From the classical to the contemporary, death has long played a prominent role in the production of art. Where does this fascination come from? What is it about death that has kept artists and viewers so intrigued? From images of Christ on the cross to photo documentation of war-zones, death and the causal violence, grief, and destruction that come with it haunt museum spaces and television screens alike. However, what happens when we put death in conversation with the themes of love and resurrection? How is our perception of the word altered?

The works that are explored in this tour do exactly that: they put death, love, and resurrection into a dialogue with each other in the hopes of changing our understanding of all three. We can begin to look at death not through the immortalization and memorialization of the dead body, but instead by shifting our gaze to those left behind and those whose lives are altered by death.

Tour by Naomi Romm, Hampshire College ’16, Institute for Curatorial Practice Intern, Summer 2016

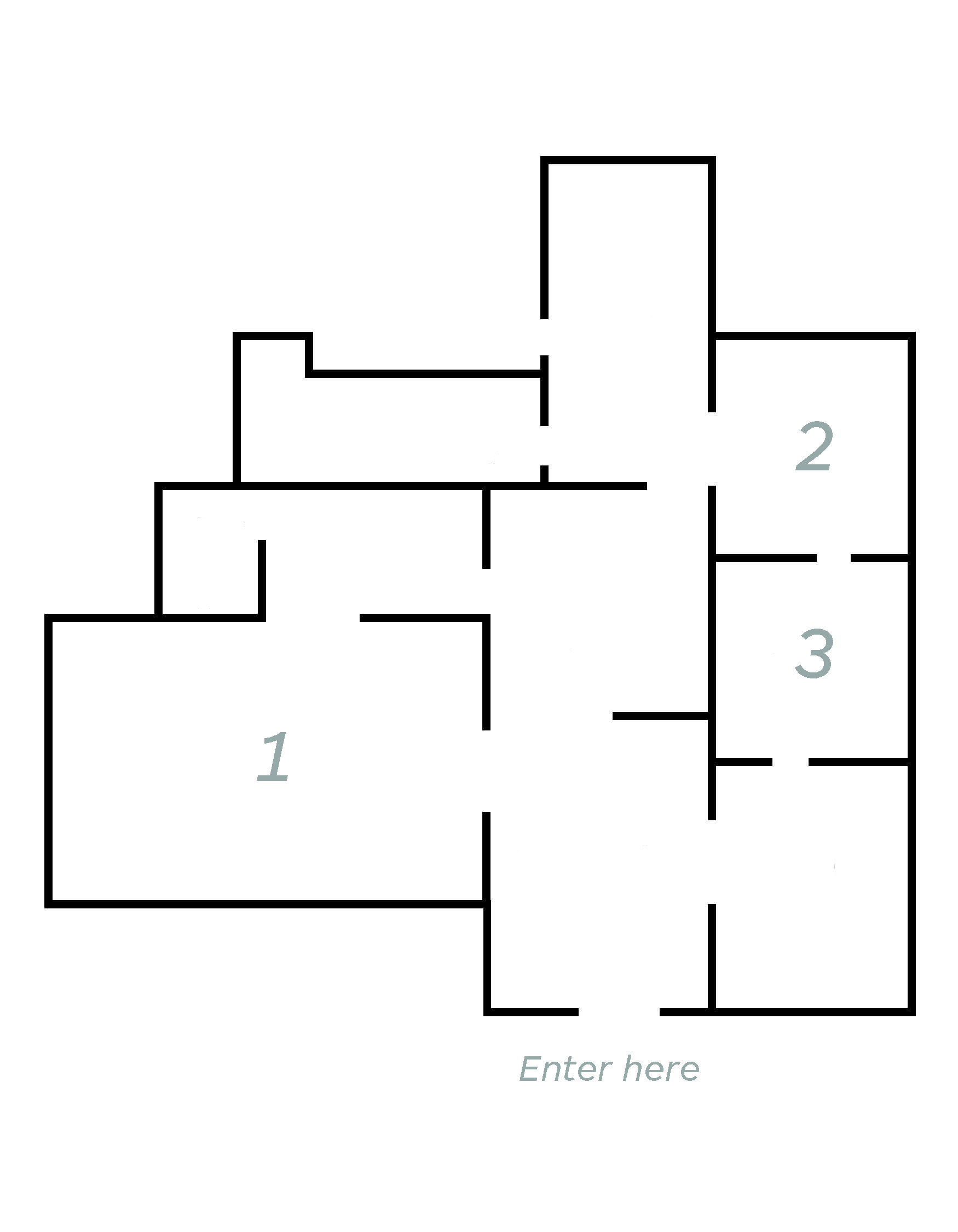

Enter the first gallery and take an immediate left to enter the large white gallery, where you will find your first stop…

1.

