instead to cut the housekeepers’ hours and responsibilities. Then students took up one hour of work a week.

While the College has occasionally asked the student body to contribute their labor, the majority of domestic work since the fall of 1914 has been done by paid staff and students on work study. In the beginning, the student body as a whole worked to keep tuition down for everyone. After the abolition of domestic work, students took that responsibility on individually, working to receive reduced tuition, or a wage to pay for their living expenses.

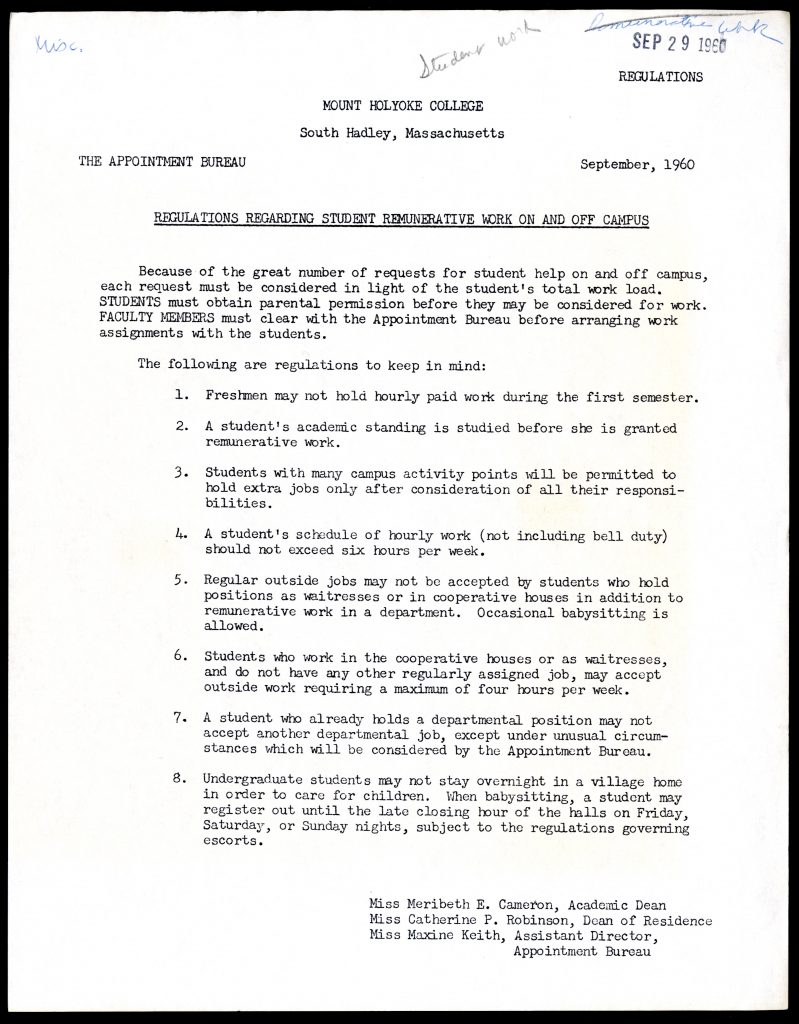

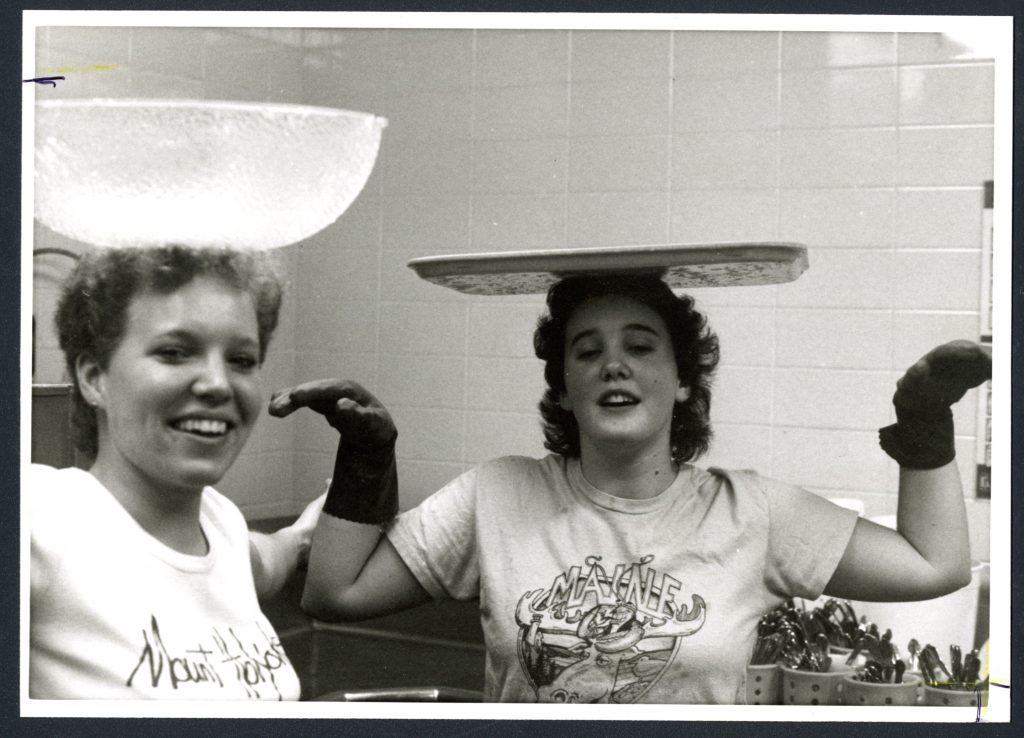

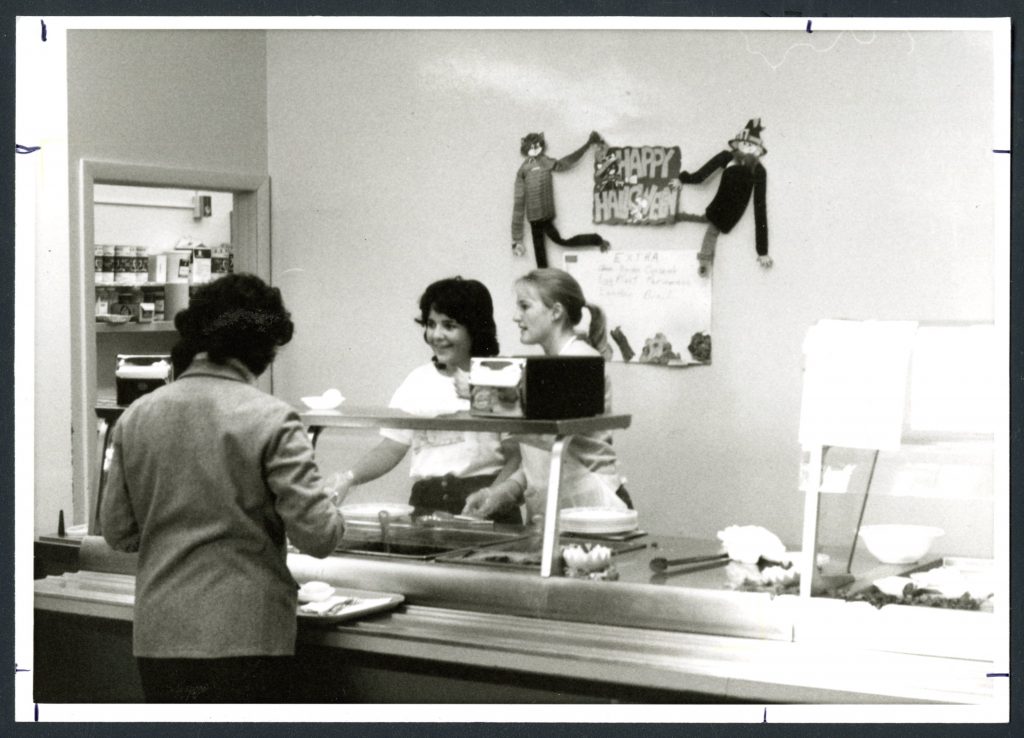

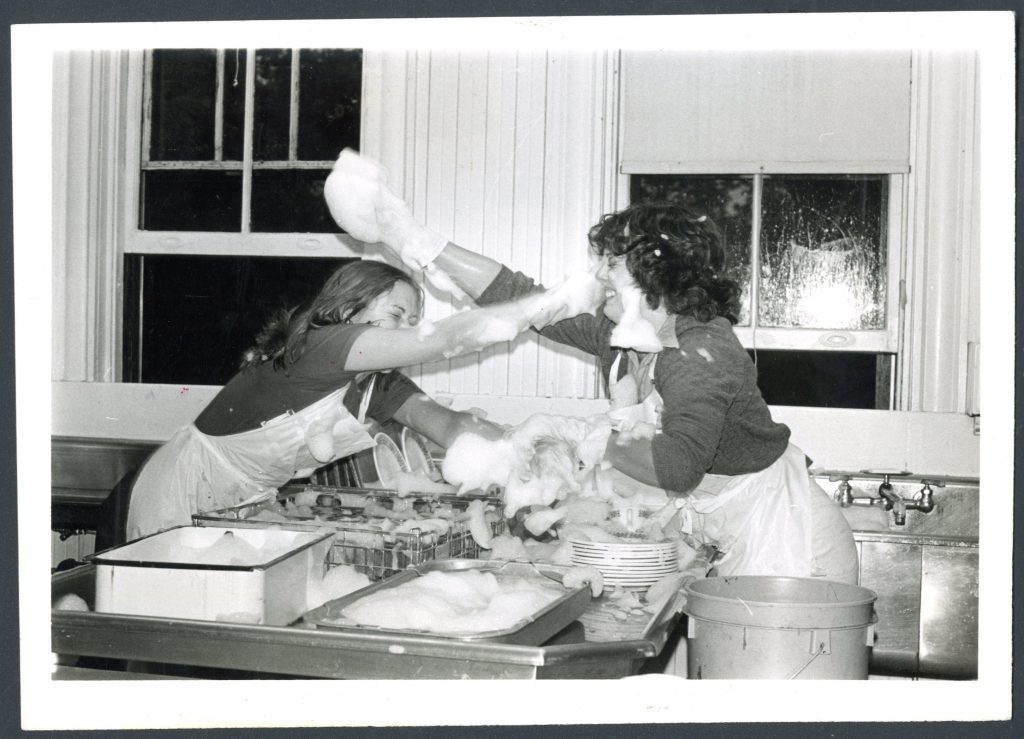

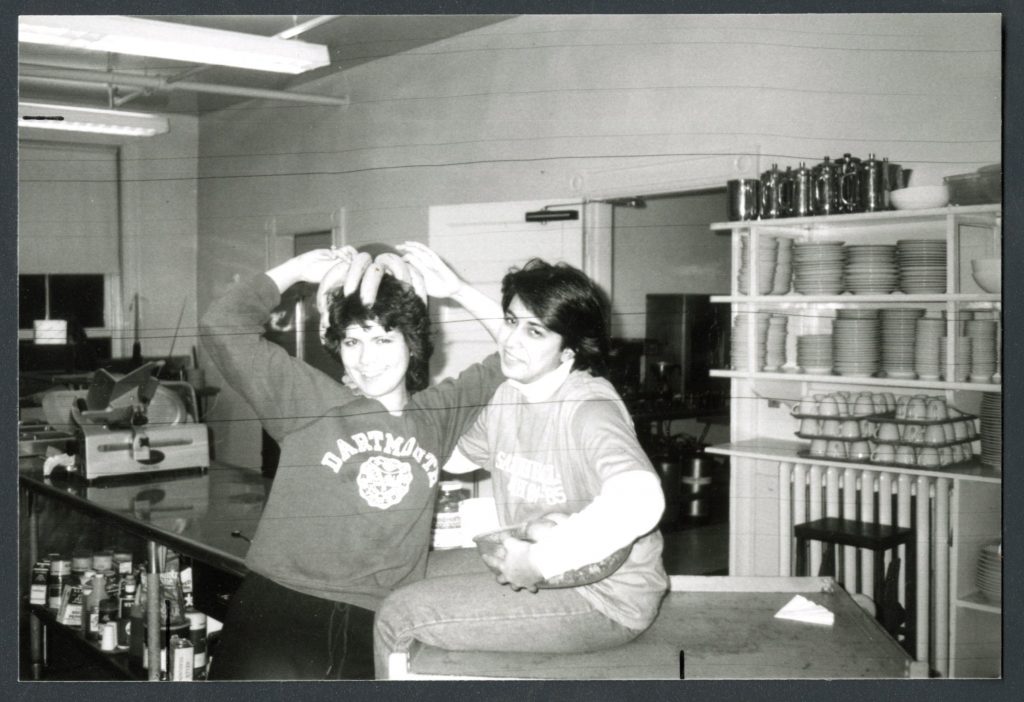

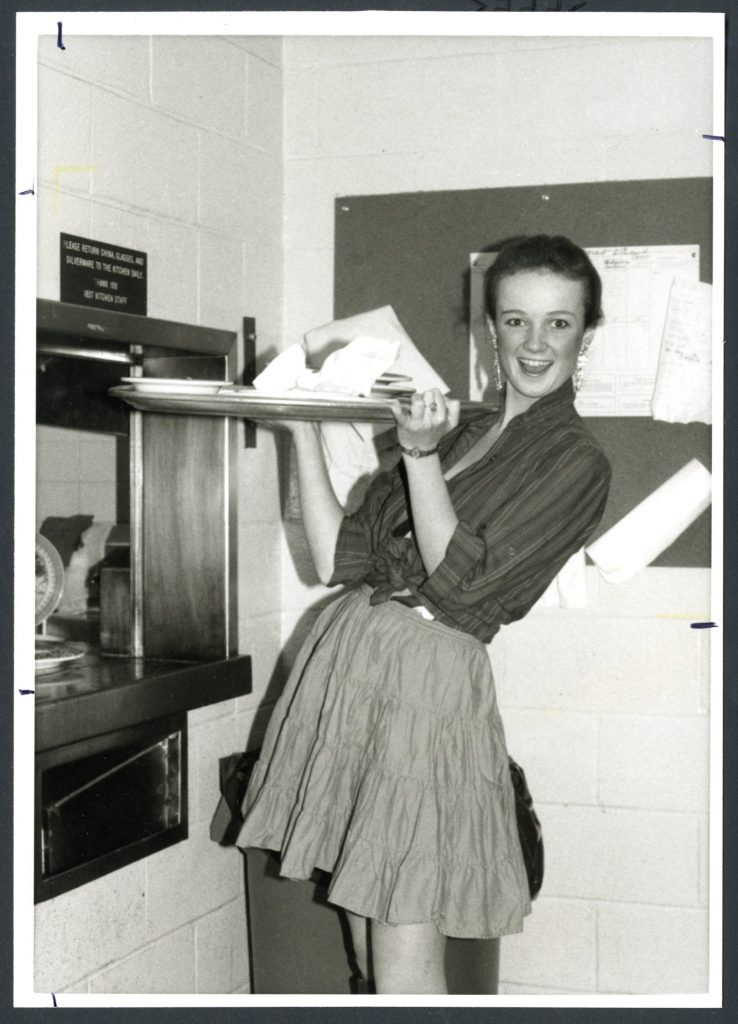

A Mount Holyoke tradition since the 1960s is that First Years work in dining services – a tradition still carried on today. The images below show students working in dining halls throughout the 1980s. Students serving meals continued until 1989.