The Missionary Collection

One of the earliest and most curious sectors of Mount

Holyoke’s collection comprises a few hundred

items—many of them quite humble—that were sent

back to South Hadley by intrepid graduates of the

Mount Holyoke Seminary for Women. As teachers

and missionaries, these young women ventured to

Africa, Asia, the South Sea Islands, and elsewhere as

Mount Holyoke College Art Museum, MH 7.V.M

early as the 1830s. Even before the creation of the first art gallery in Williston Hall, there was a “museum” of sorts in the original Seminary Building in the form of a cabinet where these exotic curiosities were displayed for the edification and wonderment of the students.

Fortunately, these objects survived to become

part of the Museum collection and today form a remarkable counterpoint to historical documents in the College’s archives.

Wendy Watson, Engage

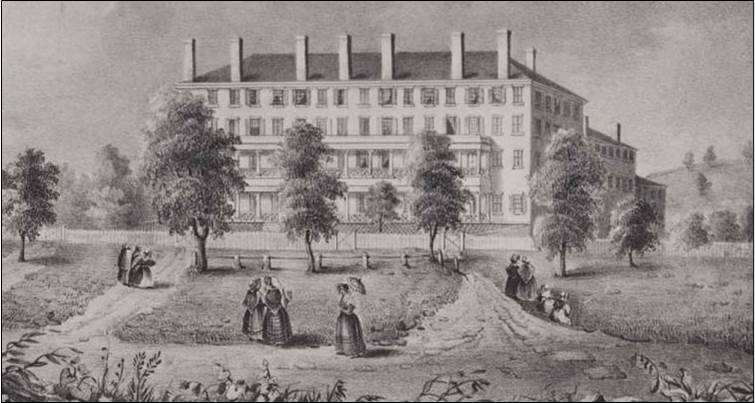

Lyman Williston Hall

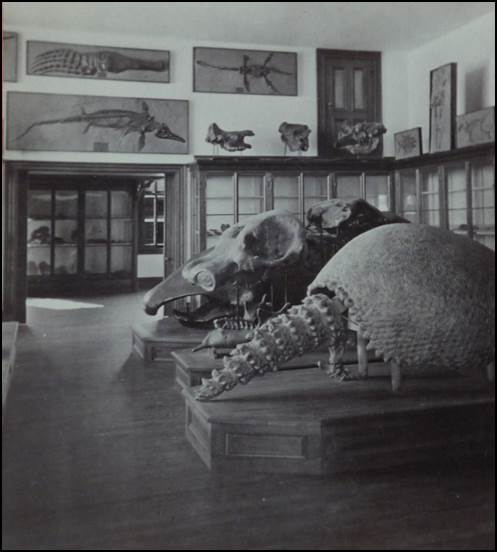

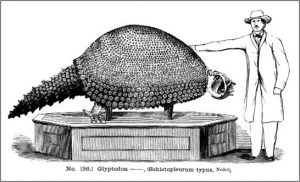

From its founding in 1876, the gallery set to bring together the riches of the natural world with artworks created by human hands. Williston Hall was indeed a marvel to behold. Four stories of cabinets of scientific wonder and state-of-the-art classrooms with speaking tubes and electric bells contained everything from an extinct flightless Moa bird and a 22 ft. geological map to a fully articulated whale skeleton. The top floor housed the art collection, with the exception of  antiquities, which were housed in the basement. The second story had the vast zoology collection and mineral cabinet including an entire set of important (and often massive) fossil casts from the Ward’s Natural Science catalogue. The first story was comprised of a lecture hall, laboratories, and the botany collection. The basement was home to the geological cabinet and one of the most impressive collections of dinosaur footprints anywhere in the United States.

antiquities, which were housed in the basement. The second story had the vast zoology collection and mineral cabinet including an entire set of important (and often massive) fossil casts from the Ward’s Natural Science catalogue. The first story was comprised of a lecture hall, laboratories, and the botany collection. The basement was home to the geological cabinet and one of the most impressive collections of dinosaur footprints anywhere in the United States.

On the afternoon of December 22, 1917, the cry went up: “Williston Hall is on fire!”[3] Although the art gallery had fortunately moved to a new space in Dwight Art Memorial Hall in 1902, the losses to the remaining campus collections were severe. Vast irreplaceable collections of mineral specimens, fossils and casts, shells, taxidermy, and more were lost. Faculty and staff braved the flames to save what they could of the building’s treasures. Abby Turner Howe recalled that “[Asa Kinney] thought of Miss [Mignon] Talbot’s fossil, her famous dinosaur, but that was inaccessible to one man though two perhaps might have dashed up through the smoke and carried the heavy thing out.”[4] Howe goes on to poetically recount the event:

