For Miss Randolph there seemed to be no other college than Mount Holyoke and no other Department of Art than ours.1

If you wander along the staircases and corridors of the Art Building at Mount Holyoke College you may notice the plaster casts of sculptures and reliefs that line its walls. These casts, most of which were acquired between the late 19th and first half of the 20th century, are testaments to the changes in culture, taste, and education that have occurred in the many generations since the inception of the United States as a Republic.2

[slideshow_deploy id=’1404′]

The casts were acquired when few original European works of art were available and the American art scene was still developing its own identity. A cast mania grew as they proved to be a useful aid to emerging collegiate institutions and museums, offering access to a classical world which represented the values of the new nation.

Over time, these plaster casts gained and lost their value. After having been revered in collegiate collections and museums across the country, the growing demand for original works in the 20th century led to the destruction and disposal of the majority of the casts. Today, they are once again in the spotlight as they are representative of art collecting and themselves original creations that slightly vary between cast makers, who dedicated their skills to making the most perfect replicas.

Mount Holyoke is fortunate to still own a considerable number of the finest quality, most of which were made directly from originals and are true to size. These casts were once central to class instruction and helped shape the curriculum and the collection. It was Louise Fitz Randolph’s dedication to the advancement of the collection that brought these casts to the college. Randolph’s efforts mark the inauguration of years of unabating progress in the collection, creation, and education of art and history.

A Space for the Arts

It was in 1892, after two and a half years abroad, that Randolph joined the Department of Art at Mount Holyoke College. She continued to serve Lake Erie Seminary jointly and was thus head of both departments until 1896. As a Mount Holyoke alumna, Randolph knew well the value of time and discipline and promptly after her arrival took on the mission of expanding the Department of Art so as to fit the needs of the students.

On January 1, 1897, after only four years as chair of the department, Randolph drafted a personal appeal to the college.3 The letter commented on the necessity for an art building at Mount Holyoke that would “meet the growing demands of the department.”4

[slideshow_deploy id=’1461′]

In her letter she specified what would be the most suitable structure, mentioning Wellesley’s Farnsworth Hall as a model that combined an exhibition space with lecture rooms and art studios. She stated that for the sake of teaching, the exhibition space should include a

cast gallery along with photographs that were to be “scientifically arranged in some historical sequence” in order to grant the students a cohesive narrative of art and history. The lecture room would allow the illustrations used in classes to be available at all times to those who wished to use them and the connecting studios would give space for the drawing and painting courses that were sometimes offered as a lab to students taking art history courses. Randolph made public with this letter more than the necessity for an art facility, the arrangement that would be most fitting for the purpose of teaching. Taking into consideration how the structure would help the students receive a well-rounded education in art and archaeology, she specified the manner in which the building was to create for the students a lifelike, palpable classroom experience that mirrored closely the real places and objects discussed. These didactic yet dynamic approaches to teaching transformed the learning experience and were the true underpinnings of the Mount Holyoke collection. It was during this time that art itself became a valuable resource to the American liberal arts curriculum, seen in the development of public museums in the United States.5

Mount Holyoke added itself to the few institutions that set precedent for the way in which the fields of art history, archaeology and Classics were taught6 and most notably, how they used museum collections as an invaluable component in their methods.

The New Museum: Dwight Art Memorial Hall

If it had not been for Miss Randolph I suppose there would have been an art building at Mount Holyoke, but it would not have come so soon.7

The appeal for an art building was received with support by the administration and it was decided that Dwight Art Memorial Hall would house the collection and provide the needed space for the expansion of the department. In the following years, as the construction of Dwight Hall began, Randolph published an itemized purchase list of casts noting those that would be of most interest to the college and suggesting locations where to purchase them while “she saw to it that the castes obtained were the most perfect that could be made.”89 The replicas were to enrich the success of Dwight Hall which, as she wrote in a letter to alumnae in the later months of 1897, “depended largely upon its proper equipment.”

She called on graduates to make contributions in their names to the development of the department namely in the purchase of casts and in the establishment of an endowment for the acquisition of art. Randolph emphasized the importance of “equipment” over “environment,” stating that the building itself was “eloquently prophetic” but was in need of a steady endowment that would “maintain the hall and add each year to the collections.”10

[slideshow_deploy id=’1477′]

Randolph’s name will always be closely associated with these efforts to solidify the Mount Holyoke collection, especially as it made its way into Dwight Hall, a moment which marks also the expansion of the Department of Art and Archaeology. More specifically, Randolph’s fascination with the plaster casts and her dedication to the careful selection of each and every one of them gave to Mount Holyoke, as she herself noted, “an invaluable possession in connection with the teaching of sculpture and archaeology.”11

In 1901, a year prior to the opening of the Dwight Art Memorial Hall, Randolph traveled for eight months, presumably in search of casts, photographs, and original objects to add to the collection. After two years of construction and five years of travel, negotiation, meticulous organization, and thought on the part of Randolph and the department, Dwight Art Memorial Hall rose in 1902. The building stood thanks to Randolph’s ability to dedicate herself with “whole heart and mind… (to) the perfecting of this monument, raised through her own mediation, to her beloved art in her beloved college.”12

Honors and Donations

Randolph’s name became synonymous with the cast collection so that years later the gallery in Dwight was renamed “ The Louise Fitz-Randolph Gallery of Casts” in gratitude for her efforts.13 In 1904 Mount Holyoke awarded Randolph an honorary Master of Arts degree in recognition of her years as professor and key developer of the college.

