Antiquity Uncovered

“Unparalleled in their accuracy and artistry, photographs were rapidly disseminated among audiences avid to see, rather than merely imagine, history at first hand.” 1

In the years after the inventions by Daguerre and Talbot, photographers began to use the new invention at historic sites. The first camera views of the buried city of Pompeii were daguerreotypes taken by Alexander John Ellis in 1841. At this point, Pompeii was starting to become a tourist attraction as a designated spot on the Grand Tour – the traditional trip taken by young upper-class men through Europe as part of their education.

At the same time, William Henry Fox Talbot’s Calotype was being used to facilitated the multiplication of photographic images. Although the potential of photography for archaeological investigation was great, recognition was slow to take hold. It was not until accomplished amateur photographers like Calvert Richards Jones, Rev. George Wilson Bridges, and Stefano Lecchi was able to pioneer the documentation of Pompeii, that the medium was finally recognized by the monarchy in Naples. As Bridges reported in a letter to Talbot in May 1847, King Ferdinand II of Naples was impressed with the photographs “especially those of the frescoes” and thus granted permission for photographers to photograph throughout the Kingdom.4 The King’s positive reaction suggests that there was official interest in the application of photography to reproduce wall paintings that faded quickly from exposed, which continues to be a problem today.

During his time in Naples, Rev. George Wilson Bridges encountered an Italian calotypist and entrepreneur, Stefano Lecchi. Lecchi had perfected an improved calotype process and was on site with a royal commission as early as 1846 to document excavations. Bridges said of him that “… he makes use of very inferior paper and is more certain of good production…I saw him take 14 one morning at Pompeii without one failure.” 5 Lecchi’s experiments produced several images of Pompeii during a time of experimentation of the medium.

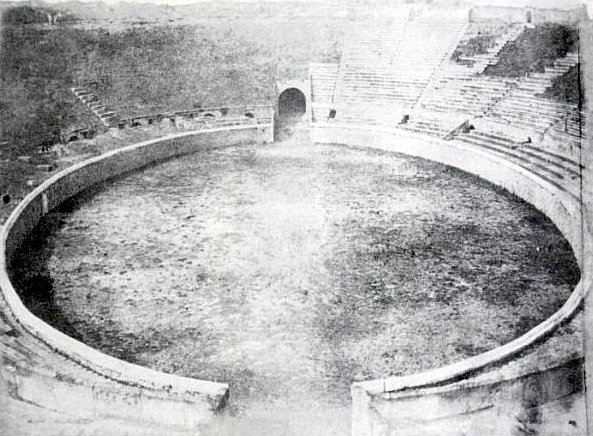

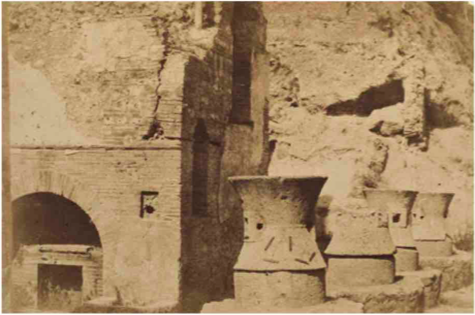

At the same time, Fratelli Alinari (the brothers Alinari), were photographing for the tourism trade in Pompeii. Fratelli Alinari was an Italian firm founded in Florence in 1852 by the three Alinari brothers, Romualdo, Leopoldo, and Giuseppe. Fratelli Alinari became one of the largest and most prolific European photography firms of the 19th and 20th centuries. By 1880, the firm employed over 100 people. Alinari specialized in views of Italy and the reproduction of works of art. Below is an example of one of their photographs. At the time, these images were sold to tourists in Naples and customers abroad to advertise the site. Today, the firm is still well known for its archive of photographs of Pompeii. Although the images are in black and white, it has allowed archaeologists valuable information about the condition of frescoes and parts of Pompeii between the 1860s and 1900.

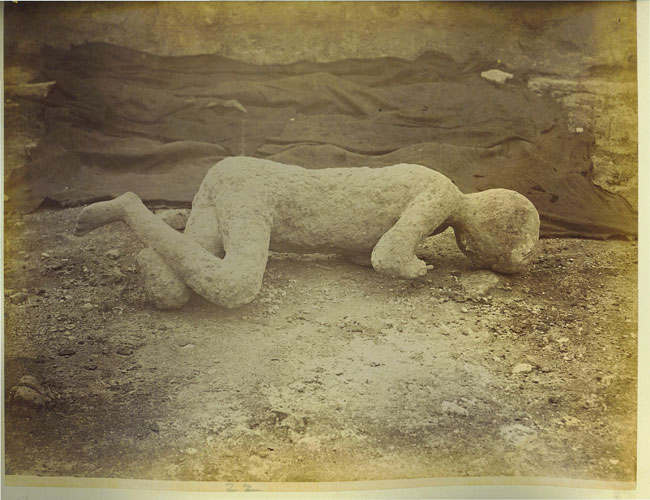

As photography evolved, so did its uses. Initially a tourist tool, it shifted to be a form of documentation. Giuseppe Fiorelli, an Italian archaeologist and Director of Excavations at Pompeii from 1860 to 1875, pioneered a method of archeology that insisted on documentation for recording and preserving Pompeii. He was instrumental in allowing photography to be used during excavations, most notably in his discovery of plaster cast. The injecting of plaster into the cavities left by the imprints of human bodies encased in the volcanic mud of Vesuvius created a cast of the figure. This discovery showing residents of Pompeii preserved in their final moments gave the disaster an all too real face. Fiorelli took advantage of the tourist aspect of this discovery, as well as its scientific advantage. In 1863, he collaborated with a German-born Italian, Giorgio Sommer. 6

Giorgio Sommer was an established photographer in Naples who catered to the tourism industry in Italy. Starting in 1860, he began to survey Pompeii, and by 1863 collaborated with Fiorelli, who helped established him as a premier architectural photographer. Fiorelli turned to Sommer for photographs of his scientific discoveries, such as the plaster casts, and then sent Sommer’s photographs to senior cultural administrators in Florence. Their collaboration resulted in a comprehensive collection of photographs of the major areas excavated, as well as the growing museum collections at Pompeii. Sommer’s photographs are scientific in their approach with an accuracy and archaeological attention to detail that allows his photographs to function as a bridge between archaeological practice, art, and tourism.7

← Previous

Next →

- Szegedy-Maszak, Andrew. Antiquity and photography: early views of ancient Mediterranean sites. London: Thames & Hudson, 2005. ix. ↵

- Coates, Victoria C. Gardner, & Seydl, Jon L., Antiquity Recovered: The Legacy of Pompeii and Herculaneum. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2007. 70. ↵

- Hannavy, John, Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography. New York: Taylor and Francis Group, 2008. 480-81. ↵

- Coates, Victoria C. Gardner, & Seydl, Jon L., Antiquity Recovered: The Legacy of Pompeii and Herculaneum. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2007. 150. ↵

- Ibid. 151. ↵

- Szegedy-Maszak, Andrew. Antiquity and photography: early views of ancient Mediterranean sites. London: Thames & Hudson, 2005. 71. ↵

- Coates, Victoria C. Gardner, & Seydl, Jon L., Antiquity Recovered: The Legacy of Pompeii and Herculaneum. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2007. 76. ↵