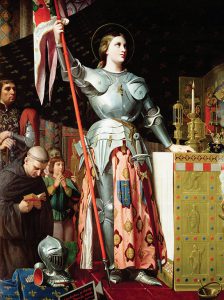

Joan of Arc at the Coronation of Charles VII, by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres in 1854

Joan of Arc at the Coronation of Charles VII, by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres in 1854

Christine de Pizan (1364-1430), a French poet and author of numerous literary works, was one of the greatest writers of the Middle Ages. Ditié de Jehanne d’Arc, a poem commemorating and honoring Joan of Arc and her heroic deeds, was her final piece. This socio-historical introduction seeks to provide context for de Pizan’s literary masterpiece by exploring the Hundred Years’ War up to 1429, the life and deeds of Joan of Arc, and Christine de Pizan’s background as a person and as a writer.

The war between England and France that would become known as the “Hundred Years’ War” began in 1337. The war actually lasted for 116 years, ending in 1453, although there were several truces called over the course of the war. Before this, England and France had been at war on several occasions, creating a long-standing rivalry. English rulers had holdings in Aquitaine, though they were still subject to French authority, creating a complicated and often violent dynamic between the two nations. In July 1337, “the French army… and the Count of Foix’s force… pursued campaigns of harassment and small-scale devastation.” Attacks continued in 1338 and in the spring of 1339, “the French were able to make serious inroads and were now establishing garrisons along the Dordogne and Garonne” (Curry 31). French forces attacked Southampton in October 1338 and raided the English coast in May 1339. The English retaliated with a raid of Le Treport in August, but overall the French won the first stage of the war.

Edward III of England raised an army in 1338 and received authorization from Lewis of Bavaria to act throughout Germany and France as “vicar general of the Empire” (Curry 33). In 1339, Edward and his allies entered the Cambrésis. 45 French villages suffered damage. In 1340, Edward declared himself king of France. He gained support from the Flemish and led a campaign involving their forces to exact revenge for his earlier losses. He could not stop a French advance, however, and “there was further devastation caused by the French towards Cambrai” (Curry 36). The English won support in Gascony and had a major win at sea, though Edward’s following attempt to besiege Tournai was a disaster. This was followed by a truce that lasted nine months.

The French region of Brittany became England’s main focus following the truce because of its attempted split with France. King Edward landed in Brittany in October of 1342 and laid siege to Varnes and sent out raiding parties. The campaign failed because of a lack of reinforcements from England. A truce was called from 1343 to 1346 “to facilitate negotiations under papal authority at Avignon” (Curry 37). The next series of English attacks largely failed, although English forces defeated Charles of Blois. England achieved major victories in French territory. 1346 marked a turning point as English focus turned from the use of allies, such as Ireland, to the use of its own forces to attack the French. English strategy became offensive “for the rest of the century” (Curry 39). A treaty struck in 1360 gave King Edward sovereignty over half of France, indicating that he had won the war.

Charles V of France found loopholes in the treaty of 1360 and exploited them. He claimed “the right to hear appeals as overlord and to the confiscation of English lands in November” (Curry 46). Edward also declared himself king of France again. These events led to the next stage of the war. After a French gain, England fortified its long-abandoned home defenses. English forces attacked the north, while French forces campaigned in the southwest. France regained much of its losses, leaving England in a position that was “perhaps weaker than ever” (Curry 50) in 1377. Brittany became neutral instead of allied with England. Edward II’s descendants’ campaigns were unsuccessful. Since the cost outweighed the benefits, England no longer sent large forces to France. French forces defeated the Flemish townspeople, weakening their alliance with England. A 1389 truce led to a 26-year truce beginning in 1396, ending the second stage of the war.

English king Henry IV took advantage of the French civil war and aided the Armagnacs. King Henry V followed this precedent of aggression and launched an expedition into France in 1415, officially starting the third stage of the Hundred Years’ War. His forces won both a land and a sea battle before moving on to take Normandy, Caen, Alencon, and other major cities. King Henry V’s war aim “was to take and hold Normandy” (Curry 60), which he did. He then expanded his goal to winning the crown. He died in 1422, making English conquest much more difficult to achieve and allowing the French Dauphin Charles to gain support, although French losses allowed the English to advance. These advancements culminated in the siege of Orleans in October 1428.

English gains “came to an end when the French, inspired by Joan of Arc, raised the siege of Orleans in May 1429.” The French victory at Orleans, followed by several others, paved the way for the Dauphin to be crowned as King Charles VII in July of 1429. The English, however, retained control of Paris and its other holdings (Curry 63-64).