In the years 1909-1910 she spent another 14 months abroad, during which time she acquired objects both for the college and her personal collection. This included a large number of Egyptian objects, from shabtis to reliefs and wall fragments to glass shards which would all offer glimpses into the thought, resources, and innovations of early civilizations. To Randolph these small items that might seem mundane were fundamental to the students’ understanding and a well-rounded education. She contributed many items from her personal collection to Dwight in order to more closely fill the narrative that she set out to create. Many of these objects were donated by her personally and others were donated in her name following her death.

Mount Holyoke Forever Shall Be!14

Throughout her later years she continued with scholarly zest to follow all current studies and discoveries in her field.15

In 1912, after 20 years of devotion to Mount Holyoke, Randolph was appointed Professor Emeritus of Archeology and the History of Art following her retirement. She settled in South Hadley in the faculty house and traveled domestically and abroad.16 Randolph continued to provide counsel in the acquisition of art at Mount Holyoke and maintained close ties with the college, attending events and contributing pieces to the Alumnae Quarterly.

Randolph died December 29, 1932 during a visit to her sister and her niece, Caroline Ransom Williams, in Toledo Ohio.

[slideshow_deploy id=’1496′]

Legacy

A personality of unusual force, individuality, and charm, whose achievement must be remembered as a contribution not only to the work of Mount Holyoke College but also to the development of the liberal arts curriculum in other American colleges.17

Louise Fitz Randolph lived an eventful and fruitful life of travel, leadership, and passion. The educators and students that surrounded her witnessed in one lifetime the complete transformation of spaces for the teaching and appreciation of art history. Her contemporaries learned from her attention to detail and her courage to travel to faraway places as a 19th century woman and make negotiations on behalf of an American institution. Her presence at Mount Holyoke far transcends her 20 years at the college and her name continues to reemerge every time the history of the art and cast collection are mentioned.

Letters from the months following Randolph’s death show the admiration and love that colleagues, friends, family, and students had for her. Her niece, Caroline Louise Ransom Williams, saw to it that a lot of her aunt’s remaining art collection, as well as some documents and photographs relating to her life at the college, made their way to Mount Holyoke. It is possible that personal correspondence and writings that were considered private and of no use to the college were kept in the family, so some mysteries still remain about Randolph’s life.

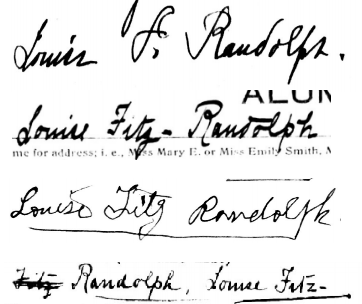

Although a woman of intimidating accomplishments, one can speculate from the little that is known of her personal life that she was proud, but humble. Randolph showed signs of a relatable life, at times wanting to sleep for months after finally getting through a semester and of what one can jokingly call conflicting identities: not being able to decide whether she wanted to abbreviate her middle name or hyphenate it to her last name. 18

As of 2016 Randolph’s name can be seen in several locations across the campus: on many donor labels in the museum, on an informational label in the staircases that now house the plaster casts, and scattered across folders and boxes in the archives and museum files. A postgraduate fellowship offered by the Mount Holyoke Department of Art History is also named in her honor. The Mount Holyoke College Art Museum celebrated 140 years and continues to expand its collection very much in the same manner that Randolph did: gathering resources and donations from alumnae, benefactors, and organizations. As Louise Fitz Randolph herself wrote: “In the work in Art and Archaeology there is no break with the traditions of the past.” 19

Miss Lyon would say of her, I think that she approached closely her ideal for Mount Holyoke’s daughters–that they should be “as corner stones, polished after the similitude of a palace.20

Timeline

1851

On June 25th she was Born in Panama, New York to Julia Bell and Reuben F. Randolph.

1866

In the summer and spring she taught country district school in Panama, New York.

1866-69, 1870-71

Taught in Sharon, Pennsylvania.

1871-1872

Attended Mount Holyoke Seminary (Graduates MHS in 1872.)

1874-76

Taught in Toledo, Ohio.

1876-96

Taught at Lake Erie Seminary (Head of Art Department from ca. 1882-1896.)

