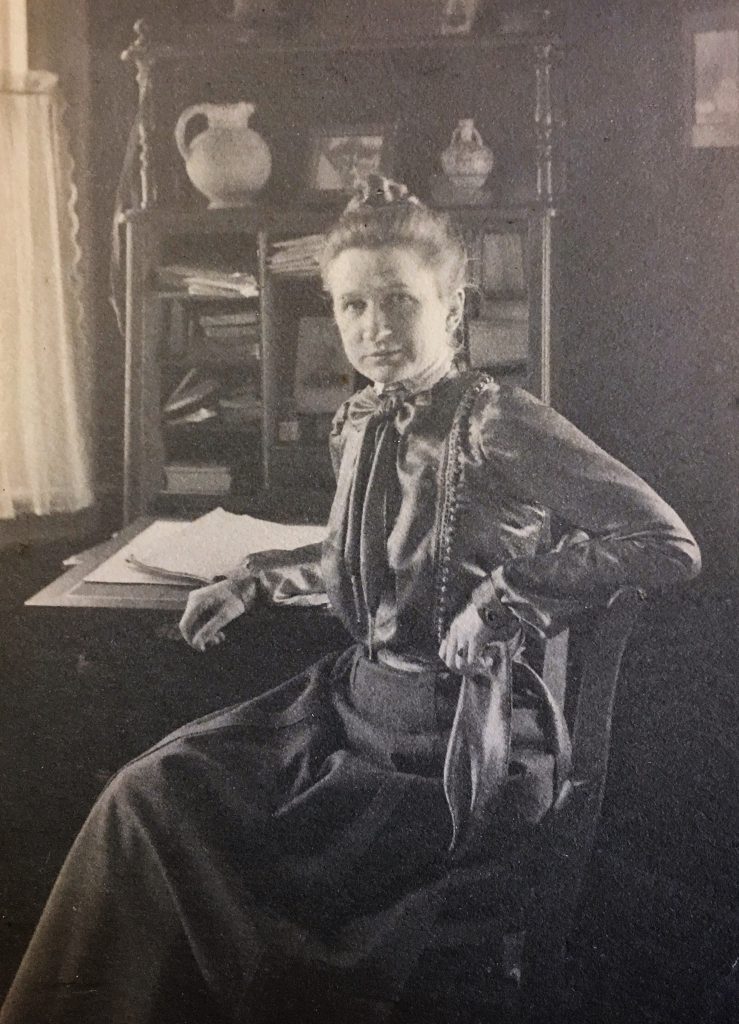

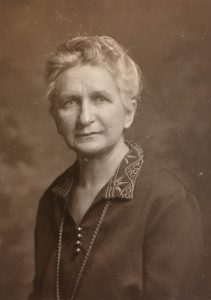

Nurse, teacher, wife, mother, activist. These words describe pioneering archaeologist Harriet Ann Boyd, later Hawes. Yet, they do not suffice in studying her work or her character. Boyd is best known for her discovery and excavation of the ancient Cretan city of Gournia, but her lesser known humanitarian efforts are equally laudable. For Boyd, promise was born from passion, never from what was expected. At the inauguration of her alma mater, Smith College’s second president in 1910, Boyd was awarded and honorary Doctor of Humane Letters, and her introduction aptly read:

…to distinguished achievements in the service of the humanities in laying bare and interpreting the buried secrets of two ancient civilizations, she has added also the fine devotion of the service of humanity in organizing and administering aid in camp and hospital to the sick and wounded in two recent wars. 1

Instead of remaining in the classrooms of America where her Smith professors wished she would, she ventured out to become the first woman to ever lead an excavation in Crete, a celebrated war nurse, and an honored academic. The scope of her life and career is truly inspiring, and the work of this project only sheds light on certain aspects. I encourage all who are interested in this extraordinary woman to explore her vast collection of materials at the Smith College Archives.

