As previously mentioned, the Romans had accepted Diana as twin sister of Apollo and daughter of Latona by the fourth century BCE 1. When Augustus became the first Roman emperor in 27 BCE, he adopted this holy family to visually represent his own in an attempt to solidify his position as princeps after the death of Julius Caesar, his great uncle. Augustus took on the attributes of Apollo and his sister Octavia took on the attributes of Diana 2. This assimilation not only allowed Augustus to claim relations to these deities, but it associated him with the loved mythical brother and sister, Apollo and Diana 3.

This connection to Apollo, Diana, and Latona was not arbitrary. Not only was Diana an important figure representing political and military authority at this time, but the emperor Augustus had deep roots in the cult of Aricia. Both his mother and his maternal grandfather were from this Latin city 4. Julia Minor, the sister of Julius Caesar, married an Arician and they bore Atia Balba Caesonia, the mother of Augustus. However, Aricia’s association with the ritual of the rex nemorensis was a serious issue for the new emperor who had personal ties to the cult.

Julius Caesar’s brutal assassination in 44 BCE set into motion a cycle of successors killing their predecessors that closely mirrored the murder ritual of the rex nemorensis. Julius Caesar’s assassination, as well as the death of Pompey the Great and the conflict between Antony and Augustus, was henceforth associated not only with the rex nemorensis, but also with Diana’s sanctuary at Aricia 5.

“Caesar’s assassination had already guaranteed that the rituals of the sanctuary, and particularly those of Diana’s rex nemorensis, would now be irrevocably elevated to the level of an ambiguous and dangerous religious commentary on autocratic power.” 6

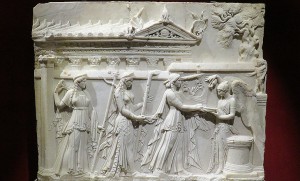

The ritual of the rex nemorensis was a direct threat to Augustus who risked the same fate as his predecessor. Not only did Augustus inherit Caesar’s throne, but he was also heir to Caesar’s enemies 7. However, simply cutting his ties with the cult at Aricia was not possible nor was it advised. In order to keep his connection to Aricia without being directly associated with the rex nemorensis, Augustus adopted the sun god Apollo as his patron deity. Diana, however, did not disappear in the shadow of her brother. Her sacred cypress trees, though muted in the background, are present in the Gardenscape at the Villa of Livia. Augustus even gave her equal rank on his Prima Porta breastplate. Apollo is shown on the left riding a griffin while Diana is shown on the right riding a stag.

Prior to the age of Augustus, Apollo was not taken very seriously as a god while Diana was a much more important figure in Roman religion and politics. Apollo only became significant when Augustus adopted him. The authors of An Exciting Provocation: John F Miller’s Apollo, Augustus, and the Poets insist that Diana should be recognized as an important part of Augustus’s Apolline program and ask the following question of her 8:

“More particularly, since Diana’s cult appears to be much better established in Republican Rome, and since her own versatility begins to be celebrated before that of her brother, should we think of her not only as Apollo’s companion in a role that she would continue to play, but as a late-Republican model for the role that he, too, would eventually assume?” 9

The answer is yes, but it becomes even more complicated when looking at Diana’s transitory nature. Not only did Diana serve as a vehicle to transition Apollo into his new role as representative of Augustus, but she also aided Augustus in his transition to emperor, and was therefore part of the Roman state’s transition from Republic to Empire.

- C.M.C. Green, Roman Religion and the Cult of Diana at Aricia (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 84. ↵

- Green, Roman Religion and the Cult of Diana at Aricia, 84. ↵

- Green, Roman Religion and the Cult of Diana at Aricia, 38-40. ↵

- Green, Roman Religion and the Cult of Diana at Aricia, 27. ↵

- Green, Roman Religion and the Cult of Diana at Aricia, 28-29, 39. ↵

- Green, Roman Religion and the Cult of Diana at Aricia, 32. ↵

- Green, Roman Religion and the Cult of Diana at Aricia, 32-34. ↵

- Bettina Bergmann and others, “An Exciting Provocation: John F. Miller’s Apollo, Augustus, and the Poets,” The Journal of the Vergilian Society 58 (2012): 10. ↵

- Bergmann and others, “An Exciting Provocation: John F. Miller’s Apollo, Augustus, and the Poets,” 11. ↵