A Brief Socio-historical Introduction to El Cantar de Mio Cid

“El Cantar de Mio Cid” is the oldest preserved Castilian epic poem known to exist. Its protagonist, El Cid, born Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar, is a war hero who aided the Christians of what is now Spain to retake land occupied by Moorish invaders during the Medieval Era. The epic poem is believed to have been written between 1140 and 1207 AD, and its author is unknown.

At the time that “El Cantar de Mio Cid” was written, the Iberian Peninsula and what is now Spain had been occupied by the Visigoths, a Germanic tribe previously known for invading the Roman Empire, for years. In 711, a group indigenous to North Africa known as the Moors invaded the Iberian Peninsula, overtaking the Visigoths and controlling the entire peninsula with the exception of what lay north of the Pyrenees. The epic poem follows the heroic quest of El Cid to besiege Valencia in order to gain the land for Christian control during the Reconquista, in which Christians collectively fought to take back the Iberian Peninsula from Moorish occupiers.

During the time that “El Cantar de Mio Cid” was written, the Christians of Spain were in the middle of the Reconquista, a campaign to reconquer the peninsula from the Moorish residents. While the Moors occupied what is now Spain and Portugal, it was known as Al-Andalus, and was controlled from a main authority in Cordoba, in the south of the peninsula. A Frankish army led by Charlemagne, or Carlomagno, had occupied what is now Catalonia since around 800 AD. Technically speaking, the Reconquista had been occurring for hundreds of years, starting with the Christian victory over the Moors in the Battle of Covadonga, creating the kingdom of Asturias and thus beginning a southward military expansion of the Christians until 1492.

Around 1000 AD, the Christian kingdoms were not united under a centralized authority or statist identity. Rather, they were distinct kingdoms with their own kings, who, despite all desiring to expel the Moors of their control of the peninsula, did not view their fighting against the Moors as a united effort amongst the kingdoms, nor as a Christian crusade. The kingdoms that existed at that moment included Navarra, Aragon, Asturias, Castile, Leon, Catalonia (influenced by Frankish invaders), and the Basque Country (controlled separately by the Basques). In 1028, the King of Navarra, Sancho III, inherited Castile from a marriage, and then subsequently divides the kingdoms again when he gifts his sons with Aragon and Castile. Later, in 1085, Alfonso VI, King of Castile and Leon conquered Toledo, a central city in the peninsula. At this moment, the kingdoms were still very much individualized and lacking centrality.

Medieval Spain, while similar to other areas of Europe, has its individual characteristics. In other regions of Europe, for example, France, society was socioeconomically fragmented into three main arenas: warriors, clergy, and peasants. On the contrary, Castile at this time was a fairly classless society due to geographical ambiguity and the fluidity of socioeconomic class. The fighting against the Moors wasn’t as organized as one would assume; most of the skirmishes were a result of regular, unorganized male farmers and merchants that fought in their small rural towns. These individual campaigns were largely motivated by desire for capital, in which the municipal militias would loot the Muslim dwellings they defeated. While many military victories were the result of informal rural skirmishes, the King would also order battles, mostly targeting a significant Moorish city, and farmers and merchants would be summoned as warriors to join the cause.

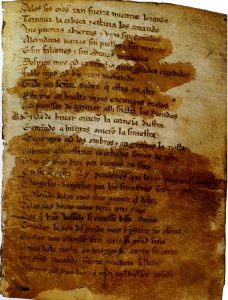

Many scholars debate over the exact date of “El Cantar de Mio Cid” due to the fact that no date was written on the document and different interpretations of the style of writing. Spanish philologist Ramón Menéndez Pidal theorizes that the epic poem was written in around 1307. According to Menéndez Pidal, most authors during this time period would draft these ballads and pieces some 50 years after the death of the hero being discussed so that the story of the hero would be fresh in the minds of the community. Before the official “El Cantar de Mio Cid” was written, Menéndez Pidal says that juglares, public performers of ballads and epics, would create their own various renditions and interpretations of the story, and it wasn’t until 1140 that all the different interpretations of the story of El Cid were compiled into one single narrative with many authors, which was then written and copied by someone who signed his name as Per Abbat in 1307, which is the manuscript referenced today. However, other scholars believe that the poem was developed far later, and the manuscript was drafter earlier. Due to phrases in the poem that reference the kings’ relation to El Cid, which were nonexistent until 1201, and that the manuscript itself was composed in 1207.

