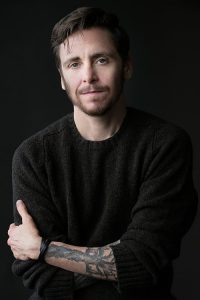

Jordy Rosenberg is a writer, theorist, and professor currently teaching at the University of Massachusetts Amherst in 18th-Century Literature, Gender and Sexuality Studies and Critical Theory.

Rosenberg is a writer deeply invested in literary conversation and collaboration. He has written extensively in several genres from critical theory to speculative historical fiction. He is an editor of several books and special journal issues, including the issue Queer Studies and the Crisis of Capitalism in Gay and Lesbian Quarterly, a project co-edited with Amy Villarejo. This issue featured a cast of canonical queer theory writers to “take the pulse” (127) of queer theory in the modern moment and return its investigations to questions of capitalism, class struggle, racism as an instrument of capital accumulation, and other engagements at the intersection of historical materialism and queer theory. His first book, Critical Enthusiasm: Capital Accumulation and the Transformation of Religious Passion (2011), articulates the history of capitalism as it takes its form in 18th century religious debates with particular attention to space and time.

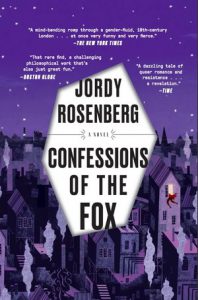

Jordy Rosenberg is not only a powerful voice in theory, but a student (and teacher!) of the critical interventions of science fiction. Rosenberg’s most recent project is a work of speculative historical fiction, Confessions of the Fox, published by Random House in 2018. This novel, for which he received widespread acclaim and a nomination for the Center for Fiction First Novel Prize, explores a trans re-envisioning of the famous 18th century prison break artist Jack Sheppard. Rosenberg describes his attraction to Sheppard through an persistently articulated queer gender presentation in his archival research: “What I’d noticed about that archival material was that it repeatedly presented Jack as very genderqueer—he was generally described as very lithe and effeminate and impossibly sexy. I came to feel that this genderqueer sexiness was a way for writers at the time to conceptualize the appeal of a life lived outside of the regular rhythms of the capitalist workday… I wanted to run with this connection I found in the archives between gender queerness and hatred of/escape from capitalism” (The Millions) This deeply queer and often sexy novel explores what Cam Scott has aptly named an “intergenerational collaboration” between present day Dr. Voth and the historical papers of Jack Sheppard. Rosenberg’s creative and decidedly queer structure of temporal shifting details the parallel and interwoven plotlines of these two trans-historical voices: a trans professor of 18th century literature and queer theory and a notorious 18th century thief, jailbreaker, and lover whom the professor discovers, through reading his lost memoir, is also trans. As Rosenberg often addresses in his public book readings, this work is a speculative imaginary of two flawed and sometimes grating gender-crossing characters. In its heavy reliance on footnotes, Confessions of the Fox slows the process of reading, sometimes forcing a reader to return again and again to the original text. This stylistic option carries a very anti-capitalist logic — not insisting on efficiency but rather a slow and disorderly engagement. Interspersing creative prose with citational reference to present writers and thinkers (ex. Professor Svati Shah’s work, pg. 39), it is clear that Rosenberg’s Marxist investments center in what reads as a justice oriented novel, committed to queerness as a mechanism for capitalist critique.

Jordy Rosenberg is not only a powerful voice in theory, but a student (and teacher!) of the critical interventions of science fiction. Rosenberg’s most recent project is a work of speculative historical fiction, Confessions of the Fox, published by Random House in 2018. This novel, for which he received widespread acclaim and a nomination for the Center for Fiction First Novel Prize, explores a trans re-envisioning of the famous 18th century prison break artist Jack Sheppard. Rosenberg describes his attraction to Sheppard through an persistently articulated queer gender presentation in his archival research: “What I’d noticed about that archival material was that it repeatedly presented Jack as very genderqueer—he was generally described as very lithe and effeminate and impossibly sexy. I came to feel that this genderqueer sexiness was a way for writers at the time to conceptualize the appeal of a life lived outside of the regular rhythms of the capitalist workday… I wanted to run with this connection I found in the archives between gender queerness and hatred of/escape from capitalism” (The Millions) This deeply queer and often sexy novel explores what Cam Scott has aptly named an “intergenerational collaboration” between present day Dr. Voth and the historical papers of Jack Sheppard. Rosenberg’s creative and decidedly queer structure of temporal shifting details the parallel and interwoven plotlines of these two trans-historical voices: a trans professor of 18th century literature and queer theory and a notorious 18th century thief, jailbreaker, and lover whom the professor discovers, through reading his lost memoir, is also trans. As Rosenberg often addresses in his public book readings, this work is a speculative imaginary of two flawed and sometimes grating gender-crossing characters. In its heavy reliance on footnotes, Confessions of the Fox slows the process of reading, sometimes forcing a reader to return again and again to the original text. This stylistic option carries a very anti-capitalist logic — not insisting on efficiency but rather a slow and disorderly engagement. Interspersing creative prose with citational reference to present writers and thinkers (ex. Professor Svati Shah’s work, pg. 39), it is clear that Rosenberg’s Marxist investments center in what reads as a justice oriented novel, committed to queerness as a mechanism for capitalist critique.

Rosenberg is a master of the pithy, clever, thoughtful essay. In “Gender Trouble on Mother’s Day“, Rosenberg writes about his simultaneous experience of coming into his sexuality and approaching feminist philosophy, beautifully blending the healing potential of Butler’s Gender Trouble with a narrative of what he calls a “political mission”: coming out to family. In another reflection on transness and resistance to neo-fascism, Rosenberg’s piece “The Daddy Dialectic” is a “sleazy, schticky, queer” introduction to Marx’s Capital in what he playfully describes as “the voice of my dead mother mediated by testosterone”. These inter-weavings of theory and narrative flow smoothly from Rosenberg. “…This essay is not exactly about family history,” he writes, “It’s not exactly about Frankfurt School Marxism either, and it’s not exactly about fascism. Rather, it’s about how for some of us, these concerns can’t be kept apart.” From Rosenberg’s impressive literary skillset have also emerged contemplations of Mad Max on the figure of the War Boy and testosterone and “found/faux footage” lecture notes in a critique of surface reading within the literary Humanities.

Rosenberg crafts a space for those of us who float precariously between creative writing and political theorizing. Jordy’s work is a profoundly comforting entrance for we who have no interest in keeping — or more accurately, producing — the theoretical and the flesh and blood as separate.