“For tens of thousands of years, possum skin cloaks protected First Peoples from cold and rain, mapped Country, told, and held, stories.”

The Timeless and Living Art of Possum Skin Cloaks

Possum Skin Cloaks as Markers of Identity

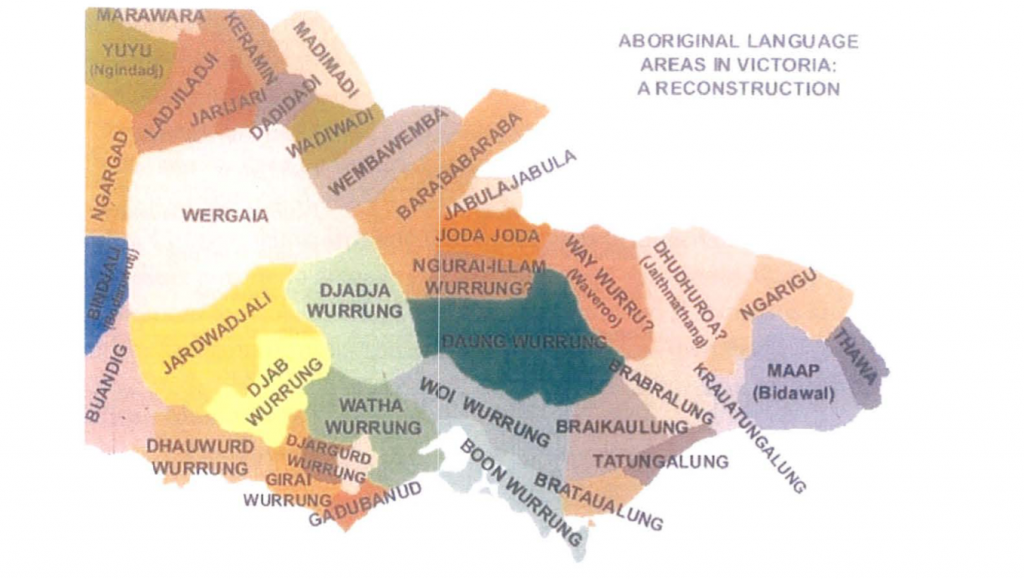

Possum skin cloaks are deeply tied to and entwined with a person’s life story. Beginning at birth, they are made for children and continue to grow with them, depicting significant totems, locations, or symbols relating to that person’s life, community, or culture. As the article “The timeless and living art of possum skin cloaks” points out, possum skin cloaks act as markers of identity since their designs chronicle “the cloak wearer’s journey, their connection to Country and to family.” And in death, a person is traditionally buried with their cloaks. Although possum skin cloaks are markers of a person’s or community’s identity, they have a practical purpose as well. According to artist Vicki Couzens (Gunditjmara), the fibers are hollow in possum fur, unlike kangaroo pelts. This prevents them from freezing and keeps the wearer extremely warm and dry during harsh conditions. Therefore, possum skin cloaks hold significance both for their practical protection and role in sustaining cultural practices and knowledge.

However, due to European colonization, these important markers of identity were among the many cultural practices targeted and stripped away. In “The timeless and living art of possum skin cloaks,” Eileen Maude Alberts, or Aunty Maude, speaks to this while describing how her grandmother was raised with a “mission mentality about not doing anything cultural, not practicing her cultural beliefs.” Despite the violent attempts to prevent the transmission and preservation of cultural knowledge and practices, they have survived and, through revitalization efforts, continue to be kept alive. Although our course has chosen to focus on possum skin cloaks, they are just one aspect of the large, diverse revitalization efforts across Australia

“Before European settlement led to a disruption of traditional lifeways, the making of possum skin cloaks was part of a material culture that contributed to and expressed the emplacement of the Indigenous people on country. The removal of the Indigenous people from country onto missions and stations and the catastrophic population decline that followed led to many aspects of culture that relied on living on country falling into abeyance. The oral transmission of cultural knowledge from one generation to the next was difficult in the fragmented communities that survived. Yet the practice of making possum skin cloaks has survived.”

Helen GibbIns, 2020 “Possum Skins Cloaks: Tradition, Continuity and Change.”

