Catalogue: Introduction

“We must expect great innovations to transform the entire technique of the arts, thereby affecting artistic invention itself and perhaps even bringing about an amazing change in our very notion of art.”1

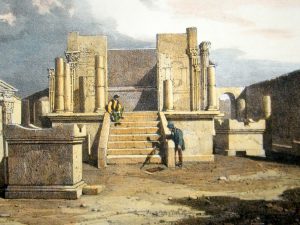

At the dawn of the 19th-century, lithography was at its height. A relativity new technological advancement, it allowed for newly excavated sites in the Mediterranean to be reconstructed in color, on paper, and reproduced in large quantities. During this time, people relied on these reproductions of masterpieces of Western and Ancient art because the art itself was scattered throughout Europe or private galleries. In order to see the works in person, one could take the Grand Tour, but this type of travel abroad was only accessible to the very elite. Due to this, a heavy responsibility was placed on lithography to justly represent art. However, lithography’s days were numbered for it soon gave way to an even more sophisticated means of replication: Photography. Only a few decades after its invention, lithography was soon surpasses by this new invention.2 The photographic process could for the first time bring to light a perfect replica of reality.3

This new medium was introduced to the public in the late 1830s by Louis Jacques Mande Daguerre and William Henry Fox Talbot. Even in the beginning, experts raved about the new advantages of this medium. Francois Arago noticed its contributions to the practice of archaeology, specifically the merits of daguerreotypes for field documentation, “Everyone will imagine the extraordinary advantages which could have been derived from so exact and rapid a means of reproduction during the expedition to Egypt; everybody will realize that had we had photography in 1798 we would possess today faithful pictorial records of that which the learned world is forever deprived of.”

With this new medium, came the dawn of a new field of study: Archeology. Archaeology, like photography, is both art and science, where one takes a journey through time to bring history to the surface in incremental moments. During this formative period, each area of study made major contributions to the other. Photography presented itself as a superior tool for depicting resurrected civilizations, ancient cities, and works of art seen for the first time in a millennia. The circulation of images of these sites, spurred archaeological research and the desire for people to visit these places and to experience their rediscovery. The art historian Adolf Michaelis understood, what was for many, a revelation at the time on the contributions of photography to archaeological achievements, “With the help of photography, we have learned to see anew.”4 Photography transformed archaeology from an innocent curiosity to a self-governed discipline. The camera, most importantly, provided a tool to organize and interpret the new sources of historical information. For scientists, the new faith of science was that “seeing was believing”.5

Daguerre and Talbot could not have foreseen photography’s application to the study of ancient art and architecture. Unparalleled in their accuracy and artistry, in the first four decades of the new medium, photographers documented groundbreaking archaeological excavations. 6

In the early 1840s, the first photographers visited the cultural and historic sites of the ancient Mediterranean. They came with their large cameras, mounted on wooden tripods, and the many chemicals necessary to sensitize and develop images on the spot. Many of these photographers made a name for themselves, taking photographs for the expanding tourist industry or personal interest. The medium was not immediately used for excavation documentation by archaeologists. The first archeologists to use photography primarily for documentation were the Directors of Excavations at Pompeii: Giuseppe Fiorelli, Vittorio Spinazzola and Amedeo Maiuri.

In the later 20th century, the extensive use of photography at Oplontis by Stanley Jashemski played an important role in recording excavations at Oplontis in the 1960s. A physicist, he documentation of his wife’s work, Wilhelmina Jashemski, as well as excavations on the site. The archive of his photographs has since played an important role in the preservation of the site.

As the camera became cheaper and more accessible to the public, the medium has become a part of our daily lives. Think of how today we photograph on our cell phones. Thus, the ‘Photographer’ as a famous personality at these ancient sites has dwindled. The rivalry between Art and Science that Daguerre and Fox Talbot began has progressed to the point where photography has expanded into different fields of study, such as, ancient studies, art history, the fine arts, computer science, physics, and it is even used by NASA on robots on Mars and the International Space Station. However, the medium continues to be an integral tool for archaeologists for recording and preserving ancient sites and antiquities. The work of archaeologists and conservationists has also been enhanced by the advancement of technology with the use of infra-red photography, 3D laser scan technology, spectrographic analysis, x-ray diffraction, high-resolution digital cameras, three-dimensional model through photogrammetry, and sophisticated computer technology, as well as the tiny camera on your iPhone.7 The medium has come a long way and continues to grow and be an integral tool for archaeologists and artists alike.

Next →

- Paul Valéry from Pièces sur l’art, “Le Conquete de l’ubiquité,” in 1931. Benjamin, Walter. The work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction. United States: Prism Key Press, 2010. 1. ↵

- Bergmann, Bettina. Returns to Pompeii: Interior space and decoration documented and revised 18th-20th century. Stockholm 2016. p. 186-7. ↵

- Benjamin, Walter. The work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction. United States: Prism Key Press, 2010. 5. ↵

- Szegedy-Maszak, Andrew. Antiquity and photography: early views of ancient Mediterranean sites. London: Thames & Hudson, 2005. 39. ↵

- Ibid. 42. ↵

- Ibid. 41. ↵

- “Archaeology.” Pompeii and Herculaneum Revision. Accessed March 22, 2017. http://pompeiiandherculaneumcc.weebly.com/archaeology.html. ↵