Anthropology and Collecting in Australia

Professor Baldwin Spencer is credited for being the “father of Australian anthropology.” Together with Francis James Gillen, they traveled throughout Australia studying Indigenous Australians (1). He was originally trained as an evolutionary biologist (Darwinism) which still influenced his beliefs. Even though he was thought to be an advocate for Aboriginals, he still saw them as “dehumanized ‘survivals’ from an early stage of social development.” (2) His racist beliefs and problematic approaches to Anthropology have resulted in many items being attributed to him personally instead of the Aboriginal people/ groups who created them.

Partially because of this issue, Baldwin Spencer is one of the most effective search terms we used. Searching his name yields ninety search results in the British Museum’s online collection. This means he has more objects attributed to him personally than any ethnic group in Australia. Of course, this is in part due to the breadth of his research, but considering he did not produce any of these objects it is a significant dynamic.

Sixty-five items appear when the terms “Baldwin Spencer” and “Northern Territory (Australia)” are used in the “Person/Organization” and “Place” filters, respectively. These are the items listed.

Armlets Attributed to Marra

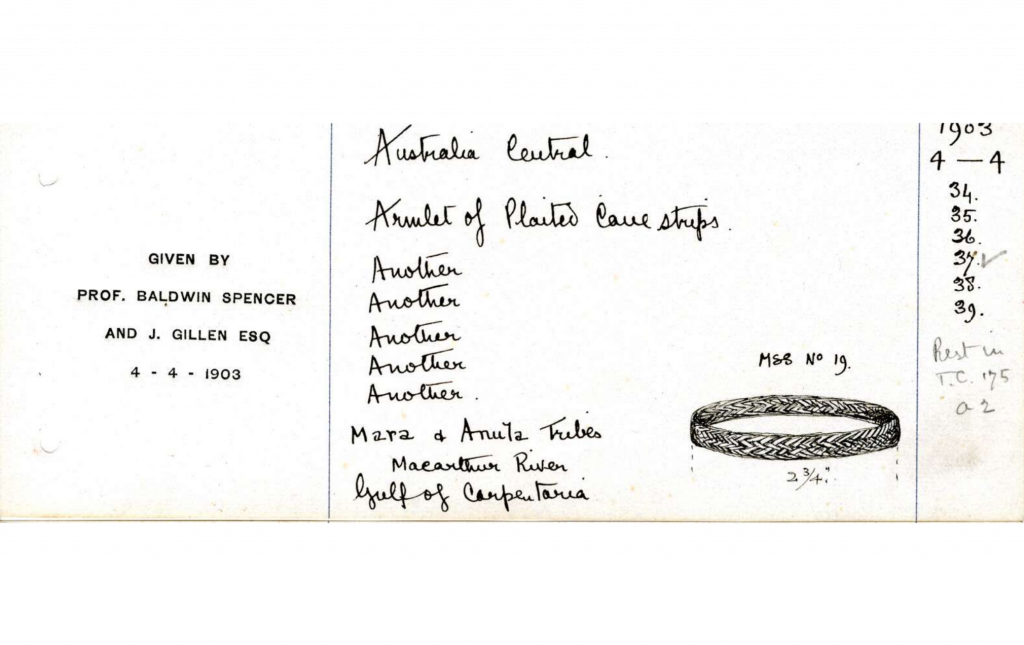

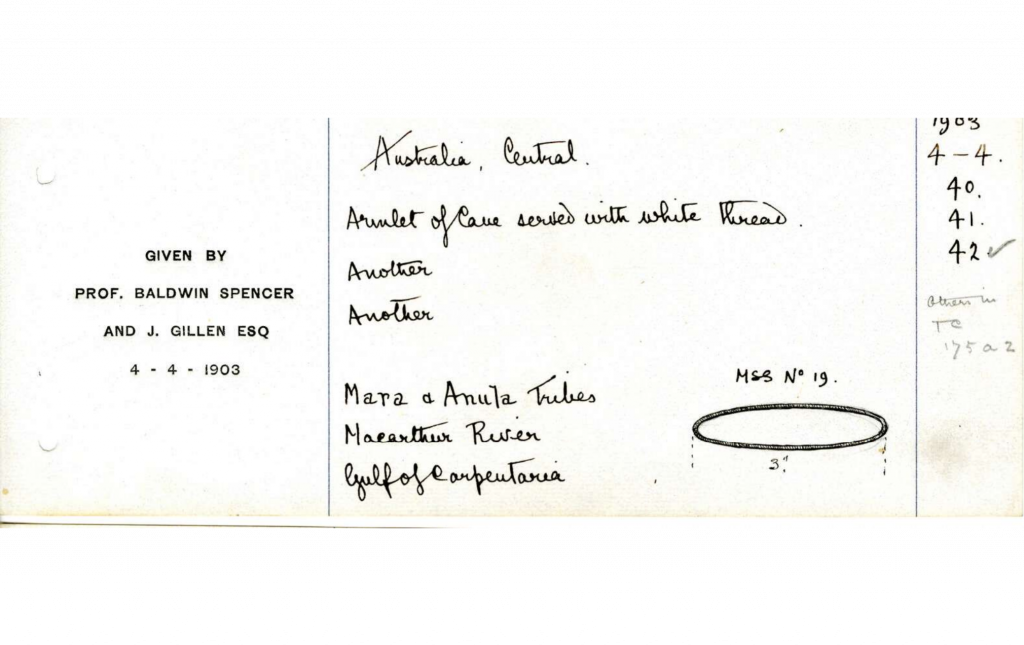

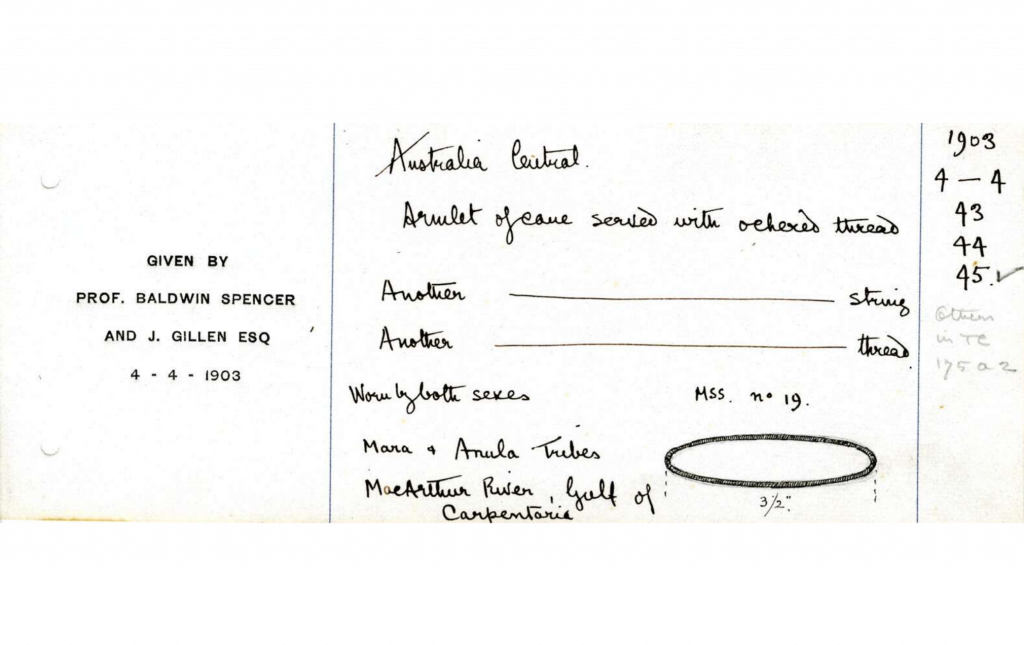

Using the search term Mara and specifying “Northern Territory (Australia)” in the place filter, we were able to find several armlets Professor Baldwin Spencer acquired. Each group of armlets is documented in a postcard written by Professor Spencer and/ or his assistant.

