Edith Hall Dohan was a female archaeologist and fearless educator. She dedicated her life to the study of Greek and Etruscan art; ultimately making discoveries that led to a better understanding of Minoan pottery and Italic tomb-groups. Moreover, Hall was a loving and kindhearted person who left a positive impression on nearly everyone she met. And while she only taught Classical Archaeology and Greek at Mount Holyoke for four years, her lectures were deeply appreciated and highly anticipated by students and faculty members alike. 1

Early Life and Education

Born December 31, 1877 in New Haven, Connecticut, Hall was afforded every opportunity possible to succeed academically. Her father, Ely Ransom Hall, was a graduate of Yale University. A native of Dannemora, New York, he taught mathematics at the Hopkins Grammar School before becoming principal at Woodstock Academy in 1899. 2 “During his twenty-six years in that position he pulled the school out of an economic and academic slump, turning it into one of the finest secondary schools in New England.”3 He developed a formalized four-year course of study, which expanded enrollment and he introduced extracurricular activities while building relationships between the school and the community. During his time as principal he also “…served as chorister, deacon, superintendent of the Sunday school and society’s treasurer in the Congregational Church.”4

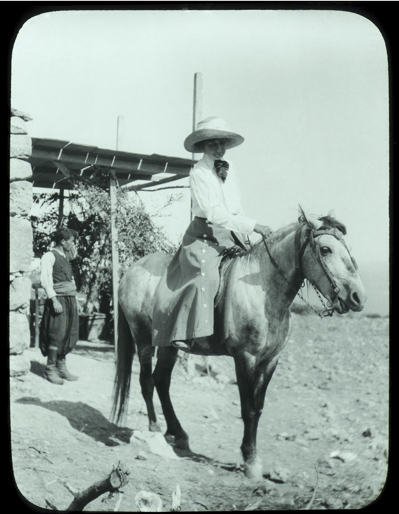

Hall’s mother, Mary Jane Smith Hall, was a native of Windsor, New York. 5 She married Ely in September 1875 6 and subsequently had three children: Edith, Anne, and Clarence. Moreover, Hall’s father was extremely strict and believed in the importance of education and “a well-founded Christian ethic”. 7 Thus, he had all of his children attend Woodstock Academy. Hall excelled at the academy. When she wasn’t developing her love of Greek, she made time for sports. She rode horses and bicycles, and played golf (which was her favorite). 8“Her niece, many years later, recalled stories of Hall pedaling furiously down the Woodstock sidewalks with her golf clubs strapped across the handlebars of her bike…as she breathlessly fought to arrive in time to tee off.”9

After high school Hall decided to attend Smith College. Most girls in her town married local farmers or businessmen after high school, but she decided to follow her dream of studying Classics. 10 Her Classics major required her to take courses in Greek, Latin, Math, Biblical Literature, English, Physiology, and Elocution. 11 And in 1899 she graduated from Smith with Honors, and returned home to teach Greek and History at Woodstock Academy. It’s important to note that her sister Anne attended Smith with her, graduating a year before her in 1898. 12 Furthermore, Hall’s employment at Woodstock Academy lasted only a year because she realized that teaching grade school was unfulfilling. 13 So she decided to begin her graduate studies.

Thus Hall entered graduate school at Bryn Mawr, studying classical archaeology. She loved her professors and fellow classmates, but worried a lot about supporting herself financially. Because her family could not help her pay her tuition, she tutored at the nearby Shipley School and chaperoned dances at the Baldwin School. 14 And the students of Bryn Mawr also assisted her. One year there was a dormitory fire, wherein Hall sounded the alarm, helped clear the building, and risked her life by going inside to retrieve another student’s thesis. The students were so stunned by her bravery that they raised thirty dollars to help Hall finish the semester and replace clothing that was lost in the fire. 15

Her Time in Athens

In 1903 Hall was awarded $500 via the Mary E. Garrett European fellowship to study at the American School of Classical Studies in Athens. She also received an additional $1,000 via the Agnes Hoppin Memorial Fellowship, which was created to “lift the restrictions on women in the study of archaeology”. 16 Unfortunately, she was the last ever Hoppin Fellow; “the fellowship was discontinued on the opinion that there was no longer a need for this type of affirmative action”. 17 Moreover, this money helped Hall become Bryn Mawr’s first fellow in Athens and the only female student at the American school that year. At the school, she studied decorative motifs on Mycenaean and Minoan pottery. She would visit museums in Greece and Crete and collect the designs she saw by drawing them in her notebooks. 18

