Systems of Care

A great deal of effort and knowledge went into keeping these birds. The aviary prompted the creation of an intricate market. Called the “craftsmen” of the aviary, fowlers were a necessary part of proper bird care and management.1 An exception, chickens, the first animal to be widely cultivated at the villa, did not require the expertise of fowlers.2 Therefore, chickens could still be bred according to the earlier of two noted states of bird domestication at the villa: “…the earlier, which the frugality of the ancients observed, and the latter, which modern luxury [had] now added.”3

It is then between the chicken and the peafowl that villa farming strayed from Roman tradition and the nobility of a simple life. Where hens were raised in barns “on the ground,” luxury birds, including pigeon and geese, were raised in elevated “cotes” or “on the roof of the villa.”4 Furthermore, separate aviaries could be built to accommodate larger populations of “villa-feeding” luxury birds.5

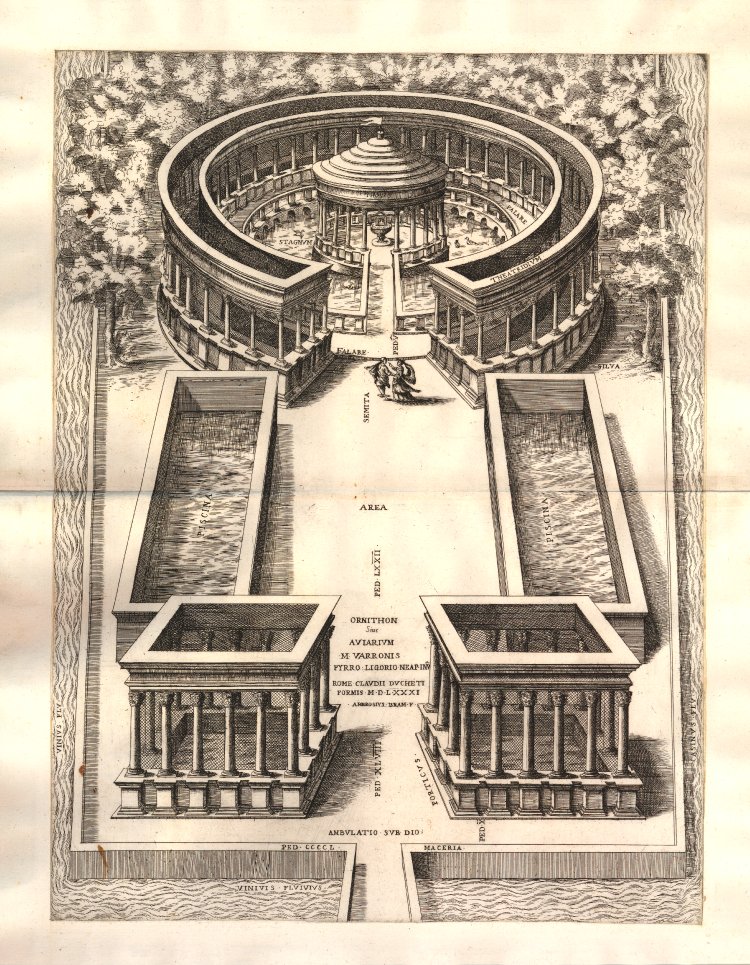

Profit-geared ornithones could be “domed” and netted, housing “several thousand” birds at a time.6 And still, an important aspect of enclosure building was proportional size of enclosure relative to number of birds and attuned to type of bird.7 Fresh active water would flow through interior pools to avoid the odors that results from stagnation.8 Other characteristics of a successful ornithone included a small entrance and minimal windows, to keep the animals from developing depression at the sight of nature, outside.9 The structure was constructed from plaster, to deter entrance by vermin and decrease entering light.10 “Cakes” of figs and spelt would be placed along the ground of the enclosure, to which the birds would flock to from raised perching rods.11 When the time came to prepare birds for sale, more cakes were given to the birds of interest, after which they were sorted into “seclustoriums,” or small branched coops, and butchered for mass sale. 12

