The 1948 Arnhem Land Expedition was an expedition led by a group of American and Australian explorers. The American researchers were made up of individuals from the Smithsonian Institution and National Geographic. The researchers had three camps; one in Umbakumba, one in Yirrkala, and one in Oenpelli (now Gunbalanya). There was an initial plan for an additional base at Roper River Mission, now Ngukurr. This plan proved “too ambitious” and was abandoned (Thomas 2010: 143-170). Though the expedition had no official plans to visit Roper River Mission, mentions of the mission are still made in museum collections.

Members of the expedition arrived at Umbakumba in April of 1948. It was here that they met Gerald “Jerry” Blitner. Blitner, whose father was white and mother was Aboriginal, spent the first several years of his life at Roper River Mission. At the age of four, though, he was taken from his mother to a mission on Groote Eylandt for “half-caste” children. He worked in the expedition as “what is best thought of as a cultural broker” (Thomas 2011:377-402).

“Determining exactly how many ethnographic objects were collected for the American–Australian Scientific Expedition to Arnhem Land is a difficult task. A complete inventory was not made in 1948. The objects were distributed across many institutions. For various reasons they might not have been catalogued at the time, which increased the possibilities of errors. Equally difficult to establish is what items, and how many, went to which institutions.”

(Thomas 2011:214-215)

Fish!

[slideshow_deploy id=’105′]

Though the expedition did not end up using Roper River Mission as a base, Jerry Blitner made a trip there in August of 1948. During this trip, he collected many fish from a billabong just 3 miles north of the mission.

- Ambassis macleayi Macleay’s Glass Perchlet

- Arius leptaspis Salmon Catfish

- Glossamia aprion Mouth Almighty

- Melanotaeniea splendida inornata Rainbow Fish

- Melanotaenie splendida Rainbow Fish

- Glossamia aprion 2 Mouth Almighty

- Glossamia aprion 3 Mouth Almighty

- Glossogobius Tank Goby

- Glossogobius aureus Golden Tank Goby

- Oxyeleotris selheimi Giant Gudgeon

- Oxyeleotris lineolatus Sleepy Cod

- Glossogobius giuris Tank Goby

- Oxyeleotris lineolatus Sleepy Cod

- Toxotes chatareus Spotted Archerfish

- Ambassis agrammus Sailfin Glass Perchlet

- Amniataba percoides Barred Grunter

- Leiopotherapon unicolor Spangled Perch

- Strongylura kreffti Long Tom (Needlefish)

- Neosilurus hytrilii Hyrtl’s Catfish

- Anodontriglanis dahli Toothless Catfish

- Tandanus rendahli Rendahl’s Catfish

- Thryssa scratchleyi New Guinea Thryssa

- Nematalosa erebi Australian River Gizzard Shad

(Common names provided by Froese, Pauly, 2020.)

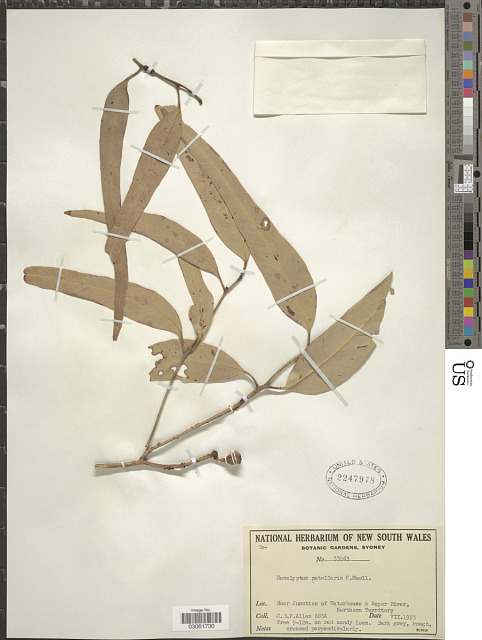

Plants

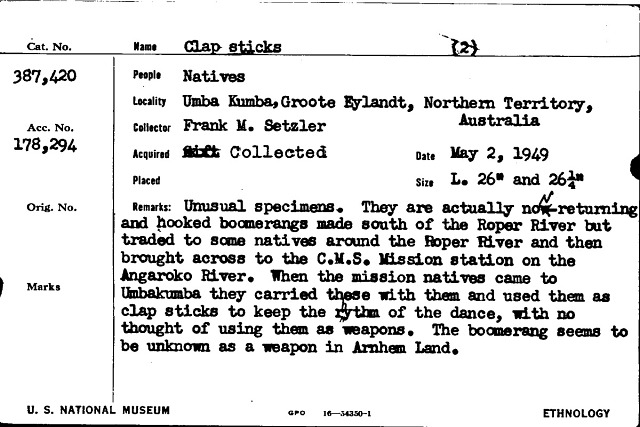

Clap Sticks

Link to the original digital item.

