Reading Material of the Week: “Introduction to Melanie Klein” – Juliet Mitchell, in Reading Melanie Klein, edited by Lyndsey Stonebridge and John Phillips; “Infantile Anxiety Situations Reflected in a Work of Art and in the Creative Impulse” – Melanie Klein; “The Importance of Symbol Formation in the Development of the Ego” – Melanie Klein. I also went back and read The Malady of Death by Margurite Duras.

____________________________________________

Melanie Klein’s writings illustrate her experiential studies of the child, going through her interactions in great detail. For Klein, violence centers her exploration of the infant and the child’s ego. She talks about the child’s anxiety and guilt related to the penis and the mother’s body. One could say that the idea of the penis destroying the female body via penetration is her primary thesis point, specifically focusing on translating the Freudian psychoanalytic stages of child development and taking the Oedipus complex for granted. This is an interesting concept, the idea that the male actually destroys the female body, hurts it violently, in the act of hopeful reproduction. In many ways, it is a very feminist reading of the child’s psychosexual development; the language Klein uses, as well as her almost hyper-insistent return to (or repetition of) “the zenith of sadism” being reached, the anxiety (according to Freud’s interpretation) about that sadism [throughout her diagnosis in “Symbol Formation in Ego Development”], gives the Oedipus complex and its manifestations a new tone. In “The Importance of Symbol Formation,” Klein talks about her engagement with a small boy named Dick, who does not display the Oedipus complex normally (she concludes that the boy represents an instance of childhood schizophrenia, though today he would be considered autistic). Klein manages to find references to the mother and father in everything the small child does (which seems mildly pedantic to me), and that in many ways this hyper-focus results in a biased assessment of the child’s ego. Let me supply a section where this is most salient:

The first time Dick came to me, as I said before, he manifested no sort of affect when his nurse handed him over to me. When I showed him the toys I had put ready, he looked at them without the faintest interest. I took a big train and put it beside a smaller one and called them ‘Daddy-train’ and ‘Dick-train’. Thereupon her picked up the train I called ‘Dick’ and made it roll to the window and said ‘Station’. I explained: ‘The station is mummy; Dick is going into mummy.’ He left the train, ran into the space between the outer and inner doors of the room, shut himself in, saying ‘dark’ and ran out again directly. He went through this performance several times. I explained to him: ‘It is dark inside mummy. Dick is inside dark mummy.’ Meantime he picked up the train again, but soon ran back into the space between the doors. While I was saying that he was going into dark mummy, he said twice in a questioning way: ‘Nurse?’ (102)

To our adult minds it does indeed seem as though Dick shows that the child’s position is at least with the mother, (Klein interprets this as importantly inside her, as in, inside/entering the womb). When Klein explains to the child that the train station is the mother and the child responds by going inside the closet, it seems as though Klein has implanted the idea in the child’s head. Her language betrays this, her phraseology “going into mummy” suggests already to the child that he has gone into something, thus requiring an appropriate response to the idea of ‘going into’ and of therefore ‘being inside’. Further, Klein’s claim that when Dick “discover[s] the wash-basin as symbolizing the mother’s body, and displayed an extraordinary dread of being wetted with water,” that “urine represented to him injurious and dangerous substances” (104). It seems to me that the child has rather equated water and basin-shapes with the mother, and thus considers that anything that should go inside the basin-shape already is or will become a part of her. This is not internal poison; he is worried that he has hurt the mother in some way. In many ways, Klein is projecting a pre-interpretation of the child’s impulses and trapping the boy in a particular psychoanalytic mindset. In this, I am reminded of Zizek’s big Other and how it manifests in Plath’s The Bell Jar; Esther’s Other is the psychoanalytic platform, the established social norm with which one signs (ha) a contract.

I was also reminded of Marguerite Duras’ The Malady of Death. This is a strange experimental book, consisting of only 60 pages of enlarged text. The platform on which we establish our protagonist is the self – in other words, the reader (individually and collectively, each at once but also not at the same time). Duras addresses the audience directly in second person; “You” are the thing that makes the book happen. Without the “You” Duras’ statements about ‘what you do’ could not exist. “You” are the subject. “You” are the actor of the great play. Imagine an audience; everyone in it has the capacity to be (and already is) the “You” which Duras addresses. And “You” are therefore ambiguous, transitory; but you are also an aggressor, you do things to the woman (who is the primary object, the only other “character” that appears) inside the book, you do things to the book that are unconscious as you read. “The body’s completely defenseless, smooth from face to feet. It invites strangulation, rape, ill usage, insult, shouts of hatred, the unleashing of deadly and unmitigated passions.” (16)

“You” are like an infant yourself. There is a distance established between the self and the “you” on the page by the virtue of narrative. “You” don’t seem to understand how the female works, what she is for, everything is experimental and there is a very real sense that sexual attraction is not present; that violence is latent but always stewing underneath the skin.

