Subjects and Themes

Bacchic celebrations were a different kind of paradise than that portrayed by sea sarcophagi. The Bacchic celebrations depict high-energy scenes of followers of the Roman god Bacchus partaking in the pleasures of drinking and dancing. Bacchus was a relatable and popular god. People liked to think that by worshiping the god of pleasure they would be gifted with joy and ecstasy. His followers, the thiasos, consisted of satyrs young and old, sons of Silenus, old Silenus, maenads, fauns, centaurs, and a variety of exotic animals. Bacchus could make the old just as happy as the young. Scenes of the thiasos and Bacchus celebrating, feasting, and dancing, were among the most popular subjects of Roman sarcophagus reliefs (Figure 12). [1] These scenes depicted the enjoyments and celebrations of life. Though there was a savageness to the Bacchic cult, there are few threatening images found on the sarcophagi. Though there are often moments from myths relating to Bacchus depicted, often the main subject is actually the excitement of the thiasos.

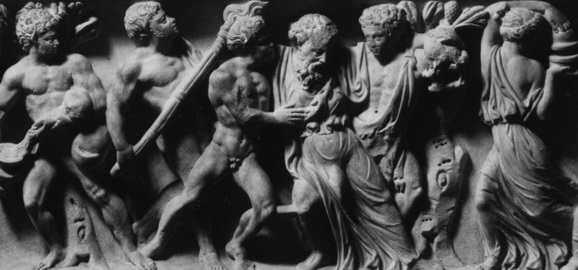

There were several different ways that the thiasos were depicted. For the most part, the satyrs and the maenads made music and danced (Figure 16, Detail B). The shrill and frenzied sounds coming from these musical instruments contrasts the calm choir of the ocean – giving a viewer a different kind of bliss. The maenads usually played the symbols and drums while the satyrs played the double flute or panpipes. The centaurs and sons of Silenus did not dance and are seen playing primarily stringed instruments. The music brought these beings into a frenzy. The dancing and movements among the thiasos varied. The maenads would turn and bend their bodies along with the wild music, while the satyrs showed their strength by jumping and stamping.

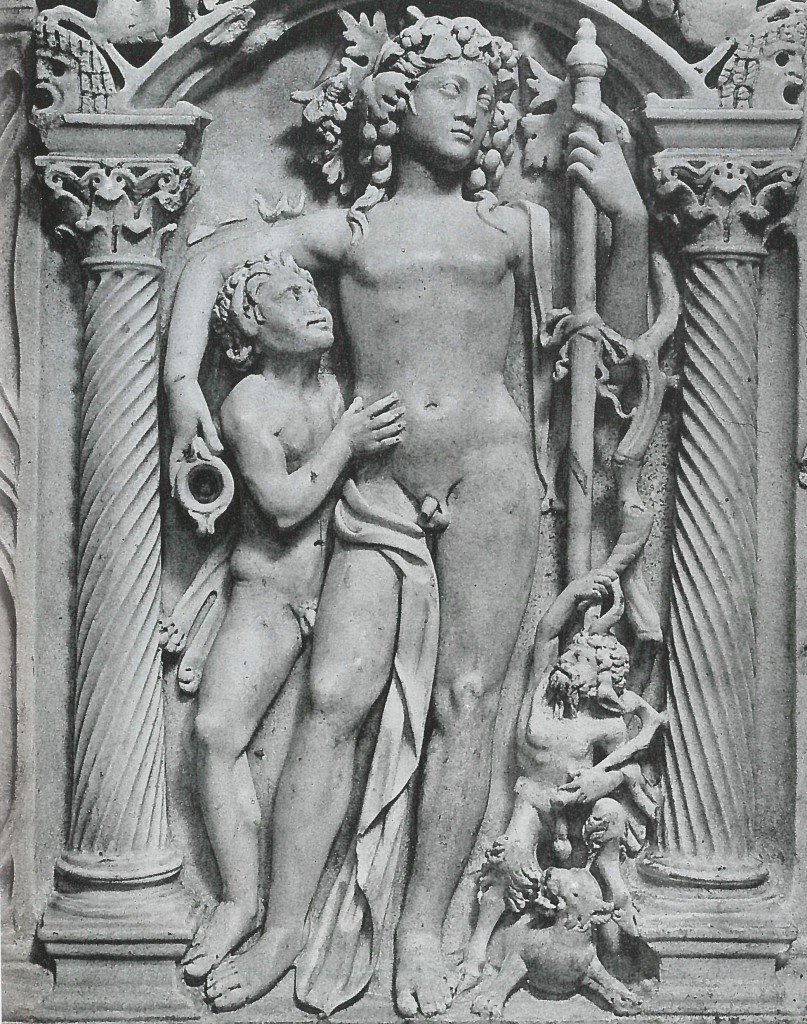

Bacchus himself and old Silenus represent the two types of states brought on by drunkenness (Figure 13). Bacchus is often relaxed among the chaos around him and looks off into the distance. Silenus is a more stereotypic drunk, constantly falling over and needing support to stay upright. Both are just as happy and neither state is considered better or worse. Drunkenness is a constant theme no matter what else is shown in these types of sarcophagi.[2] Scenes of general revelry for Bacchus, with no mythological context, are also popular. Bacchus is not always depicted but the celebration of him always is.[3]

By having this type of imagery on a sarcophagus, the living could imagine that their loved were eternally celebrating the pleasures of life with the divine. The sorrows and grief of the living could be forgotten for at least a moment as they viewed these happy scenes. In contrast to the sea sarcophagi, there were some examples of these Bacchic celebrations placed into the context of a specific myth.