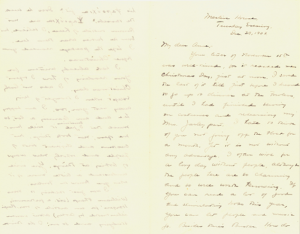

When she wasn’t studying, “she yearned to participate in the dinner conversations of her fellow male students at the school’s dining facility…”19 Unfortunately, men and women were kept separate at the school, so for the first few weeks she focused on her studies—attending lectures “ [on] Greek language and literature”. 20 During this somewhat lonely time, she met Richard Berry Seager—an associate member of the American School and a future friend and colleague. Hall mentioned his arrival in a letter home, explaining that “a Mr. Segur [sic]…is going to help Miss Boyd in Crete for a second season. He is good-looking and carefully dressed…”21 And in a December 1903 letter to her sister Anne, she discussed the pressure she felt to get married and her desire to work with Harriet Boyd.

“I was just talking to Mrs. William Sharp about women studying and so on: I do think that a girl of my age has an awfully hard course to steer, if she keeps herself scholarly for a teaching career, and womanly against the chance that she may marry. Miss Boyd is coming in February to continue her Cretan excavations. I wish she would break me in to that work and take me as an assistant in her next two or three campaigns. Don’t mention such a thing at home, for it is hardly possible. But I should like to get to work with a woman like that.” 22

And in another letter to Anne she discloses her reasons for studying archaeology.

“I suppose it all seems very specialized and unprofitable…I console myself by thinking first that when Warner [Hall’s younger brother] gets to studying ancient history, he will read in even the briefest history a very different account of the years 4000-1000 B.C. in Greece, than that which I studied, and which is still studied in schools…Secondly, I often say to myself that it must be good for me because it is so hard. Doing a piece of work which has never been done before is a long tedious task, which calls for painstaking and accuracy, and for alertness, even through all the dull places.” 23

Though as word spread that there was an American woman in town, Hall’s letter-writing and loneliness quickly ended. Visitors, like Mrs. Bosanquet (wife of the director of the British School) and Madam Sophia Schliemann (the governess to the royal children of Prince George, future king of Greece), would come to have tea with her and leave behind calling cards. 24 Eventually she became so popular that she was presented to the queen of Greece. 25

However, when Hall wasn’t socializing, she went on trips with the school. The first was a three-day journey to Delphi. The professors, the professors’ wives, and the students struggled with intense heat and hotel rooms infested with bedbugs. 26 In fact, the bedbugs were so bad that Hall would find them crawling on her gown during meals. 27 In a letter sent home, she also mentioned that it was a common occurrence to find rabbits and stray dogs near their dinner table. 28

Fieldwork: Digging on the Island of Crete

In 1904 Hall was invited to dig with Harriet Boyd in Gournia in Crete. Her primary qualification for the job was her ability to ride a horse 29, but ultimately she was chosen because Richard B. Seager recommended her and because Boyd desperately needed an assistant, as it was considered improper for a woman to live out in the field unaccompanied. 30 However, Richard Seager warned Hall of Boyd’s erratic behavior; Boyd is a “hard person to get in [sic] with…She is absent-minded and says one thing one day, and another, the next. She is, evidently sharp-tongued too.”31 Hall wasn’t worried though and that year they traveled around Crete on mules and on foot, lived in tents, and excavated Gournia. 32 They also slept in monasteries or in the homes of villagers. 33 Conditions at the excavation site were bad. In a letter Hall notes that the site, “…was in a wild and rugged district where our ponies could scarcely make their way over boulders and along dizzy ledges, and where it was difficult to find a level spot big enough to pitch my tent…”. 34

