El Libro de Buen Amor: A Historical Account

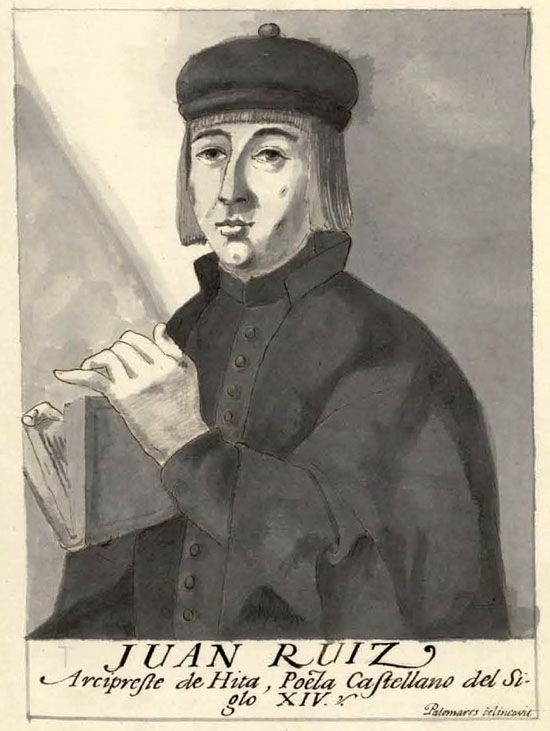

El Libro de Buen Amor is a work of Spanish poetry written by the cleric Juan Ruiz, a 14th century Spanish poet renowned for his witty and realistic explorations of love. While much of Ruiz’s life remains a mystery, scholars have gleaned information from this heavily autobiographical work. Ruiz, born in 1283 in the south-central Spanish town of Alcala, was educated in Toledo, an Islamic city and the capital of the Toledo province in Castile-la Mancha (“Juan Ruiz”). An intellectually engaged student, Ruiz was greatly influenced by a variety of works of literature such as: The Bible, ecclesiastical treatises, Ovid and other classical authors, medieval Goliard poets, and various Arabic writings. After his studies, Ruiz became the archpriest of a small village near Alcala by the name of Hita, where he wrote the first edition of El Libro de Buen Amor in 1330. In 1343 the expanded and final version of this poem was released, earning Ruiz fame and historical recognition until his death in 1350 (“Juan Ruiz”).

Perhaps one of the most celebrated and revered works of medieval Spanish poetry, Juan Ruiz’s El Libro de Buen Amor provides a lyrical depiction of life in Spain during the 14th century as well as the author’s satirical and occasionally bawdy musings on love, God, and religion. The book serves as a semi-autobiographical account of Juan Ruiz’s adventures as he attempts to grapple with two disparate forms of love– buen amor, or the true spiritual love between man and God, and loco amor, carnal love. The book contains twelve narrative poems, composed in the form of cuaderna dia, describing Ruiz’s encounters with love; namely the spiritual love between the protagonist of the poem and God, and the sexual desire he seeks to gratify by seducing several women. The work includes a parodical sermon, anticlerical satires, and a myriad of love songs, and is greatly praised for its realistic treatment of love quests, and thus demonstrates Ruiz’s ability to weave together his religious, erotic, and satirical points. Medieval life is also portrayed in a realistic and satirical manner throughout the poem, representing the people and problems ubiquitous in medieval Spain. Ruiz’s work also examines the moral ugliness of sin and death in an attempt to emphasize the importance of the spiritual love connection between man and God. Original manuscripts of this work are incredibly rare: only three medieval manuscripts survived the ages, and of these none are transcribed by the poet himself, and all have suffered minor to severe damages.

There are many different interpretations of the work, but the poetry’s true meaning is as elusive as the poet himself, vexing scholars and lovers of poetry for centuries. The debate lies in the differing definitions of “true love.” Ruiz’s work contains a multitude of hidden meanings and innuendos, but disagreements over the true intent are multifold. Scholars and casual readers alike argue over lexicon, syntax, and deeper meanings (Willis xi). The enigmatic and obscure quality of the writing reflects the intentions of the author to design a book which provokes thought and intellectual discourse among readers.

Another point of innovation in Ruiz’s work is his use of vernacular Spanish; evidenced by the presence of folk sayings and proverbs, making his book of poetry an insightful case study into vernacular middle-Spanish. Vernacular Spanish was not present in classical Spanish works of poetry, however in the medieval period its became far more prevalent. The earliest forms of vernacular poetry in Spain stemmed from heroic epics– poems that nostalgically described the great feats and deeds of past heroes, and were intended to inspire audiences to attempt heroic acts of their own. At the same time as these poems were being produced an autonomous Castilian identity was also forming, making the poems informative accounts of Castilian society. Heroic epics such as these arose during times of great political and social instability, but as the tense period passed– by the end of the 11th century– Spanish poetry was shifting its focus from national afflictions to more ubiquitous intellectual questions (Willis 75). The subsequent wave of poetry served to elucidate many characteristics of Castilian society including their most valued virtues: strength, knowledge, and a fine balance of prudence, forbearing and moderation (Willis 76). This new form of poetry also expanded its subject matter, now including a more worldly Spain– one connected to other global powers such as Greece and Germany.

