Caroline Louise Ransom Williams should be remembered as the Queen of Egyptology for many reasons. During her lifetime, she broke barriers in education and paved the way for women to study Egyptology. Her personal letters tell how much she valued her research and contributed back to her alma mater.

Breaking Barriers

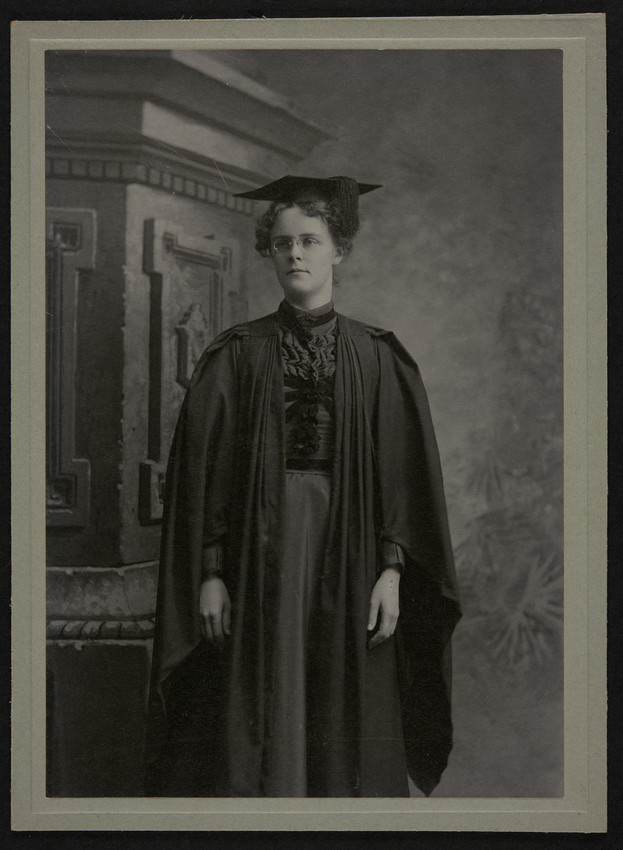

Ransom Williams began her life in Toledo, Ohio. The daughter of John and Ella Randolph Ransom, she was born on February 24,1872. Very bright, she attended the local Erie College, and eventually her aunt Professor Louise Fitz Randolph persuaded her parents to send her to Massachusetts to complete her education at the more prestigious Mount Holyoke College. Ransom Williams graduated in 1896, only a few years after the Seminary had become a College. It was a time of major transition for the school, and her class was the last to study in Skinner Hall, which burned down the following September. Upon graduation, Fitz Randolph invited Ransom to accompany her to Europe. It was in Egypt that she discovered her life’s passion: Egyptology. From 1898 to1899, Ransom Williams decided to pursue a degree in Egyptology under the great professor James Henry Breasted at the University of Chicago. She obtained a degree in both Egyptology and Archaeology at Chicago and from 1900 until 1903, went to Berlin to study with Professor Adolf Erman, She was one of the first females in Continental Europe to study Egyptology at a university.

Starting her life’s career, Ransom Williams worked as an assistant at the Berlin Museum in the Egyptian Department. Following that, in 1905, she became the first woman to earn a PhD. in Egyptology making her “America’s first professionally trained female Egyptologist,” as her biographer, Barbara Lesko. That same year, she took on a position as an assistant professor in the Department of Archaeology and Art at Bryn Mawr College and remained there until 1910, also becoming chair of the department. In these years, Ransom Williams was also appointed assistant curator in the Egyptian Art Department at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. [To understand the significance of her role, one should recognize that this was a key moment in the development of American public museums. Industrialist and philanthropist John Pierpont Morgan donated generously to the museum stating that he thought the Metropolitan Museum should be “the best in America.”