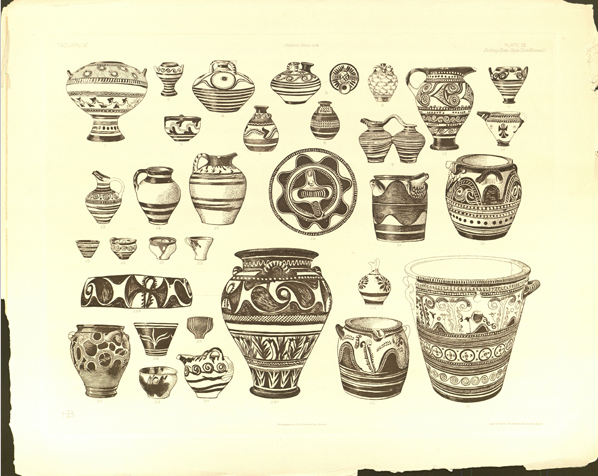

Despite terrible conditions, Hall and Boyd got along splendidly. It wasn’t uncommon for them to pass time by singing or reciting Greek poetry. 35 But more than anything, Hall’s “calm, patient, and quiet nature uniquely counterbalanced Boyd’s lively personality.”36 Hall was also willing to take on tasks that bored Boyd, like the 20,000+ pottery sherds she found and was unwilling to study. 37 Hence Hall measured, catalogued, cleaned and photographed these sherds—some of which dated from about 2,000 B.C. 38 These sherds, which turned out to be the earliest painted pottery, revealed a “new pottery series which included eight distinct styles from the Third Millennium B.C. down to the full Iron Age.” 39 Moreover ancient Gournia had no palace and was essentially home to commoners, so these finds also helped reveal clues about the lives of regular Mycenaeans. 40 And in 1905, Hall presented these finds to the International Archaeological Congress in Athens. As a consequence these objects became the first Mycenaean and pre-Mycenaean collection in the United States.

While Hall and Boyd’s working relationship was important, their relationship with the surrounding community was even more critical. If villagers felt appreciated by them, then they had a better chance of being led to more finds. 41 Since Hall was friendlier than Boyd, she engaged with the community the most. She was bridesmaid at the wedding of one of her workers 42 and was a favorite among the village children; in fact eighty years later when Hall’s grand-daughter visited Crete, one former child remembered Hall and had a picture of her pasted to his wall. 43 Hall and Boyd were also expected to be accommodating to visitors, who came to see the progress that had been made at the site. 44

However, in the spring of 1905 Hall left Athens and returned to teach at the Shipley School outside Philadelphia. And in 1906 she earned the first classical archaeology Ph.D. awarded by Bryn Mawr College for her dissertation The Decorative Art of Crete in the Bronze Age. Then in 1908 she came to Mount Holyoke College to teach Classical Archaeology and Greek. “This position required her to teach during the fall semester but allowed her to continue digging in Crete in the spring.” 45 She was an active lecturer for the college’s Archaeological Club and served on the club’s committee. In addition, that same year Hall and Boyd published their Gournia findings, which became the first monograph produced by women archaeologists. 46

Furthermore Hall continued digging in Crete on behalf of the University of Pennsylvania Museum. She took on the directorship of Vrokastro, becoming the second woman to direct an archaeological excavation on Crete and the third woman ever in Greece. Then in 1910 Hall received the opportunity to take over one of Boyd’s excavations in Crete. Boyd had retired due to marriage, so under the direction of Richard B. Seager and with funding from the Free Museum of Science and Art in Philadelphia, Hall decided to try to uncover the origins of Minoan civilization. 47 However, Seager did not really oversee her excavation, as he was suffering from a chronic illness that prevented him from being on-site. 48

Nonetheless, at Sphoungaras, Hall discovered over 150 pieces of Late Minoan pottery. And she also uncovered six unlooted Iron Age tombs, which held vases and Egyptian seal stones. 49 In 1911 she donated 26 objects to the Mount Holyoke Art museum, all of which were Greek clay (or terracotta) sherds, dating from 3300 BCE. In 1912, she left Mount Holyoke to become assistant curator and designer of the Cretan Room, at the University of Pennsylvania Museum. At the museum, she “supervised the cataloguing and rearranging of a large collection of classical antiquities; she also published articles on a great variety of archaeological material and lectured to Philadelphia schoolchildren.” 50 And in 1913 she returned to Mount Holyoke College as a guest lecturer to discuss her finds. 51

