Preservation & Documentation

Though the technological advancement of photography, the medium became a household item, accessible to anybody. This freedom of the medium allowed for archeologists to document sites more easily as they changed over time. In the Bay of Naples, this can best be seen at the Villa at Oplontis located near Pompeii. Excavations at the site had been ongoing since the late sixteenth century during the construction of a canal, but due to the geological situation, it was more difficult to uncover the Villa compared Pompeii’s light pumice cover. It was not until 1964 that the Italian Government decided to excavate the site extensively. During this time, Wilhemina Jashemski, an American from Nebraska, undertook research on the gardens at Oplontis.

A professor of Ancient Studies at the University of Maryland, Jashemski was instrumental in pioneering the study of ancient horticulture by using plaster casts similar to those used by Fiorelli at Pompeii, filling the cavities left by trees and plants. She engaged paleobotanists to study the plant materials including pollen and seed-flotation to uncover the kinds of plant species grown at the Villa in 79AD.1 Her involvement at Oplontis Villa A began in June 1964, when Carlo Giordano invited the Jashemski’s to see the remains of Oplontis at Torre Annunziata, under excavation by the Superintendency for Naples and Caserta. Between 1964 and 1971, Jashemski excavated the gardens of Pompeii, Boscoreale, and Oplontis. Her husband, Stanley, a noted physicist, collaborated with her, and additionally documented the excavations with extensive photography, ultimately producing more than 30,000 photographs, until his death in 1982.2

During the excavations, Photography was the single most important form of documentation for the Jashemskis’ work at Pompeii. Stanley was integral in documenting Wilhelmina’s discoveries, as well as everything else occurring at the Villa, even when he was not supposed to be. He used mainly Kodachrome film to document the archeology. Kodachrome is a slide film invented in 1936 that allows one to project the image from either slide through a projector. The price of the film was lowered in the 1950s allowing the new medium to be more cost efficient for consumers. The couple started to use Kodachrome as early as 1955 to document ancient gardens and continued to use the film into the 1980s. Because of the film’s chemical makeup, even after seventy years locked away in storage, Stanley’s Kodachrome slides have remained intact and vivid. Jashemski additionally used black and white print film but his use of color was a huge leap in technology that offered archaeologists the advantage of seeing frescoes in their full array of colors.3

In addition to the use of Kodachrome, Wilhemina Jashemski used aerial photography via a balloon in order to capture the layout of the Villa in relations to its gardens and vineyards. The photographs allowed for Jashemski to see the locations of root cavities and contours from a birds-eye-view. This technique was first used in 1973 and again in 1977 in collaboration with Julian and Eunice Whittlesey, of the Robin Lee Whittlesey Foundation, who used both a Hasselblad camera and 8-meter kite balloon to capture both black-and-white and color images. 4

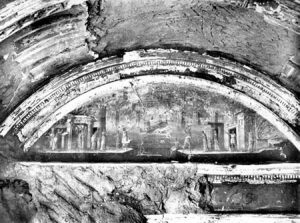

Stanley’s photographs documented more than just Wilhemina’s excavations or root cast cavities. He shot everyone and everything including the crew, the bulldozers, and the frescoes emerging from the hardened volcanic mud. Because of this, it is now possibly to reconstruct the procedure of the excavations in 1966 through Stanley’s photographs. They have allowed archeologists documentation of what frescoes looked like when they were first discovered. Some have since faded away due to exposure and these photographs act as the only record of the lost works. For example, the fresco in the tympanum above the north alcove of cubiculum 11 was photographed by Stanley shortly after its discovery around 1966. The fresco has since faded away but modern technology has allowed for the recreation of the fresco using Stanley’s photographs. 5

← Previous

- “The Oplontis Project.” The Oplontis Project. 2012. Accessed March 21, 2017. http://www.oplontisproject.org/. ↵

- McKee, Jim . “Wilhelmina Jashemski is a Nebraska author you’ve never heard of.” JournalStar.com. June 13, 2010. Accessed March 22, 2017. http://journalstar.com/news/local/education/jim-mckee-wilhelmina-jashemski-is-a-nebraska-author-you-ve/article_407280f6-75b1-11df-a990-001cc4c002e0.html. ↵

- Clarke, John R., and Nayla K. Muntasser. Eds. Oplontis: Villa A (“Of Poppaea”) at Torre Annunziata, Volume 1. The Ancient Setting and Modern Rediscovery. New York: ALCS E-Book, 2014. http://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=acls;idno=heb90048.0001.001. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