What is looking and how do we do it? For many of us we do it without thinking; we look, but we do not always know what we are looking at. This tour is meant to illuminate the difference between a passing glance and close looking, and to share minute but precious details that may easily be missed. Through this tour, visitors will discover how the smallest detail can change the way we see and understand an artwork.

Tour by Naomi Romm, Hampshire College ’16, Institute for Curatorial Practice Intern, Summer 2016

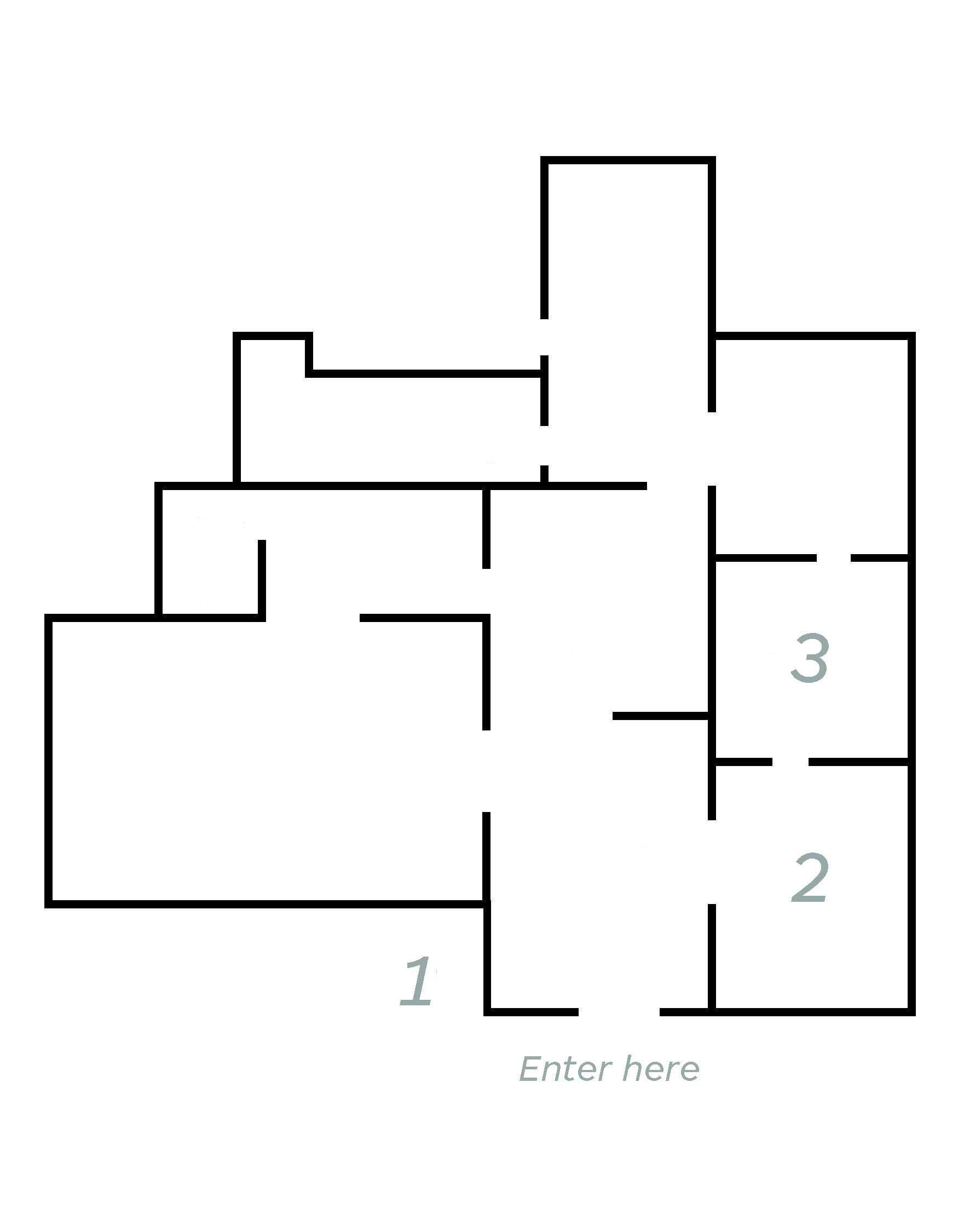

1.