Later Years

In April of 1915 Hall announced her engagement to Joseph M. Dohan, a Philadelphia lawyer and owner of The Glen Mills Paper Company. 52 They were married on May 12, 1915 and took up residence at her Chestnut Street home, furnished with rugs and other things she purchased during her travels. 53 Together they had two children: David and Katherine. Subsequently she spent the next 15 years raising her two children, while teaching part-time at Bryn Mawr College. In 1920, she returned to the University of Pennsylvania Museum as associate curator of the Mediterranean section. She devoted most of her time to the museum’s collections, specifically their maintenance and display. Hall also created a publication on Italic Tomb Groups in the University Museum. There was a massive amount of uncatalogued Etruscan art in the museum’s storerooms (that had been excavated in 1897), so she decided to reconstruct the original tomb-groups and create an exhibition. Her work, entitled Italic Tomb-Groups in the University Museum (1942), was hailed as her greatest work and as the first attempt ever made to establish a synchronology of seventh-century Etruscan graves”. 54

Hall’s Legacy

Hall died on July 14th, 1943. She was only 65 years old, when she collapsed at her desk surrounded by artifacts that she had excavated. It happened during a heat wave, but the cause of death was atherosclerosis.

Her friends, colleagues, and students remembered her as a superb human being, “who demanded integrity in her students as in herself”. 55 She was extremely generous, having even given her salary to a younger staff member who was in need. 56

Before her death, Hall succeeded in leading her own excavation, receiving the first ever doctorate from Bryn Mawr College, and becoming an expert in Minoan and Etruscan art. She gave “stimulating and valuable” lectures at Mount Holyoke and Bryn Mawr, further proving herself to be one of the ablest young American archaeologists. 57 Moreover, her work and success is a testament to women’s colleges and their constant support of female scholars.

Timeline of Edith Hall Dohan’s Life

1877

Born December 31st in New Haven, Connecticut

1899

Graduated from Smith College with Honors

1903

Was awarded a combined $1500 from the Mary E. Garrett European fellowship and the Agnes Hoppin Memorial Fellowship, to study at the American School of Classical Studies in Athens

1904

Was invited to dig with Harriet Boyd in Gournia, in Crete

1905

Presented Mycenaean and pre-Mycenaean finds to the International Archaeological Congress in Athens

Left Athens in the spring to teach at the Shipley School outside Philadelphia

1906

Earned the first classical archaeology Ph.D. awarded by Bryn Mawr College for her dissertation The Decorative Art of Crete in the Bronze Age

1908

Came to Mount Holyoke College to teach Classical Archaeology and Greek

1910

Received the opportunity to take over one of Harriet Boyd’s excavations in Crete

1911

Donated 26 objects to the Mount Holyoke College Art museum, all of which are Greek clay (or terracotta) sherds, dating from 3300 BCE

1912

Left Mount Holyoke to become assistant curator and designer of the Cretan Room, at the University of Pennsylvania Museum

1913

Returned to Mount Holyoke as a guest lecturer

1915

Married Joseph M. Dohan

Began teaching at Bryn Mawr part-time

1916

Gave birth to her first child, David

1918

Gave birth to her second child, Katherine

1920

Returned to the University of Pennsylvania Museum as associate curator of the Mediterranean section

1942

Published her work on the University of Pennsylvania Museum’s uncatalogued Etruscan Art, Italic Tomb-Groups in the University Museum

1943

Died on July 14th at the age of 65

Works Cited

Becker, Marshall Joseph, and Phillip P. Betancourt. Richard Berry Seager: Archaeologist and Proper Gentleman. University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, 1997.

Claasen, Cheryl. Women in Archaeology. University of Pennsylvania Press, 1994.

Debnar, Paula. “Marion Blake’s Early Years: Student, Teacher, Scholar.”Musica & Sectilia (2010): 34.

“Edith Hayward Hall Dohan (1877-1943).” Breaking Ground, Breaking Tradition. Accessed October 16, 2016. http://www.brynmawr.edu/library/exhibits/BreakingGround/dohan.html.

James, Edward T., Janet Wilson James, and Paul S. Boyer. Notable American Women, 1607-1950: A Biographical Dictionary, Volume 2. Belknap Press, 1971.

Morrow, Katherine Dohan. “Edith Hayward Hall Dohan, 1879-1943.” Breaking Ground: Pioneering Women Archaeologists, edited by Getzel M. Cohen and Martha Sharp Joukowsky, 274-297. University of Michigan Press, 2004.

Mount Holyoke Alumnae Quarterly, Vol. 1, January 1918, No. 4.

The Mount Holyoke XIX, no. 6, 1910.