1881-1910

Intermittent Europe travel and study: 1881-84, 1885,1887, 1889-92, 1894, 1901, 1903, 1905, 1907, 1909-10 (Refer to ‘Travel and Study’ section for details.)

1884-92

Gave art and archaeology lectures at Lake Erie and the Cleveland School of Design.

Time at Mount Holyoke

1892-1912

Head of Department at MHC, Titles as follow:

1892-1901 Head of the Department of Art at Mount Holyoke College

1901-1912 Head of the Department of Archaeology and History of Art (along with Jewett)

(Served Lake Erie and MHC jointly from 1892-1896)

1897

On January 1st she wrote an open letter highlighting the need for an art building at Mount Holyoke.

1897

In June she published a purchase list of casts being requested by Mount Holyoke.

1902

Dwight Art Memorial Hall opens.

1904/05

Received honorary Master of Arts degree from Mount Holyoke.

1912

Is appointed Professor Emeritus of Archeology and History of Art.

1927

Conducts research in Egypt.

1912-32

Settled down in South Hadley post retirement.

1932

On December 29th, Died in Toledo, Ohio while visiting her relatives.

Travel

1881-84 (3 years),1885 (5 months), 1887 (6 months), 1889-92 (2 ½ years), 1894 (Summer), 1901 (8 months), 1902 (summer), 1903 (summer), 1905 (summer), 1907 (summer),1909-10 (14 months).

Studied at the following institutions abroad:

Oxford University, South Kensington Museum (Victoria and Albert Museum,) British Museum, Sorbonne, Ecole des Beaux Arts, Paris, University of Berlin, University of Zurich, American School of Classical Studies in Rome and Athens.

Works Cited

ASCMHC = South Hadley, Massachusetts, Archives and Special Collections, Mount Holyoke College:

LFR Files = Louise Fitz-Randolph Files, LD 7092.8

An Art Building for Mount Holyoke College, January 1, 1897

Census of College Women, 1915

Death Correspondence, Letters surrounding LFR’s death, 1933

Letter to Alumnae, 1897

Life, ca. 1912

Faculty Letter, 1933

Class of 1872 File

Class-Letter, Letter written by Louise Fitz-Randolph, 1873

Alumnae Quarterly

Louise Fitz Randolph, August 1933

Dwight Hall Files, RG 24.03

Williston Hall Files

FITZ-RANDOLPH 1918 = L. FITZ-RANDOLPH. Alumnae Quarterly, History of the Department, South Hadley, Massachusetts 1918.

FREDERIKSEN, MARCHAND 2010 = R. FREDERIKSEN, E. MARCHAND, Plaster casts : making, collecting, and displaying from classical antiquity to the present, Berlin; New York 2010.

HARRIS 1976 = J. C. HARRIS, Collegiate collections, 1776-1876: an exhibition sponsored by the Mount Holyoke Friends of Art in honor of the Nation’s Bicentennial and the Centennial of the Mount Holyoke College Art collection, South Hadley, Massachusetts 1976.

Written by Claudia M. Espinosa, Class of 2018

- ASCMHC, LFR Files, Death Correspondence, 1933. ↵

- FREDERIKSEN, MARCHAND 2010. ↵

- FITZ-RANDOLPH 1918. ↵

- ASCMHC, LFR Files, An Art Building for Mount Holyoke College, January 1, 1897 ↵

- ASCMHC, LFR Files, Faculty Letter, 1933 ↵

- The class of 1872 was the first at Mount Holyoke to receive instruction in art history. Harvard was the first institution to add art history to the regular course of study in 1875. Randolph noted that Mount Holyoke and Lake Erie came only second in 1878, year in which other institutions did the same. However, the accuracy of records is still unclear. See FITZ-RANDOLPH 1918 and HARRIS 1976. ↵

- ASCMHC, Alumnae Quarterly, Louise Fitz Randolph, August 1933 ↵

- ASCMHC, LFR Files, Letter to Alumnae, 1897 ↵

- ASCMHC, LFR Files, Faculty Letter, 1933 ↵

- ASCMHC, LFR Files, Letter to Alumnae, 1897 ↵

- FITZ-RANDOLPH 1918 ↵

- ASCMHC, Alumnae Quarterly, Louise Fitz Randolph, August 1933 ↵

- FITZ-RANDOLPH 1918 ↵

- Mount Holyoke College’s Alma Mater ↵

- ASCMHC, LFR Files, Death Correspondence, 1933 ↵

- ASCMHC, LFR Files, Faculty Letter, 1933 ↵

- ASCMHC, LFR Files, Death Correspondence, 1933 ↵

- ASCMHC, Class of 1872 File, Class-Letter, 1873 ↵

- FITZ-RANDOLPH 1918 ↵

- ASCMHC, Alumnae Quarterly, Louise Fitz Randolph, August 1933 ↵