Early Life and Education

Harriet Ann Boyd was born on October 11, 1871 in Boston, Massachusetts. She was the fifth child, and only daughter of Alexander and Harriet Boyd. When young Harriet was just ten months old, her mother died, and her father never remarried. Her lack of a mother figure, Boyd’s daughter, and biographer Mary Allsebrook writes was why Boyd never became “a proper Victorian Lady” 2 In their mother’s absence, her four brothers shaped her character, making her “tough”, a quality that would stay with her for her whole life 3 Of her brothers, she was closest with the second oldest, Alex, who is credited with instilling a love for the ancient world. She completed her schooling at Prospect Hill School in Deerfield, Massachusetts 4 There she focused on classical studies, a path that would eventually lead her to be the first woman to lead an excavation in Greece. Alex fell ill in her last year at Prospect Hill, and while he made a quick recovery, he passed away in August of 1891, the summer before Boyd completed her Bachelor of Arts degree.

In 1888, she began her studies at Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts as a member of the fourteenth first-year class. It seems a known fact to her friends and family that though she was very capable, she never cared much for studying 5 A letter from the Smith faculty to Boyd after her sophomore year reads: “You can hardly be surprised to hear that the Faculty does not feel satisfied with the character of your college work last year” 6 During her time at Smith, Boyd received “a flicker of the future” when she attended a lecture given by Egyptologist Amelia Edwards 7 Another glimpse into her future came with a realization during her junior year of her understanding of “human suffering”; she would eventually become a relief worker and nurse in Greece, and would later create and direct the Smith College Relief Unit in France during the first World War 8 Boyd began teaching Classics in Harrison, North Carolina in 1892 after earning her B.A., and taught for three more years in Wilmington, Delaware. Though she had considered it before, the death of her father in April of 1896 served as the impetus to further her knowledge of the Classical World 9 In October of that year Boyd began a European tour, still undecided whether to explore Greece in the flesh, or to study literature in England. During the journey, Boyd met the brother of archaeologist Louis Dyer, who said to her “Why go to England and study Homer and Plate under dull, grey skies, when Greece is there to teach you more than you could ever learn in books?” 10 Her lifelong love for Greece began the moment she entered the country, and she began at the American School of Classical Studies at Athens days later.

Field Trips and Battlefields

Her first year at the School at Athens was met with difficulty. As one of the School’s two female students, Boyd experienced exclusion from School field trips, as well as exclusion from the School’s annual report, all at the hands of director Rufus B. Richardson. The visiting professor from 1896 to 1897 was J.R. Sitlington Sterrett “of Amherst College”, a mere eight miles from her own alma mater 11 Sterrett was decisively less exclusive, and noted the

women’s “pluck and courage” during certain trips 12 Boyd’s

sojourn in Greece initially revolved around her studies, but politically tumultuous times led her to begin first-aid classes in 1897 13 That April as her first year in Greece came to a close, Boyd served as a nurse in the Greco-Turkish War and earned the Red Cross Medal from Queen Olga ofGreece 14 During her service, she met an influential Greek nurse Sophie Baltazzi, with whom she would remain friends for life 15

Boyd returned to the United States in September of 1897 planning to spend a year preparing for an archaeology fellowship, either that of The Archeological Institute of America, or the American School at Athens 16 On July 7th, Boyd learned via a telegraph sent by Benjamin Ide Wheeler that she earned the Archeological Institute’s fellowship 17 That same month, she was called to work as a nurse in Florida during the Spanish-American War 18 The war ended before the academic year began, allowing Boyd to tackle, quite characteristically, every presented opportunity. Boyd’s second year in Greece proved more politically “peaceful”, giving her time “to find her own way in archaeology” 19 A contemporary from her time at Smith, Blanche E. Wheeler joined her in this year’s trips, and contributed greatly not only as a scholar, but as a friend. Notably, as an archaeologist Boyd never acquired antiquities. The only known collection she possessed, started in 1898, was one of “eighty-one coins, but only one, given to her daughter, can be found today” 20 She is quoted as saying “I never was a collector but a detective and cared for what fed my mind and heart” 21 As an archaeological “detective”, Boyd persevered through another year of Richardson’s exclusivity, and found a true calling in excavating instead of theoretical research.