We all worked in that magic place, with the gorgeous light, the fierce heat near the fire, the rain of sparks even as far as Porter—the beauty of it all a thing to remember as well as the tragedy. There were wonderful red colors in the flames, great black swirls of smoke, a few explosions when the flames reached the chemicals. And then the glow of the smoldering heaps of ruins on the clouds of silvery white smoke and steam within the half fallen walls as the fire died down.[5]

The Anthropology Museum

This story starts in the closing years of the 1920s, when Mount Holyoke Professor and Dean Harriett M. Allyn (Class of 1905) began to form a

department of anthropology. In the 1920s and 1930s there was a call to colleagues around the world for objects that charted the earliest history

of human evolution and innovation. Partially in response to the devastating fire of 1917 that destroyed the natural history collections in the

Williston Hall museum as well as in conjunction with the formation of an anthropology department, a new museum was born in Clapp: the Mount

Holyoke College Anthropology Museum.

Over the following decades, hundreds of artifacts from the dawn of humankind came to the College, including the remarkable lithics recently found in Clapp. Portions of this rare and comprehensive lithic collection were fashioned by modern humans (Homo sapiens) tens of thousands of years ago, but other tools were shaped by Homo neanderthalensis and even by the much more ancient Homo antecessor. The majority of these stone implements still retain valuable catalogue information about where they were found and the fascinating hominids that made them tens or hundreds of thousands of years ago. An analysis of the techniques used to create these stone tools offers insight into the transmission of ideas and technologies across very ancient populations. Their forms tell us about their specific functions and hint at landscapes and animals that predate modern humanity. The oldest implements in the collection were recovered from Cromer and Boscombe, England, and were chipped from flint as many as 500,000 years ago. French sites are also represented in the collection; most notably tools from La Madeleine rock shelter, the site after which the Magdalenian culture (15,000–10,000 BCE) was named and most famous for its sculptural Bison Licking Insect Bite, dating from around 20,000 years ago. The collection also includes tools from important Spanish sites like El Castillo cave and Altamira, with

valuable catalogue information about where they were found and the fascinating hominids that made them tens or hundreds of thousands of years ago. An analysis of the techniques used to create these stone tools offers insight into the transmission of ideas and technologies across very ancient populations. Their forms tell us about their specific functions and hint at landscapes and animals that predate modern humanity. The oldest implements in the collection were recovered from Cromer and Boscombe, England, and were chipped from flint as many as 500,000 years ago. French sites are also represented in the collection; most notably tools from La Madeleine rock shelter, the site after which the Magdalenian culture (15,000–10,000 BCE) was named and most famous for its sculptural Bison Licking Insect Bite, dating from around 20,000 years ago. The collection also includes tools from important Spanish sites like El Castillo cave and Altamira, with  their unforgettable red ochre animals and handprints. The College collection even has small fragments of red ochre, the pigment used in the oldest known examples of artistic expression. The collection also contains objects from East Asia and the Middle East with tools from Zarzi Cave in Iraqi Kurdistan, and Tabun Cave at Mount Carmel, Israel, where Harriett M. Allyn herself participated in excavations in 1929.

their unforgettable red ochre animals and handprints. The College collection even has small fragments of red ochre, the pigment used in the oldest known examples of artistic expression. The collection also contains objects from East Asia and the Middle East with tools from Zarzi Cave in Iraqi Kurdistan, and Tabun Cave at Mount Carmel, Israel, where Harriett M. Allyn herself participated in excavations in 1929.

