Juan Ruiz’s masterpiece Libro de Buen Amor was published in the early fourteenth century in the Castile region of modern-day Spain. As an important literary text written in medieval Spanish at a time when most influential writings were in Latin, this piece reflects the beginning of a linguistic shift in Spain. This text consists of a variety of satirical poems and short stories on love with religious morals, reflecting influences from the Christian tradition of Europe as well as from Judaism and Islam. The Jewish and Islamic religious influences in Libro de Buen Amor reflect the changing demographics of Spain at the time and present evidence for the ways that Hebrew and Arabic affected Spanish linguistically. The fact that Libro de Buen Amor was written during a time in Spain when there was a growing unique Spanish identity and increasing outside influences from northern Africa instead of Europe can be used to understand the state of the Spanish language in the text.

The exact date of publication of Libro de Buen Amor is not known but it can be placed roughly in the first half of the fourteenth century. During this time, Alfonso XI ruled in Castile, succeeding the throne from his father Ferdinand IV in 1312 and ruling until 1350. Alfonso X, who ruled before Ferdinand IV, is largely credited with beginning the Castilian literary tradition. Known as Alfonso el Sabio, his court scholars compiled a history of Spain and a “general history”, translated Arabic scientific texts, arranged astronomical tables, and wrote many poems in Castilian (which eventually evolved to modern Spanish). This led to more standardized Castilian syntax and vocabulary and opened the way for future influential literature in Castilian instead of Latin by the time of Alfonso XI’s rule. Throughout the reign of Alfonso X, Ferdinand IV, and Alfonso XI, Spain engaged in religious wars with Muslims from Northern Africa. Spain saw a decisive victory over Morocco in 1340 under Alfonso XI and though Spain came out victorious, this did not stop the Arabic language from influencing the Spanish language as a substratum language. The other religious minority present in Spain was the Jewish people. Generally, the Jewish people were treated with tolerance in Spain until the plague hit in 1348 and they were used as a scapegoat. However, in Juan Ruiz’s time, Judaism and Christianity generally coexisted peacefully and Hebrew, like Arabic, influenced Spanish as a substratum language.

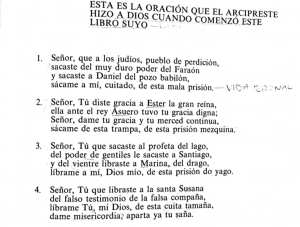

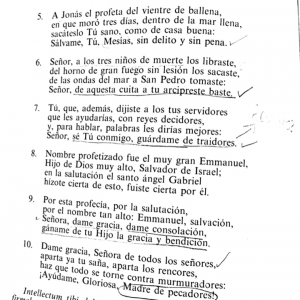

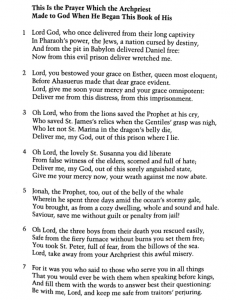

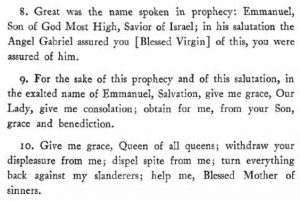

Juan Ruiz lived during the early to mid-fourteenth century and though his birthdate is not known, he died in 1351. This indicates that Libro de Buen Amor was written under the early fourteenth century influences of Alfonso X’s legacy, Alfonso XI’s rule, wars between Christians and Muslims, and before the plague. The Islamic influences on this otherwise very Christian text are clear; Américo Castro says of Ruiz: “Su arte consistió en dar sentido cristiano a hábitos y temas islámicos, y es así paralelo al de las construcciones mudéjares tan frecuentes en su tiempo” (Hamiltion, 2006). Juan Ruiz was a Christian religious figure as the archpriest of Hita, in Guadalajara. Beyond that, very little is known about Ruiz. It is possible that Ruiz was in fact more than one person, though most scholars work under the assumption that he was a single person. Additionally, some believe that he was imprisoned when writing Libro de Buen Amor, though the work does not reflect darkness and solitude that one may expect from a text written in prison; instead, it is satirical, comical, and jovial. Beyond his status as a Castilian religious cleric in the early fourteenth century, there is very little known about Juan Ruiz that can inform the background of the Libro de Buen Amor.

The intended audience of the text is controversial as well. Many believe that it was meant to be accessible to the uneducated public because of the fact that it was written in Spanish and generally transmitted orally. At the time, prestigious literature was still often written in Latin, though this was in the process of changing due to Alfonso X’s influence, so the fact that the text was written in Spanish may have indicated that it was intended to be read by the general Castilian public. Additionally, the fact that it was usually read aloud may have made it accessible to the illiterate public. However, Jeremy N. H. Lawrance argues that the sophistication of Ruiz’s language and details of his subject matter (in particular, Lawrance cites a passage discussing clerical disputes within the Church) indicate that the text was intended for an educated audience. Lawrance also argues that literature was often transmitted orally at this time, even to the educated class. This text was writing at a time of linguistic and social change in Spain so it is difficult to trace the exact intentions and audience of the text.

Libro de Buen Amor was written at a time of great socio-linguistic change in medieval Spain. Following Alfonso X’s Castilian literary tradition, Libro de Buen Amor presents a significant contribution to the beginning of Spanish literature. It reflects the various linguistic influences that Spanish felt from Arabic and Hebrew as well as the importance of Latin Christian tradition in Spain. Though little is known about Juan Ruiz or who Ruiz was writing for, it is clear that Ruiz was writing under the influence of Alfonso X’s legacy and Islamic incursions into Spain.