The Revitalization of Possum Skin Cloaks as a form of Cultural Knowledge and Practice

Image by Eugene Hyland

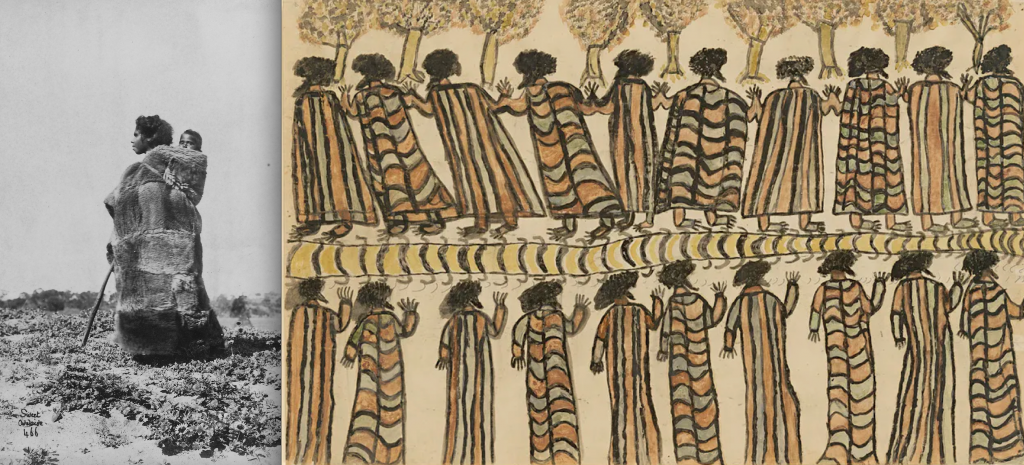

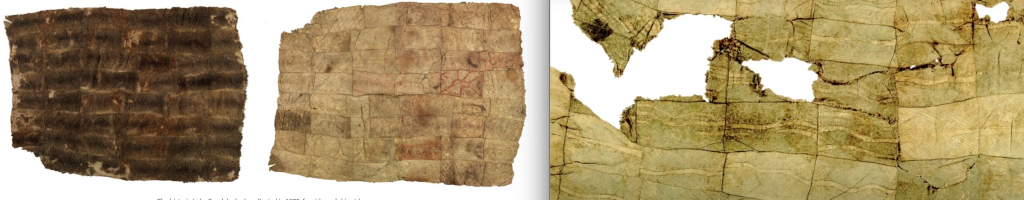

In 1999, two possum skin cloaks were discovered in the basement of the Melbourne Museum in Naarm/Melbourne, Australia. Among the few historical possum skin cloaks left in the world, these two are the only historical cloaks currently housed in Australia. The first cloak belongs to the Yorta Yorta people of north-eastern Victoria, collected in 1853. The second belongs to the Gunditjmara people at Lake Condah, collected in 1872 (both pictured below).

This discovery led artists Lee Darroch (Yorta Yorta, Mutti Mutti, Boon Wurrong) and Vicki Couzens (Gunditjmara) to take up a revitalization project focused on traditional cultural practices, namely possum skin cloak making, in order to make visible that which was previously hidden away. As a result of that project, after working with 36 communities in Victoria, a group of Victorian elders wrapped in possum skin cloaks participated in the opening ceremony of the 2006 Commonwealth Games in Melbourne (pictured below).

“Whilst colonising practices forcibly interrupted many cultural traditions and ways of Being and Doing, contemporary times have seen cultural re-awakening flourishing in Aboriginal communities across south-eastern Australia. Revitalisation of Possum Cloak knowledges and practices as a living legacy in community, is a notable historically significant cultural regeneration phenomenon of our times.”

Dr. Vicki Couzens in “Possum skin cloaks then and now – same same but different.”

Artist Maree Clarke (Yorta Yorta / Wamba Wamba / Mutti Mutti / Boonwurrung) has also participated in reclaiming cultural knowledge through the revitalization of practices such as possum skin cloaks and eel traps. Clarke is one of five artists-in-residence (pictured below) at Mount Holyoke College in Spring 2022 and is the first living Indigenous artist with ties to southeastern Australia to be featured in a major retrospective at the National Gallery of Victoria with her exhibition Ancestral Memories. In collaboration with her family and fellow artists, she is at the forefront of possum skin cloak revitalization and efforts to reclaim south-east Australian Aboriginal art and cultural practices. Clarke’s involvement through the Mount Holyoke College seminar Decolonizing Museums is part of the ongoing revitalization efforts of intergenerational and intercultural knowledge transmission.

“The possum skin cloak coming back is just the most remarkable revitalisation of cultural items I’ve ever seen. From nothing, to extremely common in my eyes, in ten, fifteen years, is just amazing. But we need these kinds of [living] archives to hold information, because it will be up to my generation in 20, 30 years to pass this knowledge down. And if we don’t get information from our Elders now, we could be looking at another serious gap in Knowledge.”

Mitch Mahoney (Boonwurrung / Wemba Wemba / Barkindji), UWA talk 2019.