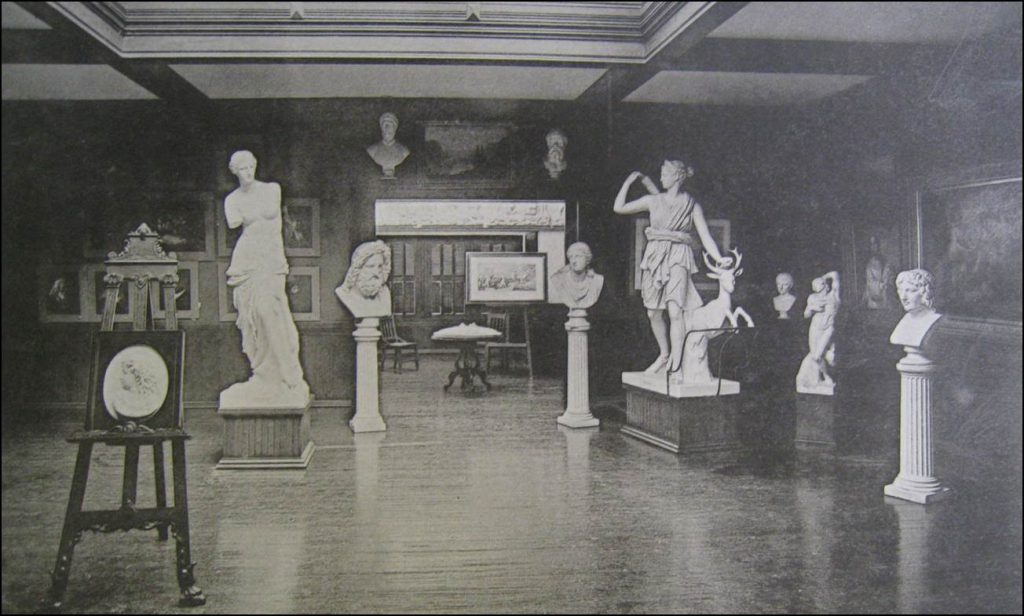

Dwight Memorial Art Building

Funds for this building came from John Dwight, a former South Hadley resident, whose first wife, Nancy Everett, had been a student at the Seminary. Mr. Dwight was persuaded to provide funds for an art building which could serve as both a memorial to the late Nancy Everett and as a suitable house for his second wife’s collection of works by the noted American illustrator Elbridge Kingsley.

Ground was broken for Dwight Art Memorial in December 1900. The building included badly needed classroom and library space; it also provided several areas for the display and storage of the art collection. A skylighted  exhibition gallery on the top floor housed the collection of paintings and framed reproductions. The entrance floor of the building contained a gallery for the display of the yet-to-be acquired collection of plaster casts, while on the floor beneath the cast gallery, space was set aside to store and display smaller items in the study collection.

exhibition gallery on the top floor housed the collection of paintings and framed reproductions. The entrance floor of the building contained a gallery for the display of the yet-to-be acquired collection of plaster casts, while on the floor beneath the cast gallery, space was set aside to store and display smaller items in the study collection.

Jean C. Harris, The Mount Holyoke College Art Museum: Handbook of the Collection, 1984

The Mary Lyon Room

For many years, a collection of objects related to the early history of Mount

Holyoke College were displayed in the Mary Lyon Room within Mary Woolley

Hall. During World War II, this space was used for volunteers knitting for the armed forces and the contents of the room were dispersed across the campus

to make room for the war effort.

Like many other objects from that collection, this basin may have belonged to the College’s founder Mary Lyon. Based on the date of manufacture, this is a possibility. The basin and a matching pitcher were part of a lusterware wash set that has molded elements recalling the Rococo style. Lustrous glazed earthenware vessels were extremely popular in Great Britain and America in the early 19th century and the technique embellished many forms and designs.

The Joseph Allen Skinner Museum

The Joseph Allen Skinner museum is a cabinet of curiosities filled with some 7,000 objects from across the world and through time. Joseph Skinner (1862-1946), a local textile industrialist, acquired and organized the eclectic collection in the 1930s and 1940s and gave it to Mount Holyoke College in 1946. The Museum also houses a piece of Skinner’s own story, told through materials and memorabilia of the Skinner family. Growing up during the late

nineteenth century in the industrial towns of western Massachusetts, Skinner’s fascination with the region’s natural history fostered his strong and lasting desire to collect. Over time, he pursued his education, traveled in Europe, and established himself in his family’s silk business. With great success came significant financial rewards that he used to invest in properties, to build and promote Mount Holyoke College, and to acquire objects.

Skinner’s plans to establish a museum of his own materialized in the late 1920s and 1930s. During this time, he salvaged an early nineteenth-century meetinghouse and other structures from the small town of Prescott, Massachusetts. The buildings were slated for inundation during the construction of the Quabbin Reservoir, which was intended to supply Boston’s

drinking water. Piece by piece the structures were dismantled and then reconstructed on Skinner’s property in South Hadley, where he positioned them to form an idealized New England village. Skinner’s “town” included a meetinghouse, a schoolhouse, and two carriage houses bordering a central common. With these buildings in place, and his collections put on display

reconstructed on Skinner’s property in South Hadley, where he positioned them to form an idealized New England village. Skinner’s “town” included a meetinghouse, a schoolhouse, and two carriage houses bordering a central common. With these buildings in place, and his collections put on display

within, the Joseph Allen Skinner Museum was established and opened to the public in 1932.

From that time until 1946, when he donated the property, buildings, and collections to the College, Skinner continued to accumulate, catalogue, and arrange objects for his Museum. Many were purchased from auctions, antique dealers, and shops; others were simply found objects or pieces acquired during his journeys. Skinner family members and local history enthusiasts donated objects to the Museum as well. The collection that evolved offers a glimpse  into Skinner’s views on the importance of the past, the progression of technological innovation, and his belief that objects could be used to inform and amaze the public. While each of the 7,000 objects in the collection tells an important individual story, it is the Museum as a whole—Joseph Skinner’s narrative, created when he brought these disparate objects together to live forever in a small New England village of his own construction—that holds fascinating implications for future research.

into Skinner’s views on the importance of the past, the progression of technological innovation, and his belief that objects could be used to inform and amaze the public. While each of the 7,000 objects in the collection tells an important individual story, it is the Museum as a whole—Joseph Skinner’s narrative, created when he brought these disparate objects together to live forever in a small New England village of his own construction—that holds fascinating implications for future research.