“You look at her. She’s very slim, almost frail. Her legs have a beauty distinct from that of the body. They don’t really belong to the rest of the body. You say: You must be very beautiful. She says: I’m right here in front of you. Look for yourself. You say: I can’t see anything. She says: Try. It’s all part of the bargain. You take hold of the body and look at its different areas. You turn it round, keep turning it round. Look at it, keeping looking at it.” (16-17)

“Out of the half-open mouth comes a breath that returns, withdraws, returns again. The fleshly machine is marvelously precise. Leaning over her, motionless, you look at her. You know you can dispose of her in whatever way you wish, even the most dangerous. But you don’t Instead you stroke her body as gently as if it ran the risk of happiness. Your hand is over the sex, between the open lips, it’s there it strokes. You look at the opening and what surrounds it, the whole body. You don’t see anything. You want to see all of a woman, as much as possible. You don’t see that for you it’s impossible.” (35-36)

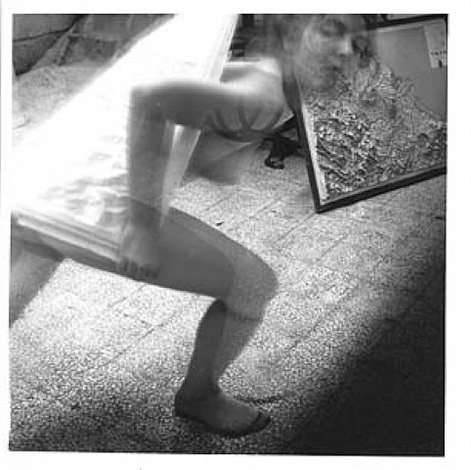

This echoes Lacan’s conception of courtly love, his understanding of the lack in the woman which the man consistently attempts to find identity in, so as to validate his existence through her. He uses her for this, but can never be satisfied because as Other, she is merely a sight of recognition which is always there but also not there; she is eternally elusive. Imagine her, as if she were the ghostly Francesca, partially shielding herself from the gaze with a kind of fabric just as she moves in rebellion, in order to disrupt that gaze further…

[Space 2, Providence, Rhode Island, Francesca Woodman]

“There’s nothing left in the room but you. Her body has vanished. The difference between her and you is confirmed by her sudden absence.” (52)

Is there a way that we can interpret The Malady of Death in terms of Klein? “The Malady of Death is inside you,” says the woman, claiming that you can never start to “begin”. The phallus has been passed down from the father to the son, the progeny of Adam being eternally embedded in the male physiognomy. “You” wish to kill her (“While she lives she invites murder.” (33)) because the possibility of her disappearance and the fact that “you” see your own self projected on her speaks to your own being. “You” see her in relation to the gaping “black sea”, which you look out upon: “It occurs to you that the black sea is moving in the stead of something else, of you and of the dark shape on the bed.” (28)

“You look at the malady of your life, the malady of death. It’s on her, on her sleeping body… You don’t love anything or anyone, you don’t even love the difference you think you embody.” (32-33) Though “your” emotions are practically nonexistent throughout the book, you finally develop to where you can cry about your condition (46), “[going on] with the story about the child” (49). Like Dick – as Klein works with him over time – “You” have finally found some measure of (Lacanian) symbolic articulation – you have found a language of expression [in some capacity], even if the woman does not understand your words.

According to Klein, the expression of anxiety and libidinal interest (that is, of the unconscious phantasy) sets going the mechanism of identification, the forerunner of symbolism, which arises out of the baby’s endeavor to rediscover in every object his own organs and their functioning. Sadism predominates at the phallic stage of development (the third of Freud’s stages, though Klein prefers the idea of ‘position’ rather than ‘stage’, conceptually allowing for “much more flexible to-and-fro process[es] between one and the other” (Hinshelwood, 1991)). At this position, the child wishes to possess every part of the mother and destroy her completely by every weapon of sadism. Klein believes that the child has expectations about what is inside the mother. First, the child expects to find (a) the father’s penis, (b) excrement, and (c) children – and all of this he/she associates with edible substances. The child fears the penis, the breasts, the vagina, and so the child represents these things in objects. The child’s first understanding of sex is that the father becomes one with the mother, and so sadistic acts directed at various objects are aimed at both parents. Anxiety is felt out of fear of punishment, which becomes internalized because of oral-sadistic introjection of the objects which goes to form the moral standards by which the ego operates (the super ego).

The boy that she analyzes appears to be unable to express this anxiety; that is, she concludes, the anxiety he felt about penetrating the mother’s body and what would be done to him [particularly by the father’s penis] – for apart from all else, he was only interested in trains, stations, door-handles, doors and the opening and shutting of them; Dick did not display any interest in most other objects around him. Further, he put a stopper on his ability to actually be aggressive, like normal children. This was manifest because he would not eat properly, and at four years could not hold scissors, knives or tools, but could happily utilize a spoon. Klein hypothesizes that all of these worked in defense against sadistic impulses to mutilate the mother’s body. This had resulted in “the cessation of the phantasies and the standstill of symbol formation.” He was unable to represent his phantasies in the world around him. Klein’s imposition of representation for him helped him begin to act more like the typical child who expresses anxieties in the expected way.

My idea is this: That the “You” of The Malady of Death has failed to express his anxieties in the appropriate way. He knows in some distant way that this is related to the opposite sex but does not understand it, having only the black (meaning dark, empty, expressionless, void-like) sea as company before the woman comes. There is of course Lacan tied up in the interpretation, which I discussed earlier. But with the introduction of woman, we see that the man still cannot establish proper contact with the woman because his phantasies have been repressed to the point that they do not even come to the fore of consciousness once he begins to do things to her that are fundamental to such phantasies. He knows he can kill her, but doesn’t move to; instead, he uses her, objectifies her, until finally he is able to weep before her about his own death. In no way do You recover from the sufficient maltreatment undergone as an infant (that is, the failure of the parents to meet the requirements of each development stage); rather, You find yourself eternally stuck within the pre-oedipal death drive, represented by the house you never leave – which the woman enters, and the sea flanks.