Armlets made of Cane: Armlets 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, and 39

Armlets Made of Cane and Thread: ARmLETS 40, 41, And 42

Armlets Made of Cane, Thread, and ochre: Armlets 43, 44, and 45

- The earliest we can trace custody of these armlets is their acquisition by Professor Spencer in 1903 at the Gulf of Carpentaria by the MacArthur River.

- The British Museum classifies these armlets as produced by both Anula and Mara, just like the postcard provided by Professor Spencer.

- Each item is attributed to a particular ethnic group, but we are left with questions about these categorizations. The dates on the postcards mark the date of donation to the British Museum and many of the objects were acquired at similar locations. Some objects (including some of the armlets) were attributed to multiple groups. It is likely these items were traded between language groups (Senior).

Pipe from Mara

The pipe was found in the British Museum collection by using “Mara” and “Baldwin Spencer” together as keywords. “Mara” alone did not help our search because it is also a language group in Myanmar, so we had to add another word to tie “Mara” to Australia. Using “Australia” or “Indigenous Australia” did not result in the pipe coming up which may be because the identification card does not actually use or tag the words “Australia” and “Indigenous” in its description and information.

The pipe was acquired in 1903 by Professor Spencer (same as the armlets) which makes sense since it seems he was already in the area and learning about the culture.