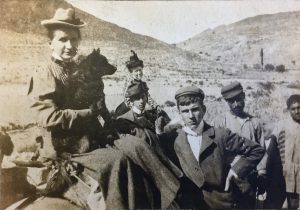

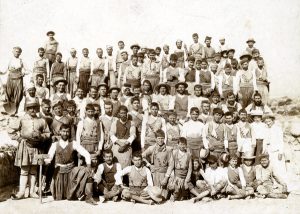

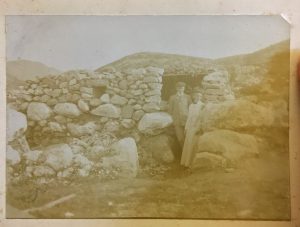

While the Agnes Hoppin Memorial fellow in 1900, a position funded by Bryn Mawr, Boyd remained in Greece for a third year. She focused her efforts and personal funds to the Island of Crete, where she accomplished the great feat of excavating Kavousi. According to some of Boyd’s memoirs published by the Archeological Institute of America, sites were becoming available for excavation around the time she started the fellowship. Once Crete gained autonomy from the Ottoman Empire in the late 1890s, countries such as England, Italy, and France “applied for sites on which to excavate” 22 Once Spring arrived, Boyd contacted the necessary authorities in hopes of gaining permission to excavate in Crete. Of these were Nikolaos Stravakis the director of customs in Crete, and prominent archaeologist David George Hogarth 23 With Stravakis’ help, Boyd along with her “three trusted friends” American botanist Jean Patten, Greek foreman Aristides Pappadhias, and his mother Angeliki, known as “Manna”, Boyd set forth for Crete 24 The excavations at Kavousi that followed from May to June satisfied the relatively inexperienced Boyd, and fueled her desire to excavate.

After the Agnes Hoppin fellowship, Boyd returned to Smith in 1900 and taught Modern Greek, Greek Archaeology, and Epigraphy at the college, a position she held intermittently between 1900 and 1906 25 Her written work “Excavations at Kavousi, Crete 1900” became her thesis, and in 1901 she earned her Master’s degree from Smith College. The American Journal of Archaeology also published the thesis, giving her well-deserved, though not universally excepted recognition in her field. Male contemporaries did not see the finds as impressive, and in fact they were ignored in Richardson’s annual report for The American School, even though Boyd’s was the only excavation other than his own at Corinth affiliated with the School in 1899-1900 26

Though she had moderate success in Kavousi, Boyd’s greater claim to fame would come in the Spring of 1901 when she directed the excavation of the Cretan Bronze Age city of Gournia. The city became known

as the “Minoan Pompeii” because it was preserved so well 27 Because the excavation of 1901, and the successive digs in 1903 and 1904 were supported (though not completely funded) by The American Archaeological Society in Philadelphia, many of the items found at Gournia belong to the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology’s collections, while others remain in Crete at the Heraklion Archaeological Museum. Unfortunately, due to her philosophy regarding collecting, her alma mater holds none of the objects, which include pottery sherds, fully preserved pottery, and tools. The correspondences, articles, and records from this time detail not only the discoveries made at Gournia, but the minutia of daily life with her crew and their human connections with Boyd, as well as her character. One New York Times article said this of her approach to working in the field:

“She calls her explorations ‘campaigns,’ and treats them as if they were battles by determined, scientific armies to wrest the secrets of ancient days from the earth. She is a general too, for she is in command of a little army of her own… [she is] unassuming in her ways, modest, direct… Yet one of the leading scientific investigators of the time…” 28

In March of 1903, after slighting and doubting her for years, Richardson “no longer ignored Boyd’s work and invited her to speak on her excavations at Gournia” at the American School in Athens 29 On her second to last excavation in Crete, funded by the “affluent Philadelphia couple” Mr. and Mrs. Houston, Boyd brought along artist and friend from Northampton Adelene Moffat who drew pottery and Richard Berry Seager a young archaeological novice 30 The next year, in her last excavation season, Boyd worked again with Seager, as well as a Smith graduate Edith Hayward Hall.

