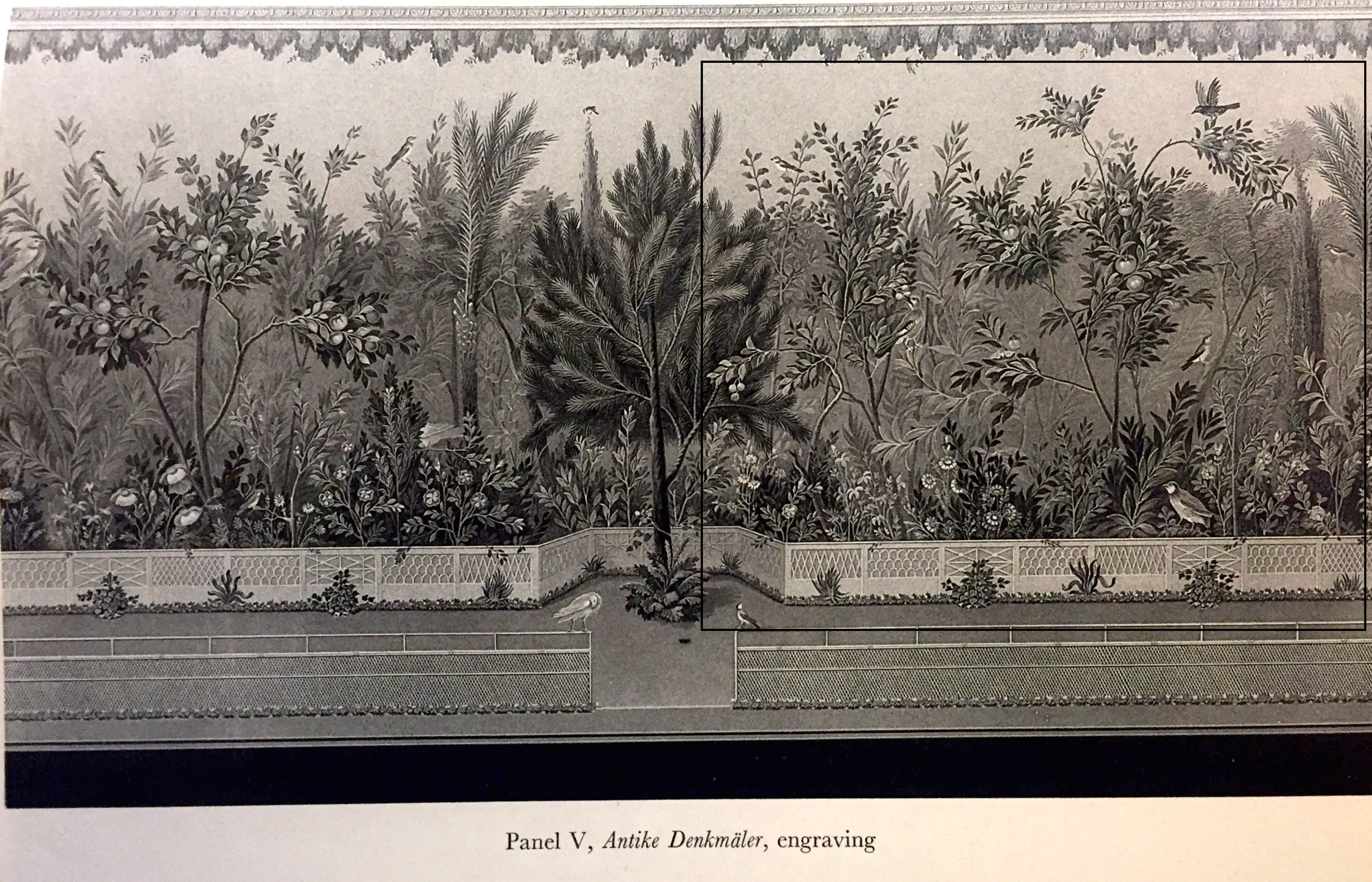

Livia’s garden wall paintings, consist of “hyper-realistic” depictions of the synchronized blooming of flora, despite these plants having different blooming times during the year.1 In this way, many of the plants, and perhaps the birds, “must” be based on sketches.2 This artistic strategy creates an eternal and unchanging image of Spring and Summer “beyond nature” and time.3 All identifications from Gabriel and Jashemski:

The blackbird would have been a year-round resident of the gardens in southern Italy.4 Similarly, the Jay and Black-eared wheatear would have inhabited southern Europe in the Summer, in wooded areas in the hills or flatlands.5 Redstarts would pursue gardens and woodland in Campania during the Summer for breeding.6

[slideshow_deploy id=’172′]

Along the bottom gate of the fresco is a pheasant or a partridge. Again, pheasants were easy to keep in captivity and though they originate from the Caucasus, their entry into Europe was noted by Aristophanes in his Birds.7 Other sources state that the pheasant was “imported from Colchis, the land of the River Phasis…[and] had been known as rarities in Greece since the fifth century.”8 It is possible that the bird shown in Rome in A.D. 47 or 48 as a phoenix was a golden pheasant.9 Furthermore, if a partridge, this bird would have been a common species in Rome as a domestic bird, similar in function to the pheasant and quail.10

In conclusion, both analyzed scenes are plausible based on the migratory patterns of these bird species, with the exception of the thrush. The only questionable factor, therefore, is whether all these birds would exist in the garden at the same time, and with what frequency. Knowing that these species prefer a wide-range of environments, I find it unlikely that all depicted birds would exist often within the garden unless artificially introduced, if kept in aviaries or bird cages at the villa.

[slideshow_deploy id=’154′]

- Gabriel, Mabel. M. Livia’s Garden Room at Prima Porta. Washington Square, NY: New York University Press, 1955: 11. ↵

- Gabriel, Mabel. M. Livia’s Garden Room at Prima Porta. Washington Square, NY: New York University Press, 1955: 11. ↵

- Jones, Frederick M.A. “The Caged Bird in Roman Life and Poetry; Metaphor, Cognition, and Value.” Syllecta Classica, 24 (2013): 113. ↵

- Jashemski, Wilheima. “Birds: Evidence from wall paintings, mosaics, sculpture, skeletal remains, and ancient authors.” The Natural History of Pompeii, 357-400. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2002: 398. ↵

- Jashemski, Wilheima. “Birds: Evidence from wall paintings, mosaics, sculpture, skeletal remains, and ancient authors.” The Natural History of Pompeii, 357-400. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2002: 385. ↵

- Jashemski, Wilheima. “Birds: Evidence from wall paintings, mosaics, sculpture, skeletal remains, and ancient authors.” The Natural History of Pompeii, 357-400. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2002: 390. ↵

- Jashemski, Wilheima. “Birds: Evidence from wall paintings, mosaics, sculpture, skeletal remains, and ancient authors.” The Natural History of Pompeii, 357-400. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2002: 390. ↵

- Jennison, George. “Amateur’s Menagerie. Birds.” Animals for Show and Pleasure in Ancient Rome. Pennsylvania, US: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005: 109. ↵

- Jennison, George. “Amateur’s Menagerie. Birds.” Animals for Show and Pleasure in Ancient Rome. Pennsylvania, US: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005: 109. ↵

- Jashemski, Wilheima. “Birds: Evidence from wall paintings, mosaics, sculpture, skeletal remains, and ancient authors.” The Natural History of Pompeii, 357-400. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2002: 376. ↵