Up to five thousand individuals could inhabit peristerons or peristerotrophions, which share a purpose and general architecture with ornithones. Similarly, the peristeron was a large vaulted building with a single narrow passage, the walls similarly plastered so that no vermin may enter the building and harm the breeding pigeons and offspring. The difference, however, between these buildings was in the amount of entering light. Punic style or wide latticed windows allowed for a great deal of light compared with ornithone interiors for increasing breeding and fitness of the breeding pairs. 13

The mixing of different bird species was also considered. Merula further explains as “[wild] pigeons fly into the villa” that multiple species of pigeon are often placed into a “dove-cote.” These birds are predetermined for cohabitation based on behavior-type and perhaps what could be described as differing ecological niches. For example, Merula states where one type of pigeon is shy and free-flying, the other, domesticated, is “content with the food from the house,” and perhaps furthermore, at ease with human handling. The ecosystem of these two birds could then produce a “hybrid species for profit. 14 The hybrid species between wild rock-dove and white domestic dove were bred in peristeron or peristerotrophion.15

Round nests were constructed for each breeding pair within rows and on top of each other to the ceiling. 16 Ill birds would have been tended to. 17 Brooding birds would be allowed to leave the enclosure, to expose these birds to healthy nutrition and fresh air. This was allowed, as animals under ownership were still considered one’s property even if they escaped beyond the owner’s property, as long as the animal had and pursued its intention of returning eventually.18 These ideals were guided by an understanding that some animals are naturally “wild,” and cannot be domesticated.19 Similarly, by allowing these birds to come and go, any predators in the area could be killed – using the knowledge of the predators that prey are in the area, pigeon-keepers could bate the predator with a tied-up animal covered with lime, and thereafter capture or kill the predator. 20

Much like with birds brought up in ornithones, for profit birds could be fattened for a higher selling price by “shutting them up,” perhaps by restricting movement by breaking their legs, or in other ways removing all stimuli except for food. These birds could be “…stuff[ed]…with white bread which has been chewed, twice…[or] three times [a day].”21 However, a change of fate could be had if a bred bird was “handsome, of good color, sound, and of good breed,” with the birds selling for use as breeders or to be kept for pleasure.22  And still, aviaries were kept for both profit and pleasure.23 Merula responds to an inquiry about fieldfare cultivation in stating that various villa birds (“ornithon”) have different purposes. Though perhaps most are bred for monetary gain, others are “merely for pleasure,” as evident with Varro’s elaborate aviary near Casinum.24 It seems, according to Pica, that those who owned dove-cotes tended to also have pigeon-houses, with equipment costing more than one hundred thousand sesterces.25 This sentence highlights the expense that it was to breed and own aviaries, being a huge luxury even amongst the elite. Varro’s aviary was had an area of forty-eight feet by seventy-two feet.26 The entrance was framed by colonnades and dwarf trees, covered by a “net of hemp.”27 And yet, Lucullus attempted to combine purposes for his aviary, in which exotic birds were both kept and consumed within the aviary. And yet, Varro notes that Lucullus encountered problems of maintaining an appetite while surrounded by large quantities of “bird droppings.”28

And still, aviaries were kept for both profit and pleasure.23 Merula responds to an inquiry about fieldfare cultivation in stating that various villa birds (“ornithon”) have different purposes. Though perhaps most are bred for monetary gain, others are “merely for pleasure,” as evident with Varro’s elaborate aviary near Casinum.24 It seems, according to Pica, that those who owned dove-cotes tended to also have pigeon-houses, with equipment costing more than one hundred thousand sesterces.25 This sentence highlights the expense that it was to breed and own aviaries, being a huge luxury even amongst the elite. Varro’s aviary was had an area of forty-eight feet by seventy-two feet.26 The entrance was framed by colonnades and dwarf trees, covered by a “net of hemp.”27 And yet, Lucullus attempted to combine purposes for his aviary, in which exotic birds were both kept and consumed within the aviary. And yet, Varro notes that Lucullus encountered problems of maintaining an appetite while surrounded by large quantities of “bird droppings.”28