Around this time, Boyd met British archaeologist, professor, and later museum director Charles Henry Hawes, whom she would eventually marry. They were engaged in the summer of 1905. A December 1905 newspaper headline announcing their engagement read: “Delved in Ruins, Now They’ll Wed: Miss Harriet A. Boyd, Discover of Ancient Gournia, Engaged to Prof. Hawes, the English Archaeologist” 31 In Boyd’s final Cretan season in 1905, she worked on developing her research for publications, but did no more excavating. Seager also worked with Boyd again in this season, and eventually inherited her excavation permits with Hall after she left the field for academia, family life, and activism.

Marriage, Honors, and Further Volunteer Work

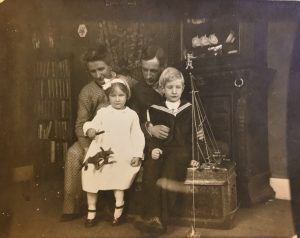

In March of 1906, Boyd married Hawes in Washington D.C. The couple had two children: Alexander Boyd Hawes, born in December, 1906, and Mary Nesbit Hawes, born on August 25, 1910. The years from 1906 to the end of her life in 1945 seem to be characterized by three fundamental forces in Boyd’s life: her connection to Smith College, her desire to serve others, particularly in Greece, and her humble, loyal, yet tenacious nature. Less than two months after her daughter’s birth, Boyd received an Honorary Doctor of Humanities degree at the inauguration of the college’s second president Marion LeRoy Burton. The early years of their marriage required much travel and relocation, as the family lived in Madison, Wisconsin, Oxford, England, Hanover, New Hampshire, and eventually Boston, where Harriet and Henry would spend the rest of their professional careers.

Having family duties did not deter her from work; her 1908 book detailing her most successful work at Gournia which remains a relevant and high quality piece of scholarship, and generously credits Seager, Hall, and Wheeler as co-authors was published shortly after moving to Madison, while caring for a young child 32 The couple was involved in relief efforts during the first World War. Hawes returned to his home country, and Boyd found herself a nurse once again, first in 1914 on the island of Vidos running a transit camp for Serbian soldiers, and then in August of 1917 when she “became director of the Smith College Relief Unit” 33

Following the war, Boyd lectured in pre-Christian art at Wellesley College from 1920 until 1936, while Hawes was assistant director-bursar of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston from 1919 until 1924, and then associate director until his retirement in 1934 [ 34. Ibid, 239.] The position at Wellesley, as well as her occasional lectureship at the Museum, broadened her research and led to her planned but never published works: Five Riddles of Greek Art, and The Hellenic World and Christianity: An Historical Study 34 The “five riddles”, in her words included the Ludovisi throne, the Parthenon pediments, and the Erechteum 35 These written works, published or not, stemmed from her endeavors during her time at the American School almost twenty years previous, showing her enduring love for Classical Archaeology, particularly prehellenic Archaeology.

The following years, Boyd’s selfless spirit led her to a period of activism. While she was busy at Wellesley, she took on political and social issues of the time, particularly after 1926 36 She wrote letters to President and First Lady Roosevelt, as well as other leaders on various issues regarding foreign and domestic policy 37 Among Boyd’s causes, one of the most famous was her support for The East Cambridge strike in Cambridge, Massachusetts for which she was sued for one-hundred-thousand-dollars, “which was eventually withdrawn.” 38 Soon after her retirement in June, 1936, the Haweses moved close to Washington D.C. to a farm called Belle Haven in Alexandria, Virginia 39 Here the couple could live nearer to their married children and grandchildren, and so Boyd, 65-years-old at this point, could become involved on the ground in Washington. A trip to Prague and Germany at the start of the second World War with her journalist daughter sparked Boyd’s anti-war efforts, mostly by way of letter writing. By December, 1943, Henry passed away at Belle Haven. Boyd, with “her own health deteriorating”, still planned to one day return to “her ‘adopted’ country” in early 1945 40 In February of that year she wrote:

I believe I couldn’t do better with the rest of my life short or long than to help Greece all I can. 41

Boyd passed away just a month later on March 31, 1945.

