The Myth

The myth of Bacchus and Ariadne begins with the Greek hero Theseus. The Athenian hero Theseus, snuck onto the island of Crete in order to slay the vicious Minotaur. With the help of the princess Ariadne, Theseus successfully defeats the beast. He falls in love with Ariadne, but only for a short time. As they escape Crete, Theseus and Ariadne stop to rest on the island of Naxos. While Ariadne sleeps, Theseus sails away, abandoning her on the deserted island. While Ariadne rests the god of wine, Bacchus, comes upon her and instantly falls in love. Ariadne eventually becomes his immortal wife.

“After he [Minos] conquered the Athenians their revenues became his; he decreed, moreover that each year they should send seven of their children as food for the Minotaur. After Theseus had come from Troezene, and had learned what a calamity afflicted the state, of his own accord he promised to go against the Minotaur . . .

When Theseus came to Crete, Ariadne, Minos’ daughter, loved him so much that she betrayed her brother and saved the stranger, or she showed Theseus the way out of the Labyrinth. When Theseus had entered and killed the Minotaur, by Ariadne’s advise he got out by unwinding the thread. Ariadne, because she had been loyal to him, he took away, intending to marry her.

Theseus, detained by a storm on the island of Dia [Naxos], though it would be a reproach to him hif he brought Ariadne to Athens, and so he left her asleep on the island. Liber [Dionysos], falling in love with her, took her from there as his wife.”

– Pseudo-Hyginus, Fabulae 40 – 43

Themes and Motifs

The coming of Bacchus onto the island of Naxos approaching a sleeping Ariadne symbolizes the crossing of the divine (the living) and the mortal (the dead) or the passage of the dead to a better life. The representation of this myth on a sarcophagus could allude to the death of a woman receiving redemption after life at the hands of her savior, a god.[1] The sleeping Ariadne and the fixated Bacchus could also evoke the notion of separated lovers. The eventual marriage of the two could also refer to an eventual happy reunion and eternal love of a husband and wife in the afterlife.[2] A portrait of the deceased was commonly used as the face of Ariadne. This directly linked the deceased to the blissfully sleeping mortal woman while also alluding to her earthly beauty. As with the Selene and Endymion sarcophagi, sleep closely relates to death in this context.

Though many artists depict this moment of abandonment as tragic, the Bacchus and sleeping Ariadne sarcophagi that came from Roman workshops show Bacchic joy and happiness. This theme on a sarcophagus gives the message that the two lovers were happy during their lives and they lived life to the fullest. By showing this exact moment, the sarcophagus evokes the idea of letting the deceased, as she sleeps now, dream of these pleasures eternally while her beloved approaches her, looking on with a loving gaze. There is an everlasting love and yet a never-ending longing of the two lovers to be reunited one day to forever partake in the celebrations of life.[3] In a way, resurrection is the same as Ariadne awakening. Because sleep is temporary, she has the ability to wake up and live forever in her dreams. For now though, the deceased sleeps, dreaming of a pleasurable and divine world. To the Romans this myth meant that there was still hope of salvation for their “sleeping” loved ones.