Valente, A.J. Rag Paper Manufacture in the United States, 1801-1900: A History, with Directories of Mills and Owners. McFarland & Company, 2010.

Yale University, Class of 1872. Yale’s Biographical Record of the Class of 1872, Volume 2. New Haven: Tuttle, Morehouse & Taylor, Printers, 1892.

Yale University, Class of 1872. Yale’s Biographical Record of the Class of 1872, Volume 4. New Haven: The Tuttle, Morehouse & Taylor Co., 1913.

Written by Mapricionne “May” McQueen, Class of 2017

- Paula Debnar, “Marion Blake’s Early Years: Student, Teacher, Scholar,” Musica & Sectilia (2010): 34. ↵

- Edward T. James, Janet Wilson James, and Paul S. Boyer, Notable American Women, 1607-1950: A Biographical Dictionary, Volume 2. ↵

- Katherine Dohan Morrow, Breaking Ground: Pioneering Women Archaeologists, 275. ↵

- Yale’s Biographical Record of the Class of 1872, Volume 4. ↵

- Edward T. James, Janet Wilson James, and Paul S. Boyer, Notable American Women, 1607-1950: A Biographical Dictionary, Volume 2. ↵

- Yale’s Biographical Record of the Class of 1872, Volume 2. ↵

- Katherine Dohan Morrow, Breaking Ground: Pioneering Women Archaeologists, 275. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid., 276. ↵

- Ibid., 275. ↵

- Yale’s Biographical Record of the Class of 1872, Volume 4. ↵

- Katherine Dohan Morrow, Breaking Ground: Pioneering Women Archaeologists, 276. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Edward T. James, Janet Wilson James, and Paul S. Boyer, Notable American Women, 1607-1950: A Biographical Dictionary, Volume 2. ↵

- Cheryl Claassen, Women in Archaeology, 45. ↵

- Bryn Mawr College, Edith Hall Dohan, http://www.brynmawr.edu/library/exhibits/BreakingGround/dohan.html. ↵

- Katherine Dohan Morrow, Breaking Ground: Pioneering Women Archaeologists, 278. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Bryn Mawr College, Edith Hall Dohan, http://www.brynmawr.edu/libr

ary/exhibits/BreakingGround/dohan.html. ↵ - Ibid. ↵

- Katherine Dohan Morrow, Breaking Ground: Pioneering Women Archaeologists, 279. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid., 278. ↵

- Ibid., 279. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Edward T. James, Janet Wilson James, and Paul S. Boyer, Notable American Women, 1607-1950: A Biographical Dictionary, Volume 2. ↵

- Bryn Mawr College, Edith Hall Dohan, http://www.brynmawr.edu/library/exhibits/BreakingGround/dohan.html. ↵

- Katherine Dohan Morrow, Breaking Ground: Pioneering Women Archaeologists, 282. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid., 283. ↵

- Cheryl Claassen, Women in Archaeology, 42. ↵

- Katherine Dohan Morrow, Breaking Ground: Pioneering Women Archaeologists, 284. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid., 285. ↵

- Ibid., 287. ↵

- Ibid., 282. ↵

- Ibid., 286. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid., 288. ↵

- Bryn Mawr College, Edith Hall Dohan, http://www.brynmawr.edu/library/exhibits/BreakingGround/dohan.html. ↵

- The Mount Holyoke XIX, no. 6 (February 1910): 434. ↵

- Katherine Dohan Morrow, Breaking Ground: Pioneering Women Archaeologists, 295. ↵

- Cheryl Claassen, Women in Archaeology, 47. ↵

- Edward T. James, Janet Wilson James, and Paul S. Boyer, Notable American Women, 1607-1950: A Biographical Dictionary, Volume 2, 497. ↵

- Katherine Dohan Morrow, Breaking Ground: Pioneering Women Archaeologists, 288. ↵

- AJ Valente, Rag Paper Manufacture in the United States, 1801-1900: A History, with Directories of Mills and Owners. ↵

- Marshall Joseph Becker, Philip P. Betancourt, Richard Berry Seager: Archaeologist and Proper Gentleman. ↵

- Edward T. James, Janet Wilson James, and Paul S. Boyer, Notable American Women, 1607-1950: A Biographical Dictionary, Volume 2. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Mount Holyoke Alumnae Quarterly, Vol. 1, January 1918, No. 4, 201. ↵