Timeline

1871

October 11, Born in Boston.

1888

June, Graduated from Prospect Hill School.

September, Starts school at Smith College.

1891

August 26, Death of brother Alex Boyd.

1892

June, Graduates from Smith College.

Teaches in South Carolina until 1893.

1893

Teaches in Delaware until 1896.

1896

April 4, Death of father Alexander Boyd.

October, Starts at the American School of Classical Studies in Athens.

1897

Political unrest in Greece.

Begins her now lost coin collection.

April, Fails nursing exam; still becomes Red Cross nurse after appealing to Queen of Greece.

April-May, Meets, befriends Sophie Baltazzi, upper class Greek nurse.

Academic year, Returns to United States, studies for fellowship exams until 1898.

1898

July, Serves as nurse in Florida during Spanish-American War.

September, Archaeological Institute of America fellow at the American School in Athens.

December, Crete gains autonomy.

1899

September, Bryn Mawr’s Agnes Hoppin Memorial fellow at the American School in Athens; eight of the fifteen students are women.

1900

Spring, Leaves for Crete for the first time.

April, Writes letter requesting excavation sites to Nikolaos Stavrakis, director of customs in Crete; Iosef Hazzidakis, ephor of antiquities in Eastern Crete, approves project.

April 17, Sets off for Gortyna, gets excavation advice from archeologists David Hogarth, Arthur Evans, Federico Halbherr.

May, Uncovers findings at Kastro near Mouri t’Azoria; Skouriasmenos and Vronda.

September, Starts lecturing at Smith College in Greek archaeology, epigraphy, and Modern Greek.

December, Gives first presentation on Kavousi at the Archeological Institute of America in Philadelphia; meets Sara Yorke Stevenson.

1901

April, Arrives in Crete again, but self-funded this time; renews Kavousi permit.

June, Receives permit for preliminary excavation of Gournia; finds a palace, a shrine, many houses.

September, Returns to lecturer position at Smith College.

December, Presents Gournia research at Archaeological Institute of America meeting; garners great praise.

1903

January, Studies in antiquities in Egypt, then in Athens.

1903

March, Invited by Rufus Richardson, Director of the American School in Athens, to speak about her work; meets Mr. and Mrs. Houston.

1903

March, Full scale excavation of Gournia.

November – February 1904, Returns to United States; Works with Greek immigrants at Jane Addams’ Hull House.

1904

March, Arrives in Athens; final excavation campaign in Crete.

May, Meets (Charles) Henry Hawes in Crete.

1905

March, After returning to the United States again, returns to Crete to develop her research of Gournia.

Fall-Winter, Returns to the United States; signs over her remaining excavation permits to Richard Seager, a young archaeologist she worked with at Gournia.

1906

March 3, Marries Henry Hawes in Washington D.C.

December 3, Son Alexander Boyd Hawes is born.

1907

September, Family moves to Madison, Wisconsin where Henry is a professor at the University of Wisconsin.

1908

November, Book, Gournia, Vasiliki and other prehistoric sites on the isthmus of Hierapetra, Crete; excavations of the Wells-Houston-Cramp expeditions, 1901, 1903, 1904.

1909

Spring-Summer, Family moves to England, settles in Oxford.

December, Henry and Harriet co-author and publish Crete, the forerunner of Greece.

1910

February, Family moves to Hanover, New Hampshire, where Henry is a professor of anthropology at Dartmouth College.

August 25, Daughter Mary Nesbit Hawes is born.

October 5, Awarded an honorary Doctor of Humanities degree by Smith College.

1912

Raised funds for Greek soldiers and refugees during the Balkan War.

