Now that you are familiar with the story, we can discuss how and more importantly why Alcestis is shown on sarcophagi as well as in a theatrical and lyrical format. Unlike the other two myths being examined, this is the only one in which the central character fully returns from the dead to live out the duration of her life. This is a true rebirth for Alcestis, even after showing her valor, and a lesson to Admetus and all those looking on not to cheat death. Yes, these themes play themselves out in the story but there is a less thrilling though more compelling argument as to why Alcestis was so frequently shown on sarcophagi.

Through Alcestis’ sacrifice for her husband, she had set an example for her all women who either hear or see this narrative represented. Thus, her story became very popular amongst people who commission sarcophagi as the model of a noble and virtuous wife 1. When couples purchased this style of sarcophagus, their veristic portraits were typically inserted onto the faces of Alcestis and Admetus 2. This was particularly true if the husband commissioned it for him and his wife after her passing, honoring her posthumously. For the sarcophagus of Alcestis I’m honing in on, this appears to be the case.

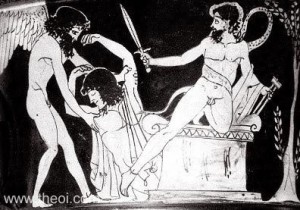

Here you can see that the composition is clear as to which scenes are being depicted so long as you know the story. It is read left to right, beginning with Apollo, shown nude and recognizable by his bow, and Admetus discussing his fate. The second scene focuses on Alcestis on her deathbed, surrounded by Apollo, Admetus, and their children. Here is where the portraits of the owners is the most conspicuous. The third scene shows a nude Hercules arriving on the scene, wielding his signature club and shaking hands with Admetus. Between the two is a small cave with Cerberus, the Underworld guard dog, which insinuates the agreement the two men are in the process of making. A youthful though veiled Alcestis stands behind Hercules, turning her back on Proserpina and Pluto, both symbolizing her escape from death’s clutches. This is one of my favorite sarcophagi in all of Roman art and I wish I had pursued a further identification of this particular work in comparison with other representations of Alcestis in stone.

While the sarcophagi were popularized to honor wives for fidelity, Euripides popularized this narrative in his play for another reason. As opposed to the visual interpretations in stone, Alcestis was not the main character in the play but rather Admetus. Despite being the title character, Alcestis functioned more as a plot device and a motivation for conflict rather than the deep and intricate symbol she is everywhere else in her representation. It’s tragic that Alcestis is dying but it also contains elements of a classical comedy. This contorted juxtaposition of the two distinct genres makes this play innovative for its time 3.

- Stine Birk, Depicting the Dead: Self-Representation and Commemoration on Roman Sarcophagi with Portraits (Aarhus: Aarhus University Press, 2013), 135. ↵

- Stine Birk, Depicting the Dead: Self-Representation and Commemoration on Roman Sarcophagi with Portraits (Aarhus: Aarhus University Press, 2013), 98. ↵

- Leo C. Curran, “Propertius 4.11: Greek Heroines and Death,” Classical Philology 63, no. 2 (1968): 134. ↵