Examples

The “Childhood Sarcophagus” from circa 150—160 AD was a smaller size than other marble sarcophagi, suggesting it was for an adolescent (Figure 14). It is currently on display at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore. The sarcophagus depicts a young Bacchus being nursed by a nymph and an old Silenus (Figure 14, Detail A). In the lower left of the composition a nurse prepares a bath for a small panther cub, one of the god’s favorite animals.

Satyrs carry wine, hold up drunken characters, carry torches, and prepare a mixing bowl for the wine (Figure 14, Detail B). Maenads dance and twirl on the right end of the sarcophagus playing the cymbals.[4] The young person that this sarcophagus could have held was being compared to the young god, also the son of a mortal woman. The composition on this sarcophagus would prompt viewers to think of their loved on as eternally youthful and celebrating the joys of life among the thiasos while also being cared for by the nurses of this world. All of these figures are here to celebrate the birth of the god, and allude to the eternal celebration of the deceased youth. The lid of the sarcophagus depicts satyrs and maenads at a banquet, following through with the thiasos connection.[5]

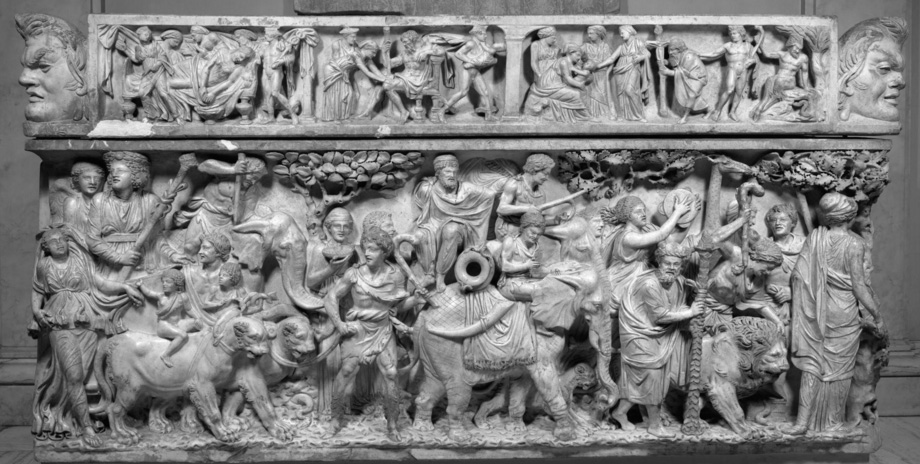

Another popular myth referenced on these sarcophagi was Bacchus’ triumph of India. The “Sarcophagus with the Triumph of Dionysus” from circa 190 AD was found on the Via Salaria in Rome and is currently on display in the Walters Art Museum (Figure 15). These types of images were literal. In addition to obviously celebrating the joys of life, for which the thiasos were known, the real triumph here is the triumph of the deceased over death. Such a scene of victory would evoke this train of thought.

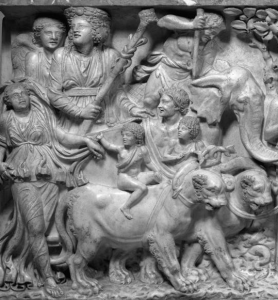

Bacchus, on the left, rides in a chariot being pulled by two panthers (Figure 15, Detail B). Before him, as in other Bacchic sarcophagi, is a procession of the thiasos, and exotic animals. On the lid, the birth of Bacchus, discussed previously, is depicted once again. Old satyrs jump around and stomp their feet while maenads spin and dance around playing the drums (Figure 15, Detail A). The liveliness of a Bacchic scene is certainly not lost here.[6]

Some of these types of sarcophagi did not have any kind of mythological context and showed only acts of general celebration (Figure 16). This sarcophagus from circa 160-170 AD is currently at the Palazzo dei Conservatori in Rome. It depicts a tightly packed thiasos celebration with exotic animals, satyrs, maenads, and centaurs. A pair of centaurs pull the chariot of a drunk Bacchus (Figure 16, Detail A). Bacchus is identified by his thyrsus. On the lid of this sarcophagus is Ariadne reclining between a satyr, Pan, and Silenus.

Another type of blissful imagery used on Roman sarcophagi is peaceful sleep. In addition to the myth of Endymion and Selene, Ariadne and Bacchus were also a popular choice (Figure 19, Detail A). The two myths were even seen as pendants of each other. Because of the association with Bacchus, sometimes these scenes of a sleeping Ariadne are surrounded by noisy thiasos. Even though a large part of the composition is made up of these drunken creatures, I believe the main focus and message those sarcophagi are trying to point out to the viewer is Ariadne’s dream filled slumber and her love of Bacchus. To read more about the sarcophagi showing Bacchus and Ariadne, see the pages under Sweet Dreams.

[1] Paul Zanker and Bjon Ewald, Living with Myths: The Imagery of Roman Sarcophagi, trans. Julia Slater (Oxford University Press, 2012), 130-131

[2] Ibid., 133-134

[3] Karl Lehmann-Hartleben and Erling Olsen, Dionysiac Sarcophagi in Baltimore (Baltimore: Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, 1942), 16

[4] Ibid., 11

[5] “Sarcophagus Depicting the Birth of Dionysus.” The Walters Art Museum. Accessed November 30, 2015. http://art.thewalters.org/detail/16574/sarcophagus-depicting-the-birth-of-dionysus/

[6] “Sarcophagus with the Triumph of Dionysus.” The Walters Art Museum. Accessed November 30, 2015. http://art.thewalters.org/detail/33305/sarcophagus-with-the-triumph-of-dionysus/