Artist History

Maree Clarke is a Yorta Yorta/Wamba Wamba/Mutti Mutti/Boonwurrung woman who has been practicing art in Melbourne for over thirty years. Her work, both solo and collaborative, over this time, has been essential to the revitalization of Australian Aboriginal artistic practices that led to the content of this course and the making of this cloak. Though she started with photography, Maree has worked in a variety of mediums, including glass work, sculpture, and jewelry making alongside her work with possum skin cloaks, all of which center traditional Aboriginal cultural and art making practices. Notable exhibitions include her Ancestral Memories exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, which features three meter long glass eel traps suspended in mid-air, a 63-pelt possum skin cloak, a number of kangaroo-tooth necklaces, and old and new photography, amongst other works. Through this exhibit Maree became the first living Aboriginal woman to show an exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne.

Working largely out of her own backyard, Maree has worked with family and community members, including Nicholas Hovington, Kerri Clarke, Mitch Mahoney, and Molly Mahoney, to revive the practices central to her own art. She has traveled both throughout Australia and globally to visit Aboriginal objects held in museums to learn from them and apply their construction to her own work.

Nicholas, Kerri, Mitch, and Molly all maintain their own artistic practices and each of them brings a vital skill-set to the project of making a possum skin cloak, from gathering and processing materials, to construction and design, to burning and painting, to photographing the final product. Together they’ve worked on multiple possum skin cloaks for both family and community and have led similar educational art making projects in schools in Australia and alongside other Indigenous communities.

All five of the artists’ work includes traditional Aboriginal practices and centers the themes of Country, culture, family, and place. Their vast bodies of work demonstrate the ways that these practices are still alive and growing in Australia.

Video: “Maree Clarke Introduces Ancestral Memories” from the National Gallery of Victoria, Naarm/Melbourne

The Living Archive

“The Living Archive” is a way in which Indigenous knowledge and perspectives can continue to be centered and highlighted; it is an alternative to traditional, colonial archival institutions. The Living Archive is both tangible and intangible, encompassing a wide range of things such as Indigenous storytelling, dance, poetry, the establishment of UNSECO world heritage sites, and the revitalization of traditional art-making practices.

Maree’s eel trap art piece is a perfect example of the living archive. Of her work in eel traps, Fran Edmonds said:

“[their] reason for coming-into-being was to aestheticize a traditional form; to demonstrate both the endurance of Indigenous knowledge in southeastern Australia, and the necessity of creative reinvention and adaptation to ensure this continuity… [the] exhibition also publicly declares: despite over 200 years of colonization, we are still here.”

Fran Edmonds et. al., The Living Archive of Aboriginal Art: Expressions of Indigenous Knowledge Systems

Indigenous sovereignty – which is separate from and predates the political definition of sovereignty – is unceded and inalienable; it can be expressed through the process of making, being, and creating. Art-making is an expression of sovereignty because it contrasts and challenges colonial narratives and histories, and is a way for Indigenous people to assert self-determination. The Living Archive and the revitalization of Indigenous art practices are inextricably linked to sovereignty, however, “Indigenous sovereignty” is a subject as diverse as Indigenous and Aboriginal people themselves and can not be easily defined.

Through participating in and/or being exposed to the processes of making that encompass the Living Archive, Aboriginal people not only are exposed to the revitalization of historical practices and the re-centering of Indigenous knowledge, but experience a feeling of going home, as described by Mitch Mahoney.

Group Contact

This group can be contacted by emailing Nora Sylvester at sylve22n@mtholyoke.edu

References & Work Cited

- Edmonds, Fran, et al. “The Living Archive of Aboriginal Art: Expressions of Indigenous Knowledge Systems through Collaborative Art-Making.” Journal of Global Studies and Contemporary Art (Revista De Estudios Globales y Arte Contemporáneo (REGAC)), 17 Aug. 2021

- Gibbins, Helen. “Possum Skins Cloaks: tradition, continuity and change.” The La Trobe Journal, No 85, May 2010. http://latrobejournal.slv.vic.gov.au/latrobejournal/issue/latrobe-85/t1-g-t10.html

- “Experiencing the Oeuvre of Maree Clarke.” Design Anthology, https://design-anthology.com/story/art-maree-clarke-ancestral-memories

- “Maree Clarke introduces Ancestral Memories” YouTube, uploaded by NGV Melbourne, August 10, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hhYGogMQNG0&t=100s

- “The timeless and living art of possum skin cloaks.” Museums Victoria, 2019. https://museumsvictoria.com.au/article/the-timeless-and-living-art-of-possum-skin-cloaks/

- “Wrapped in Culture.” https://rosaliefavell.com/portfolio/wrapped-in-culture/