Published Books

Ransom Williams published several books throughout her career. She was the first female with an article in the German Archaeological Year Book and contributed to the Journal of American Archaeology and other publications. In 1911, Ransom Williams co-authored the Handbook of the Egyptian Rooms at the Metropolitan Museum. She deciphered inscriptions and catalogued the collections from the Egypt Exploration Fund which held an annual exhibition of its legally acquired artifacts with the intention of distributing them to various institutions. Keeping her close ties to the Metropolitan Museum, she was given permission to return to Germany and continue working with Professor Erman, where she found time to send back information on procuring plaster casts to Fitz Randolph. In Mount Holyoke’s 75th anniversary year, Ransom Williams was awarded an honorary Doctor of Literature degree. In 1916, she accepted the marriage proposal of a real estate developer named Grant Williams and returned to Toledo. Settled in Ohio, from 1916 to 1917, she worked at the Cleveland Museum of Art and the Minneapolis Institute of Arts and at the Toledo Museum of Art.

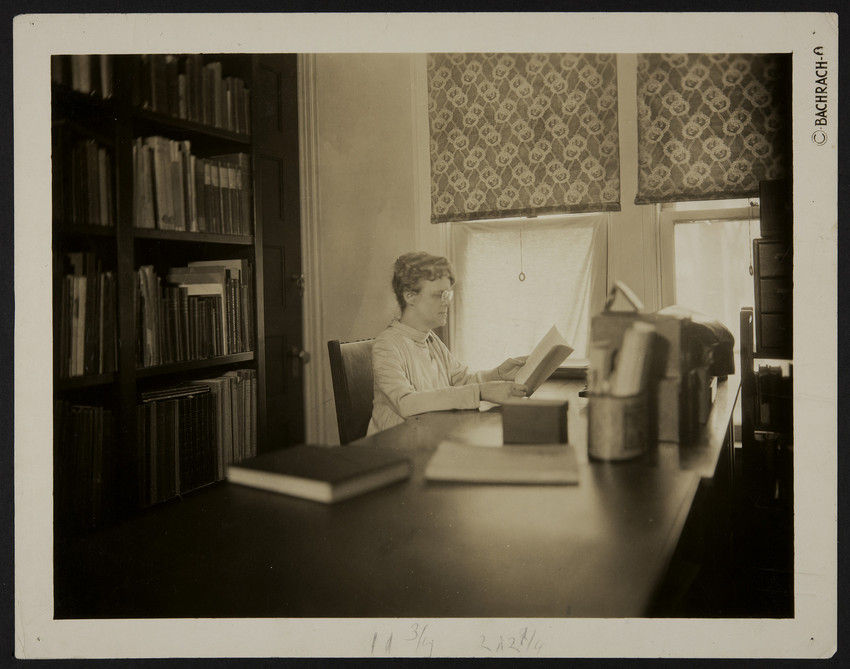

In 1917, Ransom Williams became curator of the Egyptian Collection at the New York Historical Society, where she prepared a 250 page scientific catalogue of more than four thousand Egyptian objects in the Abbott Collection, published in 1924 as Gold and Silver Jewelry and Related Objects.. Her research was so refined that Ransom Williams used a microscope to study the methods of ancient craftsmen and detect forgeries. She also contributed to the standard work Aegyptisches Wörterbuch, the Berlin Dictionary of Hieroglyphic Vocabulary by Professor Erdman et. al., which first appeared in 1925 and notes personal gifts from Breasted and Ransom Williams. After support from the German government was lost in World War I, a grant from American philanthropist John D. Rockefeller, Jr. ensured the publication of this valuable book.

