Now that you are familiar with the story, we can discuss how and more importantly why Eurydice is shown only in music, opera, and theater and not on sarcophagi. When I embarked on this project, I struggled with the fact that there were hardly any ancient sarcophagi depictions of the Orpheus and Eurydice myth. There are plenty of small devotional tablets but little in the ways of funerary arts. However, reflecting upon the nature of the story, it makes perfect sense. Once again, the thematic elements of the story explicitly lend this narrative to a specific representative medium, the most fitting being song.

First and most obviously, this story revolves around a song or a series of songs as Orpheus recounts the manner in which Eurydice had died. These lyrical episodes are vital to the plot and the entirety of the story revolves around music. It comes as no surprise, then, that this myth is often represented in music. Why, then, is theater a conducive medium for this story? In Greco-Roman times, theater had elements of music in it, as well. Additionally, this story has a lot of emotion packed into it. That is not to say that the Proserpina and Alcestis myths lack emotion, by any means. This is one of the only times in mythology that cold, hard, Pluto is seen to be moved by love willingly (he is moved to lust by Cupid’s arrow in the Proserpina narrative). A visual and therefore silent representation of this story would not properly do the narrative justice.

Regardless of how effective music and theater are, why are there no sarcophagi that show the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice? Most likely, it is because unlike Alcestis and Proserpina, Eurydice never returns from the Underworld and remains dead. This message is a lot less comforting to mourners if they were to see these scenes of failure on the side of a coffin with their young son or daughter lying in it. There is one surviving example of a coffin with Orpheus alone on it, however.

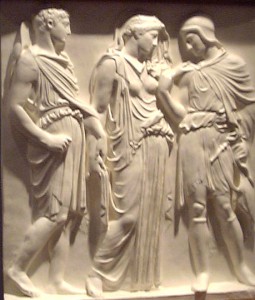

While the presence of a sarcophagus featuring Orpheus is rare, imagery of him is not. There are a plethora of vases and tile floor mosaics that depict him playing his lyre in a natural setting, alluding either to the beginning of the tale when he was happy or to the end after he lost the life of Eurydice the second time. While Orpheus is featured heavily, Eurydice is nowhere to be seen. This goes back to my statement in the introduction about the Roman perception of life. These two art forms are famously associated with pleasure. These vases would have contained wine or another luxury good while the floor mosaics decorated dining rooms and common rooms for entertaining guests. I only encountered one mosaic example depicting both characters, and even here, Eurydice is shown as something to be recovered or won. She is not necessarily a person, but rather an object that is found.

When enjoying in the bounties of the mortal realm, nobody wants to be reminded of their mortality. They simply want to indulge themselves and experience a worldly etherealness often associated with inebriation. After all, Orpheus is referred to as a god of ecstatic rites, essentially known for his lusty music 1. For this reason, Orpheus is shown alone, entertaining himself and those supposedly surrounding himself in a picturesque naturalistic setting.

- Anne Baring and Jules Cashford, The Myth of the Goddess: Evolution of an Image (New York: Penguin Books, 1993), 408. ↵