1916

February – April, Ran a transit camp at island of Vidos for Serbian soldiers; returns to United States after.

1917

April 6, United States declares war against Germany.

August, Begins directing the Smith College Relief Unit in Grécourt, France; Henry does administrative work in England at the same time.

1919

Summer, Returns to the United States; Henry is appointed the assistant director of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, and the family moves to Boston.

1920

Fall, Begins teaching at Wellesley College.

1921; 1923

Presents papers of new research at the Archeological Institute of America in Philadelphia.

1926

Spring, Takes short trip to American School in Athens for a ceremonial library opening; brings children and conducts personal research.

1932–1933

Engages in political involvement; involvement in a shoe factory strike.

1936

Retires from teaching at Wellesley College; moves with Henry to D.C.; engages in political activism.

1938

September, Joins daughter Mary, a reporter, in Prague; sees Hitler on campaign.

1939

September, World War II begins.

1943

December 13, Henry dies at age 76.

1945

March 31, Harriet dies at age 74.

Works Cited

Allsebrook, Mary. Born to Rebel: The Life of Harriet Boyd Hawes, Edited by Annie Allsebrook. Oxford: Oxbow Books, 1992.

Brown, Ann, and Vasso Fotou. “Harriet Boyd Hawes (1871-1945),” in Breaking Ground: Pioneering Women Archaeologists, Edited by Getzel M. Cohen, Martha Sharp Joukowsky, 198-273. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 2006.

Hawes, Harriet Boyd. “Memoirs of a Pioneer Excavator in Crete.” Archaeology 18, no. 2 (1965) : 94-101.

Hawes, Harriet Boyd. “Part II: Memoirs of a Pioneer Excavator in Crete.” Archaeology 18, no. 4 (1965) : 268-276.

Harriet Boyd Hawes Papers, Smith College Archives.

Written by Emma Raleigh, Smith College 2017

- Harriet Boyd Hawes Papers, Smith College Archives. ↵

- Mary Allsebrook, Born to Rebel: The Life of Harriet Boyd Hawes, ed. Annie Allsebrook (Oxford: Oxbow Books, 1992), 1. ↵

- Ibid, 1. ↵

- Ibid, 9. ↵

- Ibid, 10. ↵

- Ibid, 10. ↵

- Ibid, 11. ↵

- Ibid, 11. ↵

- Vasso Fotou and Ann Brown,“Harriet Boyd Hawes (1871-1945),” in Breaking Ground: Pioneering Women Archaeologists, ed. Getzel M. Cohen and Martha Sharp Joukowsky, (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2006), 200. ↵

- Ibid, 200. ↵

- Ibid, 201. ↵

- Ibid, 201. ↵

- Ibid, 202. ↵

- Ibid, 203. ↵

- Ibid, 202. ↵

- Ibid, 203-204. ↵

- Harriet Boyd Hawes Papers, Box 1, Folder 10, Smith College Archives. ↵

- Fotou and Brown, 204. ↵

- Ibid, 202; 205. ↵

- Ibid, 206. ↵

- Ibid, 206. ↵

- Harriet Boyd Hawes, “Memoirs of a Pioneer Excavator in Crete,” Archaeology 18, no. 2 (1965): 95. ↵

- Fotou and Brown, 209-210. ↵

- Ibid, 210. ↵

- Ibid, 204. ↵

- Ibid, 216. ↵

- Ibid, 227. ↵

- Allsebrook, 114. ↵

- Fotou and Brown, 226. ↵

- Ibid, 226. ↵

- Harriet Boyd Hawes Papers, Box 4, Smith College Archives. ↵

- Fotou and Brown, 237-238. ↵

- Ibid, 238. ↵

- Ibid, 242. ↵

- Ibid, 240. ↵

- Ibid, 242. ↵

- Ibid, 242. ↵

- Ibid, 242. ↵

- Ibid, 242-243. ↵

- Ibid, 244-245. ↵

- Ibid, 245. ↵