The hero of the epic poem himself, El Cid, was born Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar, and grew up in an affluent setting, the court of King Ferdinand I, whose son, Sancho, became King Sancho III and subsequently nominated El Cid to be a military commander. El Cid then led a successful conquest against Zaragoza, a Moorish kingdom, and the Christian kingdoms of Sancho’s brothers. When Sancho passed away in combat, El Cid, having warred against one of Sancho’s brothers who was the heir to the throne, Alfonso VI, was left in a rather uncomfortable situation. To diffuse the tension, he married Alfonso’s niece; unfortunately, after leading an unauthorized military campaign against Toledo, controlled by Moors at the time, Alfonso officially exiled him.

However, El Cid didn’t lay low during his exile. He sought refuge from the same Moors of Zaragoza he had previously fought and partook in fighting on behalf of it against the Christians. While in exile, his exposure to the politics of Iberian Christian-Moorish relations would lay down the foundation for his future military efforts.

In 1086, a band of Almoravids, a dynasty of Muslims from what is now Morocco, invaded Al-Andalus and presented a reinforced threat to the Christian Reconquista. Upon this event, Alfonso VI called back El Cid from exile to ask for aid against the invasion. El Cid’s most famous military campaign, and the theme of “El Cantar de Mio Cid”, was taking back Valencia from the Almoravids. An internal rebellion within the Almoravids that led to the displacement of Valencia’s ruler al-Qādir left Valencia vulnerable to El Cid’s armies, who besieged the city from 1092 until his death in 1099. Shortly after his passing, Valencia was reconquered by the Almoravids, but the legacy and heroic narrative of El Cid resonated throughout the Castilian society, forming the ballad that became “El Cantar de Mio Cid”.

The scribe of the epic poem, signed as Per Abbat, used Old Spanish, or old Castilian in the poem; however, not only do other languages affect the composition of the poem, but there were many other languages with significant prominence during this era. The title itself, “El Cantar de Mio Cid”, may be in Castilian, but the name “El Cid” itself has its roots in Arabic. “Cid” is likely derived from Mozarabic (Romance and Arabic fusion) al-sīd and Arabic sidi or sayyid, all translating to “lord”. Throughout the rest of the Iberian Peninsula, several other languages existed prior to the domination of Castilian and Portuguese that exists today. To the West, in what is now Portugal, Galician-Portuguese was spoken, Leonese was spoken directly to the East of that, Basque was spoken in the Northeastern region of what is now Spain and the Southwestern region of what is now France, Aragonese prevailed to the East of the Basque region, and Catalan was spoken along the Eastern coast of the peninsula, and on top of Mozarabic, Arabic was also spoken in Al-Andalus. “El Cantar de Mio Cid” is written in Castilian, which later spread throughout the peninsula by means of the Reconquista and other inherent interlingual tendencies.

This struggle for control and persistence is not only visible during the Reconquista but across several different eras and regions. In the same manner that the Christians fought to reclaim their identity and belonging for centuries after the Moors invaded, people repressed by invaders and military strength never give up their fight to retain their identity, culture, and prominence. Throughout the world, there are people struggling to maintain their culture in the face of imperialism and oppression. The substratum cultures of the Americas, as an example, fell quickly to the militaristic and assimilating tactics of European colonizers, whether it be the Spanish invaders in Latin America or the British invaders in what is now the United States. Often, people consider the national borders that exist now to separate North America and the Latin America, ignoring the parallels that exist in the experience of substratum indigenous populations across the supercontinent. The Iroquois, Inuit, and the Sioux of North America and the Mapuche, Quechua, and Mayan descendants of Latin America all share a similar history of indigenous existence, oppression, assimilation into superstratum invaders, and struggle for identity in the face of these imperialist and colonist situations. In a similar manner, the Christians who survived the invasion of the Moors attempted to not only retain their culture and identity, but to reclaim the land that was previously theirs and reestablish their existence.

While this may seem like a historical phenomenon, the ramifications of the oppression of superstratum cultures and languages over those that are substratum are seen every day across the world, especially in the United States with the rise of white nationalism and xenophobia. The general lack of respect and sense of superiority that Caucasians feel toward other races is a reflection of more powerful cultures and languages taking priority over others, including the oppression of indigenous tribes and Latinx immigrants, which has been a huge topic of controversy in the US with anti-immigrant rhetoric, talk of building a symbolic and physical wall on the border of the US and Mexican border, and years of hushed oppression of indigenous groups. The situation that happened in the Iberian Peninsula with the Reconquista can serve as an example for humanity of the nature of struggles for existence and how influence of one culture and language to another can affect the dynamics of a region for centuries; this understanding is something we all can learn with regard to the power struggles happening in the world today.