- Varro, Marcus Terentius. “On Agriculture: Book III.” De Re Rustica. Loeb Classical Library, 1934: 441. ↵

- Varro, Marcus Terentius. “On Agriculture: Book III.” De Re Rustica. Loeb Classical Library, 1934: 443. ↵

- Varro, Marcus Terentius. “On Agriculture: Book III.” De Re Rustica. Loeb Classical Library, 1934: 443. ↵

- Varro, Marcus Terentius. “On Agriculture: Book III.” De Re Rustica. Loeb Classical Library, 1934: 443. ↵

- Varro, Marcus Terentius. “On Agriculture: Book III.” De Re Rustica. Loeb Classical Library, 1934: 443. ↵

- Varro, Marcus Terentius. “On Agriculture: Book III.” De Re Rustica. Loeb Classical Library, 1934: 447. ↵

- Varro, Marcus Terentius. “On Agriculture: Book III.” De Re Rustica. Loeb Classical Library, 1934: 471. ↵

- Varro, Marcus Terentius. “On Agriculture: Book III.” De Re Rustica. Loeb Classical Library, 1934: 449. ↵

- Varro, Marcus Terentius. “On Agriculture: Book III.” De Re Rustica. Loeb Classical Library, 1934: 449. ↵

- Varro, Marcus Terentius. “On Agriculture: Book III.” De Re Rustica. Loeb Classical Library, 1934: 449. ↵

- Varro, Marcus Terentius. “On Agriculture: Book III.” De Re Rustica. Loeb Classical Library, 1934: 449. ↵

- Varro, Marcus Terentius. “On Agriculture: Book III.” De Re Rustica. Loeb Classical Library, 1934: 450. ↵

- Varro, Marcus Terentius. “On Agriculture: Book III.” De Re Rustica. Loeb Classical Library, 1934: 450. ↵

- Varro, Marcus Terentius. “On Agriculture: Book III.” De Re Rustica. Loeb Classical Library, 1934: 463. ↵

- Varro, Marcus Terentius. “On Agriculture: Book III.” De Re Rustica. Loeb Classical Library, 1934: 463. ↵

- Varro, Marcus Terentius. “On Agriculture: Book III.” De Re Rustica. Loeb Classical Library, 1934: 465. ↵

- Varro, Marcus Terentius. “On Agriculture: Book III.” De Re Rustica. Loeb Classical Library, 1934: 465. ↵

- Green, C.M.C. “Free as a Bird: Varro de re Rustica 3.” The American Journal of Philology, 118, no.3 (Autumn 1997): 437. ↵

- Green, C.M.C. “Free as a Bird: Varro de re Rustica 3.” The American Journal of Philology, 118, no.3 (Autumn 1997): 438. ↵

- Varro, Marcus Terentius. “On Agriculture: Book III.” De Re Rustica. Loeb Classical Library, 1934: 467. ↵

- Varro, Marcus Terentius. “On Agriculture: Book III.” De Re Rustica. Loeb Classical Library, 1934: 469. ↵

- Varro, Marcus Terentius. “On Agriculture: Book III.” De Re Rustica. Loeb Classical Library, 1934: 469. ↵

- Varro, Marcus Terentius. “On Agriculture: Book III.” De Re Rustica. Loeb Classical Library, 1934: 441. ↵

- Varro, Marcus Terentius. “On Agriculture: Book III.” De Re Rustica. Loeb Classical Library, 1934: 447. ↵

- Varro, Marcus Terentius. “On Agriculture: Book III.” De Re Rustica. Loeb Classical Library, 1934: 469. ↵

- Varro, Marcus Terentius. “On Agriculture: Book III.” De Re Rustica. Loeb Classical Library, 1934: 453. ↵

- Varro, Marcus Terentius. “On Agriculture: Book III.” De Re Rustica. Loeb Classical Library, 1934: 455. ↵

- Green, C.M.C. “Free as a Bird: Varro de re Rustica 3.” The American Journal of Philology, 118, no.3 (Autumn 1997): 441-442. ↵