By the early 13th century a new school of poetry was emerging in northern Spain called mester de clerecıa. This new style included the poetic verse cuaderna vıa, or “quatrains of monorhymed Alexandrines (or fourteen-syllable lines), divided by a central caesura” (Cambridge 78). While this is the same verse style in which Ruiz so expertly penned his masterpiece El Libro de Buen Amor, Ruiz’s work is exceptional in that it does not blindly adhere to the cuaderna via format, but furthermore contains prose at the beginning, and a variety of metrical schemes throughout the poem. While the work is still greatly admired today, and has influenced brilliant authors such as Chaucer, the context of the 14th century–markedly the diverse proliferation of various types of poetry– meant that Ruiz’s distinct writing did not exert significant influence over contemporary poetic styles (Cambridge 85).

El Libro de Buen Amor reflects the time period and society in which it was written. The book was written during the height of Spain’s Christian Period– an epoch lasting from 1260 to 1479, that was characterized by greater communication with northern Europe, an emphasis on urban developments and commerce, and the spread of Christian ideals. The church adopted a substantial role in this era, and there was a mutually beneficial relationship between the Church and State: the Church legitimized the reigning king, and the monarchy legitimized the jurisdiction of the Church. Religion was a prominent theme in general throughout this period, and the church infiltrated many prominent positions within the government including the chancellor, who would have been an ecclesiastic, the mayordomo, or a magnate who oversaw the royal domain, and the alférez, another magnate who controlled the royal army (Ginés). Bishops, magnates, monasteries, and other highly regarded religious figures were even granted immunity relieving them of certain taxes and prohibitions set by the government. King Peter II of Aragon, ruler of the kingdom from 1196 to 1213, voyaged to Rome to receive his crown from the high pope, and declared his realm a papal fiefdom, demonstrating the extent to which the church influenced the government (Ginés).

The birth of the Christian Period was characterized by a power struggle between the Castilian monarchy and the nobles, stemming from Alfonso X’s ascent to the throne in 1252. Alfonso X, also known as Alfonso the Wise, greatly emphasized the importance of literary and scientific achievement. This new focus resulted in the capital city of Toledo in reaching unprecedented heights of academic achievement as it ballooned in rank as a prestigious translation center. Toledo’s impressive translating prowess and influence would later prove to be an asset to Alfonso X as he decided to reject Latin as the translation language and instead shift to the more local, and commonly spoken, Castilian– a vernacular and early form of modern Spanish (“Toledo School of Translators”). This separation from Latin was a driving force in the development of the Spanish language, one whose importance should not be understated.

El libro de Buen Amor includes myriad depictions of the medieval Spanish peasantry, a prominent group Ruiz would have encountered often in the bucolic village of Hita. The economy of medieval Spain depended heavily on the agricultural industry, and hence on the exploitation of serfs. A variety of peasant types made up this extensive group– serfs with varying degrees of agency. The members with the fewest rights, known as the solariegos in Castile, were essentially indentured servants, tied to the land they worked and subject to their master’s every whim and abuse. The peasants with slightly more liberties in selecting their place of work, namely which feudal Lord they would serve, were the behetrías, however even their rights were greatly curbed towards the end of the 13th century. While peasants were not granted the same rights as aristocrats or religious clergy, they still exhibited a sense of independence and were surprisingly optimistic considering their situation.

Juan Ruiz’s poem, El Libro de Buen Amor, makes for a wonderful case study because the historical context is integrated with a variety of poetic styles. The work itself is a clever and ribald exploration that begs for a more nuanced view of love. He demonstrates the role of the clergy, peasants, and provides insight into the general makeup of society of his time, while simultaneously examining the historical context his work to heighten the complexity of the content. From a broader perspective, the work is remarkable because of the ability of the author to incorporate such a sophisticated and original poetic style with profound, possibly unanswerable questions, giving the poem a real air of originality and wit. The work is also fascinating to linguists due to Ruiz’s descriptions in vernacular medieval Spanish. Hence El Libro de Buen Amor is a testament to time and will be admired and debated for ages to come.

Works Cited

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Juan Ruiz.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 8 May 2018, www.britannica.com/biography/Juan-Ruiz.

Gies, David Thatcher., and Andrew M Beresford. “The Cambridge History of Spanish Literature.” The Cambridge History of Spanish Literature, Cambridge University Press, 2009, pp. 75–86.

Ginés, Juan Vernet, and Vicente Rodriguez. “Spain.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 24 Feb. 2019, www.britannica.com/place/Spain/The-rise-of-Castile-and-Aragon#ref70366.

Ruiz, Juan, and Raymond S. Willis. “Preamble.” Juan Ruiz: Libro De Buen Amor, Princeton University Press, 2015, pp. xix-liii.

“Toledo School of Translators.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 17 Dec. 2018, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toledo_School_of_Translators#Alfonso_X_and_the_establishment_of_the_School.

Pictures

https://www.google.com/url?sa=i&source=images&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwiiyOv_1PXhAhUwmuAKHfIpDDEQjhx6BAgBEAM&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.biografiasyvidas.com%2Fbiografia%2Fa%2Farcipreste_hita.htm&psig=AOvVaw3MDwxYjkWcnTHIs6U0k6XA&ust=1556639720355539

https://www.google.com/url?sa=i&source=images&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwiY_5-U1fXhAhWOUt8KHSQ3CY8QjRx6BAgBEAU&url=https%3A%2F%2Fes.wikipedia.org%2Fwiki%2FLibro_de_buen_amor&psig=AOvVaw0bZQmq5lKIVLJSzmFfithn&ust=1556639765728587