Macassans

With the help of Professor Kate Senior (University of Newcastle), we were able to make the connection between Indigenous Australia and the Macassans (Makasar) people from Sulawesi which is today’s Indonesia (3). Trade between the two groups started around the 1700s, predating Europeans a few hundred years. Every year hundreds of Macassans would sail over to the Arnhem coast to fish for trepang (Sea cucumbers). Sea cucumbers were important for both the Aboriginals because they were boiled and dried for medicine. The Macassans wanted the echinoderm to trade with China who regarded the animal as a delicacy and aphrodisiac. The Macassans would trade the Aboriginals tobacco, pipes, calico, and metals for the sea cucumbers. (4)

There was not just a transfer of materials, but also culture. The Macassans would camp on the coast for months starting in December, working with Indigenous Australians and then leaving in April. Some words that the Macassans used are still used in Aboriginal language such as “rrupia” which means money. In addition, the introduction of metals influenced culture because it was the first time Aboriginals were able to make blades for knives and axes, ultimately making their everyday life a little easier. (5)

Trade and connection to Indonesia was severed with the creation of Australian Government. The last Macassans to came over to Australia was in 1907. (6)

Just some tidbits from ‘the field’: there are still a handful of old men who use those Macassan pipes and a few years ago there were some old women who knew how to make those armbands. I have one that an elder made for me but, she has passed away. I’m not sure if there are any female elders today who can still make them.

Ngukurr linguist Greg Dickson (7)

Tree Burial Photograph taken at Roper River 1910

Using the search term “Roper River,” we found three objects in the British Museum’s online collection; a book, a photograph, and a boomerang. The item most likely connected to Ngukurr is a black and white gelatin silver print photograph of a tree burial taken by R.D. Joynt in 1910. Joynt was a founding Missionary of the Roper River Mission established in 1908. In the photo, a deceased loved-one is wrapped in a bark cloth and placed in a tree on the Roper River.

On the advice of Professor Kate Senior (University of Newcastle), we decided that this photo will not be exhibited on this website (8). This photograph is an inappropriate objectification of sacred burial practice and the individual whom it is for. It is unclear and unlikely that consent was given to the photographer by the Aboriginal Australian Ancestor’s kin. It also captures a burial practice that is not meant for the consumption of non-Indigenous individuals. This photograph and its public availability in the British Museum’s collection is relevant to an ongoing conversation about the need for regulated and respectful non-Indigenous access to Aboriginal Australians’ sacred and traditional knowledges.

Ethical Access Guidelines and Conversations

There is a standard practice for conducting research and accessing photographs in Australian Aboriginal cultural heritage as outlined by the Returning Photos: Australian Aboriginal Photographs from European Collections project. This project uses ethical guidelines from multiple sources, such as the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) Code of Ethics for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Research, to guide ethical access to Indigenous people’s cultural knowledge.

Within these ethics, there are main principles that guide accessibility listed in the website’s Cultural Protocol section. These assert Indigenous peoples’ “right to determine how they are represented…[and their] right to manage their sacred and traditional knowledge in accordance to their customary law” (9). This project requires non-Indigenous researchers to seek and have evidence of permission from the relevant Indigenous Community before having access to this knowledge. This is an important step institutions must take to help protect and respect Aboriginal communities’ cultural heritage.

Exhibiting this photograph and the online collection’s public access to it goes against such guidelines. A standard of institutional integrity has been set by the project mentioned above. We believe all institutions holding Aboriginal Australian and other Indigenous photographs and sacred objects, like the British Museum, have a moral obligation to take the necessary actions toward ethical and respectful access.

For more information on the Cultural Protocols and the mentioned project, please see the Returning Photos: Australian Aboriginal Photographs from European Collections website linked here: (https://ipp.arts.uwa.edu.au/)

works cited

1. “Sir Baldwin Spencer.” Britannica Encyclopedia. Britannica Encyclopedia, July 20, 2020. Accessed February 23, 2021. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Baldwin-Spencer-British-anthropologist

2. Mulvaney, JD, “Spencer, Sir Baldwin (1860-1929).” Australian Dictionary of Biography. Australian Dictionary of Biography, 1990. Accessed February 23, 2021. https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/spencer-sir-walter-baldwin-8606

3. Professor Kate Senior, personal communication, February 17, 2021.

4-6. “Trade with the Makasar.” National Museum of Australia. National Museum of Australia, May 22, 2020. Accessed February 23, 2021. https://www.nma.gov.au/defining-moments/resources/trade-with-the-makasar.

7. Ngukurr linguist Greg Dickson, Zoom conversation, March 3, 2021.

8. Professor Kate Senior, email conversation, February 25, 2021.

9. “Cultural Protocols.” Returning Photos: Australian Aboriginal Photographs from European Collections. Last Modified (n.d.). Accessed February 28, 2021. https://ipp.arts.uwa.edu.au/cultural-protocols/.

We would like to be involved/included if possible, in future use of the material. Please contact this individual as point-person for our group: dear22m@mtholyoke.edu