Examples

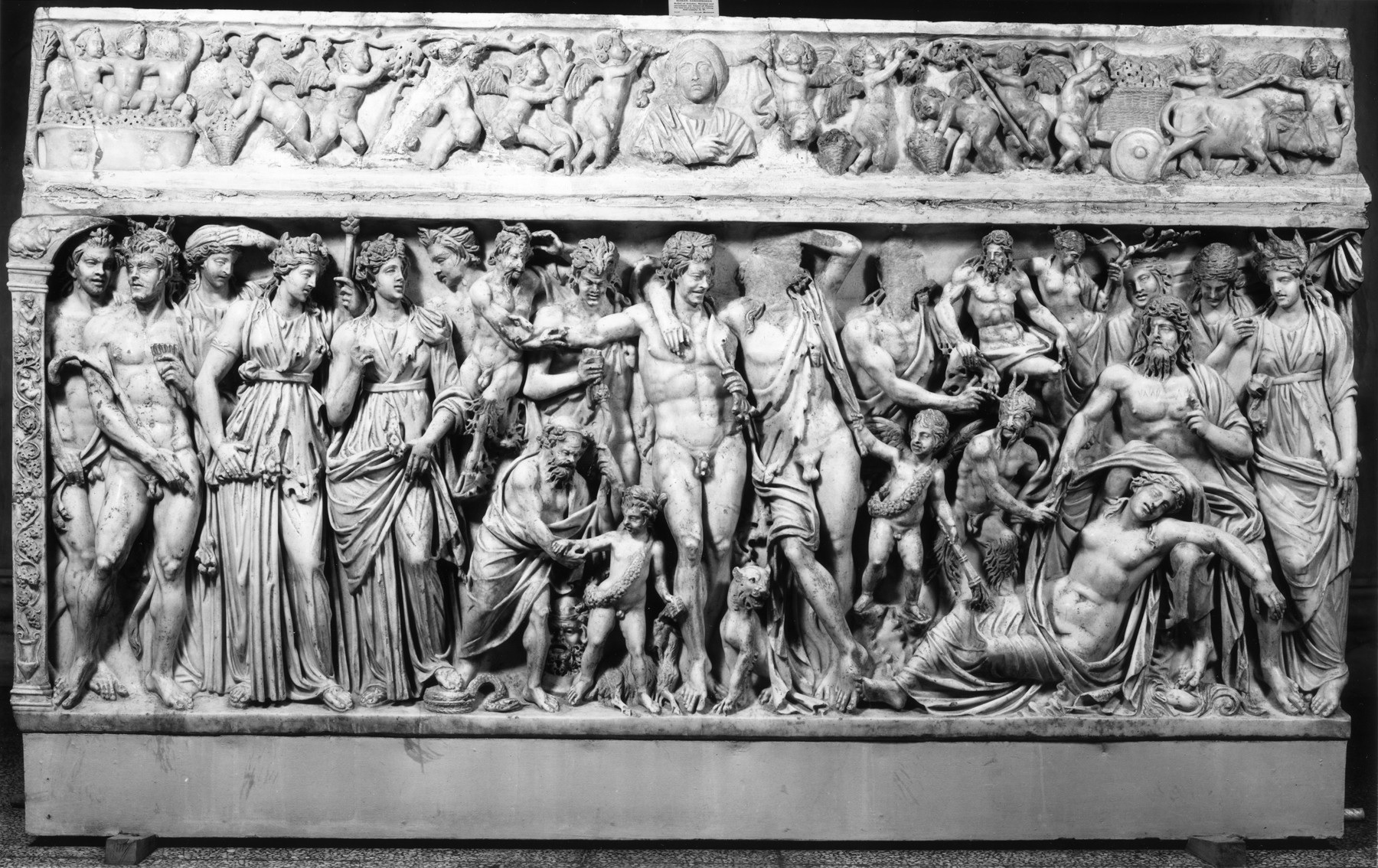

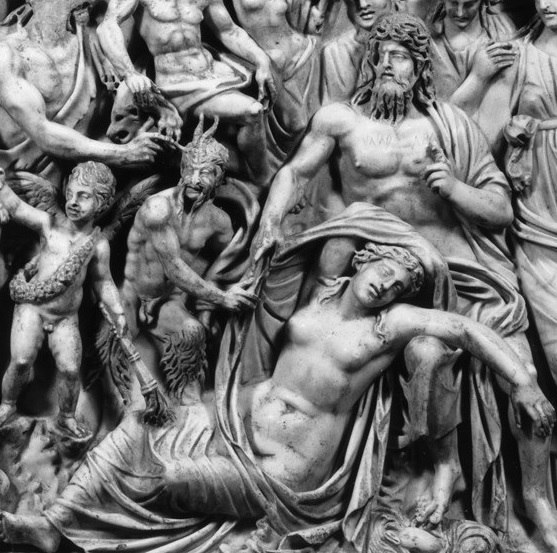

This sarcophagus of Bacchus approaching Ariadne dates from circa 190—200 AD and is currently on display at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore (Figure 17). The artists makes the approach of Bacchus to Ariadne busy with the inclusion of several maenads and satyrs throughout the scene. Ariadne rests her head in the lap of Thanatos, the god of death (Figure 17, Detail A).

