About eleven miles outside of Rome just off the Via Appia once stood the Latin city of Aricia 1. It was here that the goddess was worshipped as Diana Nemorensis, or Diana of the grove. The sanctuary at Aricia, a place of worship since the archaic period, was set in the middle of a dense woodland refuge with gorgeous views of the lake below 2. Lake Nemi, once called the “mirror of Diana” or speculum Dianae by the Romans because it reflected the moon so clearly, nourished the surrounding wildlife and provided hunters with a bountiful supply of game 3. It is no wonder that this grove in the crater of an extinct volcano with its scenic landscape, celestial-reflecting lake, and haven for wildlife was chosen to worship Diana Nemorensis.

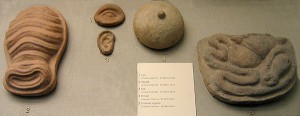

Not only was Aricia a haven for animals, but it also served as a refuge for pilgrims traveling to and from Rome in need of healing 4. Dedicatory inscriptions have been found at the sanctuary placing some of the early Roman emperors (Tiberius, Claudius, Hadrian, and Trajan) on Diana Nemorensis’s list of worshippers 5. Aside from these inscriptions, terracotta votives in the shapes of human body parts and animals have been found at the sanctuary 6. Curiously, some of the votives are in the shape of uteri and other internal organs suggesting that by leaving a votive of an ailing body part at the sanctuary, Diana Nemorensis would heal it.

However, the cult of Diana Nemorensis was specifically one of hunting because “the hunt itself was considered a sacred rite to Diana” 7. The cult provided her worshippers with the knowledge and skills needed to be a successful hunter, which included an acute awareness of animals themselves, both wild and domestic 8. To be a good hunter was to have respect and an understanding of nature itself.

Unique to this hunting cult was its priestly position of the rex nemorensis, or king of the wood. This head priest of the cult of Diana at Aricia was extremely significant because of the ritual associated with his ascension. Any time the sanctuary authorities deemed the cult was in need of a new priest king, a challenger was chosen to hunt down and kill him in order to take his place as rex nemorensis 9. According to C.M.C. Green, “the ritual of the rex nemorensis enacts an anxiety of the early hunter-warrior: when does the hunted become the hunter, and what is the meaning of the death of the one hunted?”10. This ongoing ritual murder was crucial to the identity of Diana Nemorensis. The Roman poet Ovid (43 BCE – 17/18 CE) was aware of this ritual and referred to Aricia in his Ars Amatoria as “the kingdom obtained through swords by a hurtful hand.”11. Ovid’s telling of the story of Actaeon in the Metamorphoses echoes this transition from hunter to hunted.

The Story of Actaeon is one of the more gruesome tales in Ovid’s Metamorphoses and it begins in a setting reminiscent of the sanctuary at Aricia:

“There was a valley there, all dark and shaded, with pine and cypress, sacred to Diana, Gargaphie, its name was, and it held deep in its inner shade a secret grotto made by no art, unless you think of Nature as being an artist. Out of rock and tufa she had formed an archway, where the shining water made slender watery sound, and soon subsided into a pool, and grassy banks around it. The goddess of the woods, when tired from hunting, came here to bathe her limbs in the cool crystal.” 12

The young Actaeon, taking a break from his hunt at high noon, stumbled into this sacred grove and happened upon Diana and her nymphs bathing in the cool waters. The nymphs tried to cover up their goddess, but she was too tall and Actaeon caught a glimpse of her nude body. By viewing Diana’s naked body without an invitation, Actaeon threatened her chastity, the virgin goddess’s most prized virtue. Diana, who would have shot him with her bow and arrows if she had not left them on shore, was left vulnerable. Outraged by this mortal man’s violation of her maidenhood, Diana cursed him with a splash of water on his head. From this spot on top of Actaeon’s head, a set of stag horns began to grow. Then, slowly, the rest of his body began to transform into that of a deer and “the hunter’s heart was fearful” 13. While trying to decide whether to hide in the woods or run back to the palace, his own hunting hounds caught his scent. However, it was not the hunter Actaeon’s scent the dogs picked up, but the scent of a stag. His dogs, well trained by Actaeon himself, did not recognize their master, and since Actaeon lost the ability to speak during his transformation, he was unable to warn them, and so he fled: “Actaeon, once pursuer over this very ground, is now pursued, fleeing his old companions” 14. When the dogs caught up to him, they tore him apart, “their prey, not master, no master whom they know, only a deer” 15.

This story of Actaeon, the hunter who became hunted by his own dogs, is visually expressed on a sarcophagus in the Louvre. The Roman craftsman made the story of Actaeon recognizable by leaving his transformation incomplete. As stated in Living with Myths, had Actaeon been depicted as a stag, the scene would have been indistinguishable from a regular hunting scene, and the use of the Actaeon myth on this sarcophagus was to express the grief and sympathy for a sudden death 16. So, instead, Actaeon is depicted as human except for the horns sprouting from his forehead to suggest his transformation into a stag. The scenes are shown out of order; the death and transformation of Actaeon comes before the scene where he watches the nude goddess bathe. The scene of Actaeon’s death is emphasized because the sarcophagus design is a metaphor for undeserved and untimely death. Then, what follows the undeserved death is a peaceful resting place suggested by the idyllic scene of Diana in the woods, which is attempting to give the grieving some peace.

- C.M.C. Green, Roman Religion and the Cult of Diana at Aricia (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 3. ↵

- Green, Roman Religion and the Cult of Diana at Aricia, 10. ↵

- Green, Roman Religion and the Cult of Diana at Aricia, 6. ↵

- Green, Roman Religion and the Cult of Diana at Aricia, 15. ↵

- Green, Roman Religion and the Cult of Diana at Aricia, 280. ↵

- Green, Roman Religion and the Cult of Diana at Aricia, 18. ↵

- Green, Roman Religion and the Cult of Diana at Aricia, 123. ↵

- Green, Roman Religion and the Cult of Diana at Aricia, 125. ↵

- Green, Roman Religion and the Cult of Diana at Aricia, 154-156. ↵

- Green, Roman Religion and the Cult of Diana at Aricia, 11. ↵

- Green, Roman Religion and the Cult of Diana at Aricia, 28. ↵

- Ovid, Metamorphoses, Translated by Rolfe Humphries (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1983), 61-62. ↵

- Ovid, Metamorphoses, 63. ↵

- Ovid, Metamorphoses, 63. ↵

- Ovid, Metamorphoses, 63. ↵

- Paul Zanker and Bjorn C. Ewald, Living with Myths: The Imagery of Roman Sarcophagi, Translated by Julia Slater (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 295-296. ↵