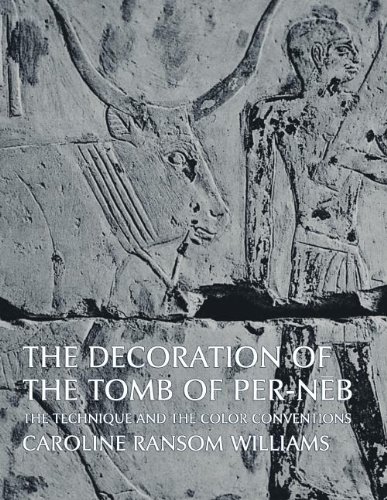

Later in life, Ransom Williams was recruited by Professor Breasted of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago to be a member of his Epigraphic Survey team in Egypt. In 1926 and 1927, she worked on site as an epigrapher at the Temple of Ramses III. And in 1927 and 1928, she taught Egyptian art and language at the University of Michigan . It was the first time the University offered Egyptology, and Ransom Williams again played a crucial role. In 1929, she became president of the Midwest Branch of the American Oriental Society, the first female to ever hold the office. Throughout all these years, she maintained a lively connection to The Metropolitan Museum, which published her Decorations of the Tomb of Per-Neb in 1932. Tireless in her work on Egyptian Art across the country, she also spent time studying and cataloguing small Egyptian collections at the Cleveland Museum, the Minneapolis Institute of Art, and the Toledo Museum of Art, where she later became honorary curator.

She stayed in Toledo and commuted to New York for seven years. Eventually, the collection was purchased by the New York Historical Society and transferred to The Brooklyn Museum.

Having no children, Ransom Williams was able to continue her work on the Epigraphic Survey in Egypt, which meant spending half a year in Luxor living and working in a mud brick facility. Unlike subsequent directors, Professor Breasted apparently had no reservations about including a woman as a member of his staff. In fact, he recorded his “profound appreciation that Dr. Williams worked an entire season at Medinet Habu out of pure interest in the project and with almost no remuneration,” It would be many years before another woman was invited to be a member of the Epigraphic Survey. Clearly, Ransom Williams stood apart for her dedication and capabilities, researching at Medinet Habu, the Temple of Ramesses III, and on the Coffin Texts at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. It is hard to imagine that she had any time or energy left, but Ransom Williams also served as a member of the Archaeological Institute of America and was a corresponding member of the German Archaeological Institute. An international scholar of note, in 1937 she was awarded an honorary degree from the University of Toledo.

Donations to Mount Holyoke College

Little is know about Ransom Williams’ personal life. Her husband died in 1942 after a long illness at the age of 77. Shortly thereafter, in 1943, she donated a small collection of Egyptian antiquities to Mount Holyoke College. As a widow she remained in Toledo for ten years and taught at the University of Michigan until she died in 1952, just short of her 80th birthday.

Giving back: Beetles in the Mount Holyoke College Art Museum

Caroline Ransom Williams is known for the many gifts she donated to Mount Holyoke College. Even though she was an Egyptologist, most of the items are actually Greek and Roman and quite significant. This brings us back to the intimate connection with her aunt, Louise Fitz Randolph.

The Egyptian scarabs, some currently on view in the museum, are among the most beautiful objects Ransom Williams donated to Mount Holyoke. Depending on their period and inscriptions, the native dung beetles of Egypt can have very different meanings. There are ornamental scarabs, heart scarabs, winged scarabs, scarabs with the name of a king or queen, marriage scarabs, lion hunt scarabs, commemorative scarabs, scarabs with good wishes and mottos, scarabs with symbols of unknown meaning, and scarabs decorated with figures and animals.

Egyptians worshiped animals and such tokens were affordable, popular, and often worn as charms to protect from evil. Most are made of steatite coated with a glazed color and are particularly important to archaeologists and historians because their inscriptions say much about what was meaningful to the culture during that time.

The first Egyptian scarab documented from Ransom Williams’ collection is from the New Kingdom period 1504-1450 BCE (illustrated). On the underside of the dung beetle is a design of a striding horse, symbolizing the King. Above the horse’s back, is an inscription. The oval is called a horizontal cartouche with a line at one end indicating that it is a royal name, “Menkheperre.” This scarab also has the hieroglyph “nefer” meaning good or beautiful. Lines on the horse are supposed to represent trappings.