The heroine of Orleans, Joan of Arc was born c. 1412 in Domrémy, Bar, France, to a tenant farmer. She felt that she was guided by the voices of various saints, such as St. Michael the archangel, St. Catherine of Alexandria, and St. Margaret of Antioch. She had many strong characteristics, especially “mental and spiritual courage, as well as a robust common sense.” Female visionaries were a “notable feature” of the time—many pieces were written about female biblical figures such as Esther, Judith, and Deborah, as mentioned in Ditié, for example—and Joan of Arc shared many qualities with them, namely “extreme personal piety, a claim to direct communication with the saints, and a consequent reliance upon individual experience of God’s presence beyond the ministrations of the priesthood and the confines of the institutional church” (Lanhers 1).

Joan’s God-given mission was to ensure that the Dauphin Charles would be crowned king. Since Reims, the traditional place for the coronation of French kings, was well within England’s control, the Dauphin’s legitimacy could be challenged because he had not yet been crowned king. Domrémy was on the border between English and French control, so Joan “traveled in May 1428 from Domrémy to Vaucouleurs, the nearest stronghold still loyal to the Dauphin, where she asked the captain of the garrison, Robert de Baudricourt, for permission to join the Dauphin. He did not take the 16-year-old and her visions seriously, and she returned home” (Lanhers 2). When she returned in January 1429, she was able to persuade the captain that she was “neither a witch nor feebleminded” and was granted permission to see the Dauphin, who tested her by hiding himself in the crowd. She quickly pointed him out and told him her mission: “to go to battle against the English and… have him crowned at Reims.” After much further testing and questioning, Joan’s motives were proved true.

Joan was given troops and a standard and banner. She claimed that a sword for her would be found in the church of Sainte-Catherine-de-Fierbois, and she was correct. On May 4, 1429, she sprang into action, joining an engagement between French and English forces. She roused the French fighters and they took the fort. Two days later, she took another. On May 7, Joan was wounded but continued fighting for another fort, inspiring her forces to continue until the English surrendered the fort.

At Joan’s urging, the Dauphin agreed to be crowned once the English lost more territory and control. With the Duc d’Alençon, Joan took a town and an important bridge before accepting the surrender of the castle of Beaugency. The French and English armies met at Patay on June 18, 1429. The English army was utterly defeated. After much convincing, Joan persuaded the Dauphin to be crowned king, which finally took place on July 17, 1429 (Lanhers 4).

While historical accounts offer a straightforward view of Joan’s life and actions, literature “offers… the image of Joan of Arc in her own time” (Fraioli 811). Literature conveys not just what she did, but the meaning and significance of her actions. Associated with biblical figures and prophecy, Joan of Arc was a culturally significant figure and continues to be one today. Whether real or exaggerated, her links “with both the past (the biblical heroines) and the future (her implied connection with the Last Days) may have spelled the difference between her becoming ‘just another visionary’ and her being accepted as the restorer of France” (Fraioli 812). Three treatises written about Joan of Arc compared her to biblical heroines such as Deborah, Judith, and Esther. Christine de Pizan did the same in Ditié de Jehanne d’Arc. De Pizan “aligns Joan of Arc firmly with this tradition, declaring in the last line of the stanza that the Maid’s accomplishments surpass even the accomplishments of these illustrious women.” While the writers of the other treatises revered Joan of Arc for her piety and skills, de Pizan argued that “it is precisely the Maid’s triumph in a masculine world that makes her so worthy of praise” (Fraioli 815).

Christine de Pizan’s Ditié de Jehanne d’Arc was the “first non-anonymous writing in French to honor Joan during the heroine’s brief lifetime” (Margolis 81). De Pizan, born in 1364 in Venice, Italy, was one of the greatest and most prolific poets and authors of the Middle Ages. Her father served in Charles V’s court as an astrologer, so she was educated as a child. She married Estienne de Castel when she was fifteen and was widowed at twenty-five. After her husband’s death, she “took up writing in order to support herself and her three young children.” Her writing quickly brought her fame and her patrons included “Louis I, duke of Orléans; the duke of Berry; Philip II the Bold of Burgundy; Queen Isabella of Bavaria; and, in England, the 4th earl of Salisbury” (Britannica 1). She wrote many feminist pieces, such as The Book of the City of Ladies and Book of Three Virtues in 1405, in which she celebrated women who defied gender norms and displayed heroism and virtue. She also analyzed women’s roles in medieval society. Ditié de Jehanne d’Arc was her last known work and is widely acclaimed as her best.

Ditié contains 61 stanzas, beginning with de Pizan’s expression of joy at Joan of Arc’s success and ending with a plea for any cities that reject the Dauphin to accept his rule and become his subjects peacefully, as Joan wishes. I have selected stanzas 27-36 to analyze linguistically. In these stanzas, Christine de Pizan describes Joan’s holiness, her faith, and her strength.