Woman’s saddle with stirrups, late 19th–early 20th century, Apsáalooke (Crow), leather, glass beads, paint and iron, Joseph Allen Skinner Museum, Mount Holyoke College

Patches of animal hide have been stitched together to create the graceful shape of this saddle. Looking closely at the border, where the saddle would sit atop the horse’s back, you will notice a decoratively scalloped edge. This smaller saddle was intended for use by a female member of the Apsáalooke tribe of the Yellowstone river valley. Horse riding allowed for more efficient hunting and transportation. The large herds which the Apsáalooke kept were central to their sustenance. Horses, as well as the saddles used to ride them, could signify prestige and strength.

Look closely at the intricate bead-work which creates an hourglass shape with curvilinear, leaf-like forms that comprise the negative space. This stitch-work is known as an “overlay”, or “crow stitch” and its invention is often attributed to the Apsáalooke. The stitch can fill in large areas with parallel lines and is especially tight and secure. Blue, like the various tones seen in this beaded pendant, was a popular color for bead-work since it was often symbolic of the sky. Surrounded by a field of white beads, the hourglass shape is made especially evident and the colors appear remarkably vibrant. Smaller details, including two strings of alternating blue and white beads, a few jingling bells, and a red feather give the saddle its individual character.

2.

Handled jug with princely figures, late 12th–early 13th century (Seljuq Period, 1037–1196), Persian, stonepaste with white glaze, overglaze enamel pigments, and gold (mina’i ware), Gift of the Arthur M. Sackler Foundation, 2012.40.15

This piece of turquoise mina’i ware is decorated with a band of ten, seated royal figures. Look closely at these men. What do you notice about their dress? Their royalty is indicated by the presence of tiraz—the gold arm bands worn on their upper arms. Tiraz were honorific embroidered bands given to courtiers and other dignitaries by the ruler. Walk around this object and look closely at the individual figures. Although almost identical, each figure is distinguished by the unique fabric of their robe, decorated variously with geometric shapes, cloud scrolls, and other patterns typical of the period. Do you see any other forms of decoration on this drinking vessel? There are two calligraphic inscriptions around the outside of the rim and on the rim’s interior. On a vessel like this, calligraphy usually offers good wishes, fortune, and luck to the owner of the object.

To read more about tiraz, click here

Turn left to enter the terracotta-colored gallery…

3.

Faustina the Elder, second half of the 2nd century CE, Roman, marble, Purchase with the Art Acquisition Endowment Fund, Marian Hayes (Class of 1925) Art Purchase Fund, Susan and Bernard Schilling (Susan Eisenhart, Class of 1932) Fund, Warbeke Art Museum Fund, Abbie Bosworth Williams (Class of 1927) Fund, 1997.15

Faustina the Elder, second half of the 2nd century CE, Roman, marble, Purchase with the Art Acquisition Endowment Fund, Marian Hayes (Class of 1925) Art Purchase Fund, Susan and Bernard Schilling (Susan Eisenhart, Class of 1932) Fund, Warbeke Art Museum Fund, Abbie Bosworth Williams (Class of 1927) Fund, 1997.15

AND

Bartolomeo Cavaceppi (Italian, ca. 1716–1799), Bust of Faustina Minore (Faustina the Younger), ca. 1795, marble, Purchase with the Belle and Hy Baier Art Acquisition Fund and the Teri J. Edelstein Art Acquisition Fund, 2010.6

While looking at the bust of Faustina the Younger make sure to also look at the bust of her mother, to her left. What differences and similarities do you see? In ancient Rome empresses were known by their distinctive hairstyles. Fashion was inseparably tied to female identity and feminine virtues, so each hairstyle became linked to a particular empress and the qualities that she represented—like motherhood and marital harmony. The hairstyle of Faustina the Elder became popular among Roman women, who adopted it to demonstrate their admiration of Faustina and her virtues. Faustina the Younger, Faustina the Elder’s only surviving daughter, distanced herself from her mother’s legacy in Roman society by choosing her own distinct hairstyle. Try walking around the busts to note the differences. Faustina the Younger wears her hair drawn back into a low bun, while her mother has hers braided and piled up into a high, crown-like bun on top of her head.

What other differences do you notice? While the bust of Faustina the Elder is a fragment broken off at the neck, Faustina the Younger is complete, with an ornate pedestal. The color of the two busts also sets them apart; notice that Faustina the Elder looks less polished than her daughter, appearing almost dirty in comparison. In ancient Rome sculptures would have been painted to appear more lifelike, and Faustina the Elder retains some of her original pigment. Faustina the Younger, on the other hand, was made in the 18th century from unpainted white marble. The artist of Faustina the Younger’s bust attempted to recreate the style of ancient Roman sculpture, not realizing that the ancient pieces would have been brightly painted.

Naomi Romm, Hampshire College ’16

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.