This brings the viewer to the literal conclusion that her sleep equates to death. Eros brings the god toward the sleeping maiden’s direction. Several satyrs pull away Ariadne’s clothing to reveal her naked body. This is a similar gesture found in some Selene and Endymion sarcophagi. The viewer is meant to be also enamored by her naked body as Bacchus was. More literally than other sarcophagi, Bacchus is able to bring Ariadne out of the hands of death and into divine celebration. [4]

This sarcophagus from circa 130—150 AD, currently on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, is the most rooted in myth of all the other sarcophagi (Figure 18). Rather than the single moment of Bacchus coming upon Ariadne being the focus, two other moments from the myth of Theseus and the Minotaur are depicted.

This example of a cyclic compositions shows the moment when Ariadne first gives Theseus the thread to find his way through the labyrinth (Figure 18, Detail A), the scene just as Theseus slays the monster (Figure 18, Detail B), and when Ariadne is abandoned on Naxos (Figure 18, Detail C).

Each scene is beautifully separated by draped garlands held up by large Erotes. Unlike the other examples of Ariadne and Bacchus, Bacchus has not appeared yet. Theseus is still in the midst of abandoning the woman on Naxos. She sleeps below what appears to be some sort of fruit bearing tree which may allude to the events to follow. Erotes playing about line the lid.

Though Bacchus does not appear, the sleeping figure, Ariadne, is still present and the allusions that come along with sleep still apply. She is evening in the same reclining position as the other sarcophagi. Those who viewed this sarcophagus would see this and think of the salvation that is still possible for their loved one.

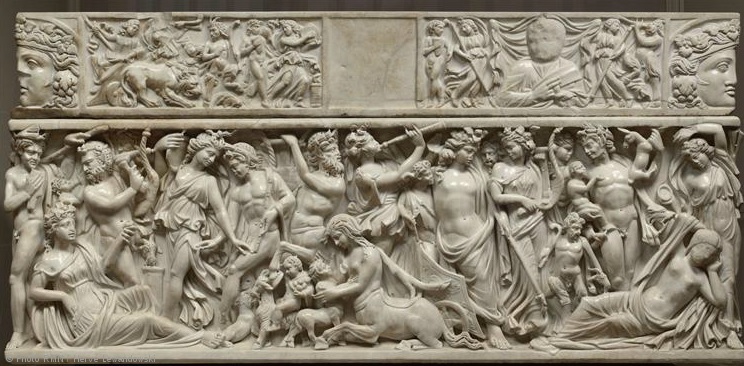

This sarcophagus from circa 235 AD most likely originated from a workshop in Rome and is currently on display at the Louvre (Figure 19). The composition of this sarcophagus is compact and lively. Bacchus appears still among his dancing and celebrating companions as he looks on at Ariadne. The face of the mortal is blank suggesting that the portrait of the deceased would have been placed there (Figure 19, Detail A).

The artist attempted to calm the chaos by grouping each of the figures by twos and threes. Ariadne’s position on the right is balanced out by a reclining maenad on the opposite side of the scene. There is a real sense of joy and merriment in this composition, much like the Bacchic celebrations of other sarcophagi. Unlike those sarcophagi, the message of sleep and the specific myth screams louder than the noisy thiasos. The hope for a divine savior, the thought that she may be dreaming of such divine parties, and the eventual reunion with a beloved were the primary messages in addition to a celebration of life’s pleasures.[5]

[1] Paul Zanker, “Reading images without texts on Roman sarcophagi,” Res 61/62 (2012), 173-174

[2] Karl Lehmann-Hartleben and Erling Olsen, Dionysiac Sarcophagi in Baltimore (Baltimore: Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, 1942), 39-40

[3] Paul Zanker, “Reading images without texts on Roman sarcophagi,” Res 61/62 (2012), 176

[4] “Sarcophagus with Dionysus and Ariadne.” The Walters Art Museum. Accessed December 1, 2015. http://art.thewalters.org/detail/23618/sarcophagus-with-dionysus-and-ariadne/

[5] Paul Zanker and Bjon Ewald, Living with Myths: The Imagery of Roman Sarcophagi, trans. Julia Slater (Oxford University Press, 2012), 132