Bark Paintings

“One hundred sheets of bark (of unspecified dimensions) were cut by Milingimbi staff during a visit to Roper River in February 1948, and were sent to Groote Eylandt for the Expedition’s use”

(Thomas 2011:41)

[slideshow_deploy id=’211′]

(Click on the image, to go to/ be linked to the Smithsonian’s page for items in slideshow )

While these bark materials do not directly relate to Ngukurr, we found this to be as close as we could get to yielding some possible connections to Ngukurr — especially since searching “Ngukurr” yielded 0 results in the Smithsonian’s Anthropological Collections database. By utilizing this book source, in particular the chapter 2 mention of bark, we were able to find a possible connection between the Roper River Mission and the Groote Eylandt Expedition. Using “Groote Eylandt” as a keyword in our search yielded more bark-based results, specifically, 21 bark paintings and 4 painted bark garments. The marks or etching made in the bark probably does not correlate with Ngukurr culture. However, the bark itself may be traceable back to Ngukurr because it was cut at Roper River Mission and “secured” by the Darwin Native Affairs Administration Office.

Note: We would like to again stress that the paintings on the bark were done at expedition camps like Umbakumba and Yirrkala. However, the bark used for these paintings was cut at Roper River Mission.

[slideshow_deploy id=’345′]

Photo copy/pasted here from SI collections database. Last accessed February 28, 2021. Available at: https://collections.nmnh.si.edu/search/anth/ (using keyword search with words, “Northern Territory Basket” – results yield baskets from region of Northern Territory, Australia, and some of the catalogs have images available to view).

The Smithsonian also houses many objects from Northern Territory that are not near Ngukurr; for example, there is a large collection of “baskets” (dilly bags/yena) from Milingimbi Island, an island directly north of Ngukurr, that were collected by Frank Setzler. In reading “A Short History of the 1948 Arnhem Land Expedition” by Martin Thomas, there are a few notable things.

“Works collected on the Expedition are held in institutions that were not part of the original distribution scheme. For example, the Kluge-Ruhe Collection at the University of Virginia has one of the paintings on paper that appeared in Volume 1 of the Records of the American–Australian Scientific Expedition to Arnhem Land. It was purchased by John Kluge in 1995 from Museum Art International. It is not known where or how Museum Art International obtained the painting.”

(Thomas, 2011:229)

Due to this excerpt from the book, we have contacted the curators of the Kluge-Ruhe collection to inquire about any paintings or other items that they may hold that were taken during the Arnhem Land Expedition of 1948, but those we contacted have yet to reply to our inquiry as of March 2021.

National Geographic

The Arnhem Land Expedition of 1948 was a collaboration between the Smithsonian Institution, National Geographic, and select other Australian organizations; due to archive searches and readings, we thought there were likely pictures of Ngukurr taken by Howell Walker (expedition photographer) in the National Geographic archives. We contacted curators at the National Geographic Archives collection, and they responded that there are photographs from Roper River; these photographs have not been digitized yet.

National Geographic has a digital archive of all their magazines. This archive can be accessed through a NatGeo subscription. Libraries may also provide free access. For individuals with a broader interest in the 1948 expedition, there were several articles written by individuals of the expedition.

Note: For more information on how to navigate the Smithsonian databases, we found this helpful guide: Here

We would like to be involved/included if possible, in future use of this material. Please contact this individual as point-person for our group: aftan22g@mtholyoke.edu

Another reference: May, Sally K. Collecting Cultures: Myth, Politics, and Collaboration in the 1948 Arnhem Land Expedition. AltaMira Press 2009. Available at https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.proxy.mtholyoke.edu:2443/lib/mtholyoke/detail.action?docID=467169

Citations

Froese, R. and D. Pauly. Editors. 2020. FishBase, World Wide Web Electronic publication. www.fishbase.org, (12/2020)

Thomas, Martin. “A Short History of the 1948 Arnhem Land Expedition.” Aboriginal History, vol. 34, 2010, pp. 143–170. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/24047029. Accessed 26 Feb. 2021.

Thomas, Martin, and Margo Neale, editors. Exploring the Legacy of the 1948 Arnhem Land Expedition. ANU Press, 2011. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt24h9p1. Accessed 26 Feb. 2021.