Another scarab of 1570-1293 BCE (New Kingdom, Dynasty 18) apparently was meant to be worn as jewelry, one can tell by the holes on either side of it. In general, New Kingdom scarabs like this one were often named after gods, and were combined with short prayers or mottos. Made of buff-colored steatite, underneath this scarab, a god kneels and faces right,holding a notched papyrus stalk. The design symbolizes a wish for longevity. The notched stalk indicates years and the god, Heh, was the sign for “a million.” Although this was a gift from Ransom Williams, like others, it belongs to the collection of Professor Louise Fitz Randolph who predeceased her niece in 1932.

Conclusion

Ransom Williams is “remembered by her College for her devotion to ‘family, church, each Alma Mater, to friends in all walks of life at home and abroad.’ ‘Erudite in her field, she was also warmly interested in contemporary life and in people. Her devotion to Mount Holyoke was evidenced in gifts to the library and to Dwight Art Memorial, and more substantially in her renunciation, in 1945, of the quarterly annuity assigned to her for life by her aunt Louise Fitz-Randolph, ‘so that the Louise Fitz-Randolph Fellowship in Art might operate immediately.” Ransom Williams paved the way for women in Egyptology. She was also not one waste time. As one can tell by a Mount Holyoke questionnaire in which she states, “This bores me to extinction.” She dedicated her life to education, studying at some of the top universities. These accomplishments are only a few of her many achievements. “In her thought, in her conversation and actions, she expressed continually a living interest in the College.” Ransom Williams’ spirit will live on and her achievement never be forgotten.

[slideshow_deploy id=’905′]

Timeline of Caroline Ransom Williams

1872

Born in Toledo, Ohio

1896

Graduates from Mount Holyoke College

1898-1900

Goes to the University of Chicago and receives an AM in Classical Archaeology and Egyptology

1903

Works for the Egyptian Department at the Berlin Museum

1905

Awarded a Ph.D. from the University of Chicago in Egyptology, making her the first woman to receive an advanced degree in this discipline

Becomes an assistant professor in the Department of Archaeology and Art at Bryn Mawr College – later becoming chair of the department

1910

Becomes Assistant Curator of the Department of Egyptian Art of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York

1911

Co-authors the Handbook of the Egyptian Rooms for the Metropolitan Museum of Art

1916

Returns to Toledo, Ohio, and accepts proposal from Grant Williams, a real estate developer

1916-1917

Works at the Cleveland Museum of Art and the Minneapolis Institute of Arts

Offered a curatorship of the Egyptian Collection of the New York Historical Society

1924

Published Gold and Silver Jewelry and Related Objects

1926-1927

Works as an epigrapher in Egypt for the Oriental Institute at the Temple of Ramses III

1927-1928

Teaches at the University of Michigan in Egyptian Art and in Middle Egyptian phase of the ancient language

1932

The Metropolitan Museum of Art publishes her Decorations of the Tomb of Per-Neb

1935-36

Works in Egypt, helping with the translation of Coffin Texts at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo

1942

Grant Williams dies at 77 years old

1952

Ransom Williams dies approaching her 80th birthday

Work Cited

ASCMHC, Mount Holyoke Alumnae Quarterly, Vol. 72, No. 1, 49.

ASCMHC, “Dr.Williams Woman Distinguished As Egyptologist,” Toledo Blade, February 2, 1952.

ASCMHC, Directory of American Scholars: A Biographical Directory, Lancaster: 1942.

ASCMHC, Grant Williams, Toledo Blade, December 25, 1942.

ASCMHC, Mount Holyoke College One Hundred Year Directory Alumni Biographical Record, October 29, 1936.

Charles Breasted, Pioneer to the Past: The Story of James Henry Breasted, Archaeologist, New York: Charles Scribners, 1945.

James H. Breasted, The Oriental Institute, (The University of Chicago Survey, Vol. XII) Chicago: 1933.

Lesko, Barbara S. “Caroline Louise Ransom Williams, 1872-1952.” Breaking Ground: Women in Old World Archaeology. Web. 29 Nov. 2016.

Written by Whitney L. Schott, Class of 2017