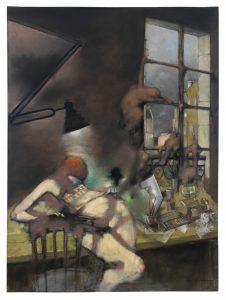

Dorothea Tanning (American, 1910–2012), Still in the Studio, 1979, oil on canvas, Purchase with the Warbeke Art Museum Fund, 2013.11

A nude female figure, presumably Dorothea Tanning herself, reclines across an artist’s table, the surface of which is strewn with her materials: paints, brushes, paper. Look at the window. Cloud-like forms hover like dancing spirits by the window, framing a Paris cityscape. The messy and chaotic room is reminiscent of a typical artist’s studio, in which the occupant is so caught up in their creative pursuit that they lose all sense of organization. Tanning painted Still in the Studio following the death of her husband, artist Max Ernst, and during the time of her return to the United States after decades in France. Begun at the age of 66 and completed over many years, this painting seems to suggest both the death and the rebirth of the artist, who, through her nudity, alludes to the relationship between artist and model, viewer and subject. Through this work, the artist is reborn and resurrected as the source of her own inspiration.

2.

Hendrick Andriessen (Flemish, 1607–1655), Vanitas Still Life, ca. 1650, oil on canvas, Purchase with the Warbeke Art Museum Fund, 1993.14

In this work by Flemish painter Hendrick Andriessen, objects are grouped to conjure ideas of mortality, the fleeting nature of time, and the futility of the pursuit of intellect and power. Thought to be inspired by the reign of Charles I, whose execution took place just a year before its creation, this painting hints at the fall of a great power, particularly through the crown and scepter at the bottom right. If you look closely at the crown you may notice that some of its precious pearls are cracked or missing, alluding to the deterioration of earthly things, and perhaps to the ruler’s demise. In contrast, crowns of holly and wheat, symbols of the life of Christ, remind us of the possibilities of rebirth and salvation. The document at the bottom left, although nearly impossible to read, has been translated as, “Look yourself in the eye, and mark your state if you are not like a bubble, smoke, vapor, or a flower that withers.” However dismal in its stark reminder of the transience of life, Andriessen also reminds the viewer of our collective human condition and the ephemeral nature of being.

For the final stop on the tour, enter the terracotta-colored gallery to your right…

3.

Faustina the Elder, second half of the 2nd century CE, Roman, marble, Purchase with the Art Acquisition Endowment Fund, Marian Hayes (Class of 1925) Art Purchase Fund, Susan and Bernard Schilling (Susan Eisenhart, Class of 1932) Fund, Warbeke Art Museum Fund, Abbie Bosworth Williams (Class of 1927) Fund, 1997.15

Faustina the Elder began her deified life after her death at the age of 40 in 141 CE, when her husband, Emperor Antoninus Pius, elevated her status from deceased empress to civic goddess. The Goddess, or Diva, Faustina represented the characteristics of the ideal Roman woman: her elegance, and her respect for tradition and the sanctity of marriage made her a beloved model worthy of emulation. Coins were manufactured with her portrait, and disseminated widely throughout the Empire. At times, Faustina is shown holding a glove, seen to be a symbol of her husband’s power, while at other times she is illustrated with a phoenix, a symbol of her deified rebirth and her transformation. Walk around her bust; look at the artistry and detail of the carving, especially around the delicate hairs at the nape of her neck. The care and craftsmanship that went into the creation of this sculpture is a testament to her continued popularity and importance after death. A venerated empress and later a goddess, Faustina the Elder’s metamorphic resurrection helped her remain a symbol of feminine aspiration and Roman devotion.

Naomi Romm, Hampshire College ’16